1969-70. After more than eight years in the Cuban prison system, Emi Rivero still had not consented to the regime’s proposal that he relinquish his identity as a political detainee.

In 1969 Emi was abruptly transferred from La Cabaña fortress to the Castillo del Príncipe, another Havana prison, where he spent just a few weeks before being transferred again to Guanajay prison, some 50 miles outside Havana.

Not only did the dispute over uniforms remain. A more sensitive deprivation was in store. At Guanajay the guards confiscated his personal possessions, including his books.

Despite his resolve not to show rudeness to guards whatever they did to him, Emi went into a fury over the seizure of his books. He raised his voice to his captors and yelled: “The only way to coerce me is for Fidel Castro to come here and suck my prick!”

Screaming like an inmate of Bedlam, he added: “If snitches are listening, you can repeat what I say to your friends in the central administration!”

To talk that way in the depths of Castro’s prisons was not bravado. It was insanity. The books were returned. Even so, Emi regretted his loss of control.

{Emi’s recollections}

Though my section in Guanajay prison was not having visits that day, the guard called my name and said I should be prepared to leave the cell “correctly dressed.” I assumed my family had managed to get an extra visit.

As I looked around for one of my relatives, the guard told me to follow him. We went through the hall to the prison’s entrance. A Security officer was waiting for me. He signed a paper and signaled me into a car where two guards waited.

The Oldsmobile took off for Havana in a great hurry; the speedometer showed between 160 and 180 kilometers per hour. The driver was quite good.

We arrived at State Security headquarters. I was led through stairwells and corridors to an upper floor. An officer came out of a tiny reception room and told me I was about to see Dr. Guillermo Alonso Pujol.

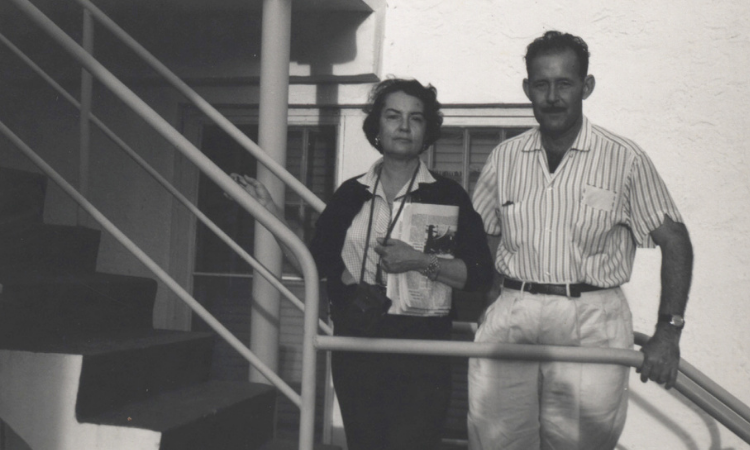

I immediately recognized the man who had served as Cuba’s vice president under Carlos Prío. Now living in Venezuela, he had kept up a strong interest in Cuban matters and was in frequent contact with my parents, whose friend he had remained.

“For almost two years I have been working for your freedom,” Dr. Pujol said. “Your father is gravely ill. I beg of you: Do all in your power so that this effort of mine on your behalf will bear fruit. Don’t make me fail.”

“I am being asked to discuss things I know nothing about, or things I cannot talk about,” I replied. “And they are asking me to wear a common prisoner’s uniform, which is something I can’t accept.”

The Security officer who had been watching our conversation intervened.

“You must wear the uniform the Ministry has chosen for you,” the officer said. “Presently you are in a state of rebellion and we will not consider freeing you unless you change your attitude. As to your activities, we know all about you. There are just a few details that you must tell us. If you fulfill those two conditions, we will consider releasing you.”

Dr. Pujol looked at me and said: “I have presented your case at the highest levels of the Cuban government. The persons with whom I have spoken want to be certain that you are not going to engage in activities against the state if you are freed.”

I answered: “My only interest is to go back to my family and reconstruct my life. As to politics, the Cuban case is over for me.”

“Would you be willing to say that in writing?” Dr. Pujol asked.

“I have no objections.”

As I wrote the letter I told Dr. Pujol of my doubts that State Security would be convinced by it. They would insist on my giving information, and as a consequence we would have no deal.

“What importance do you attribute to talking about things that happened nine years ago?” Dr. Pujol asked. “That belongs to history. Do not jeopardize the opportunity I have of giving you back to your parents!”

“Apparently these gentlemen want to turn me into an informer, and that is something I don’t accept.”

The officer again interjected. “No one is trying to make you an informer!” he insisted.

The meeting ended in a stalemate.

* * *

In trying to secure his release, Emi’s parents were working parallel to the CIA whose main interest was to protect their intelligence nets from being disclosed. American officials were purchasing the release of their agents from Cuba with hard cash.

From allusions in his mother’s letters, Emi understood that his case was a subject of negotiation between the CIA and Cuban authorities. But he had no idea that CIA negotiators were displeased with him for refusing to take an “easy” way out.

When CIA officials talked to Emi’s mother about their failure to make a deal in his case, they were full of rancor. “Your son wants to stay in prison!” they told her.

“No, that’s not true,” la vieja said firmly. “What he wants is not to be a traitor.”

The complete book is being published by Pureplay Press. The book, including all material therein, is copyright © 2020 by David Landau.

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from now through early October, the Impunity Observer will publish excerpts from Landau’s book

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.