When one country sends an ambassador to another, it is first and last a recognition of sovereignty.

So what can you say about an American ambassador who openly meddles in the affairs of a host country, then goes before the press to declare: “In the list of my concerns, sovereignty comes last”?

You have to wonder how Obama or his envoy would react if some bigger bully were to come along and play with America’s sovereignty.

Admittedly, the idea is strange. But with our reduced military and bloated external debt, we might easily be subject to the whims of others.

Vladimir Putin has already used the editorial page of the New York Times to give a lecture to Americans.

What if a foreign ambassador were to go further and weigh in on the matter of a Supreme Court nominee?

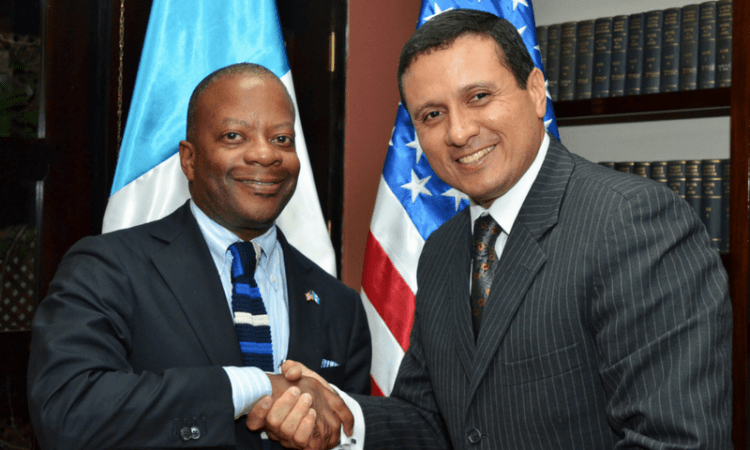

That’s precisely what US Ambassador Todd Robinson has done in Guatemala.

Robinson and his staff recently conducted a no-holds-barred campaign to secure the re-election of a favored justice to Guatemala’s highest court. The embassy pulled on every string to get the result it wanted.

On April 19 a member of congress, Fernando Linares, wrote Secretary of State Kerry and informed him that a US embassy official had been present in congress, “supervising the vote.”

The effect, according to Linares, was to stop debate and pass the judge almost by acclaim. Linares told Kerry that his own right to take part in the debate had been violated.

The congressman ended his letter to Kerry by saying of Robinson: “Please replace him.”

That letter put Linares in the embassy’s cross-hairs. Hardly anyone in the political class had dared object openly to the ambassador’s actions. On Facebook, a commenter said of Linares: “At last, somebody with balls.”

Two Catholic officials have entered this fray. The pope’s ambassador, or nuncio, issued a statement that warned about diplomatic interference in general. Guatemala’s archbishop then clarified that the nuncio’s warning referred to the US.

Historically, church officials have mixed in politics to help other parties resolve their disputes. At least that’s the ostensible goal.

But not, perhaps, since the days of Caligula has a lay diplomat gone so far out of his way to offend a papal emissary. Robinson answered by saying that “the nuncio’s words don’t matter to me.”

Obama’s embassy in Guatemala is chock full of wisdom about other people’s business. The recently-issued State Department report on human rights for 2015 contains this statement in proper jargon:

“Indigenous representatives stated that a number of regional development projects failed to consult meaningfully with local communities and disproportionately benefited corporations, government officials, and their associates while posing risks to indigenous lands and cultures.”

Hidro Salá, a hydroelectric company whose project in western Guatemala has now been held up for six years, responded in a statement by Héctor Herrera, the company’s community liaison:

“Consistent with our obligation and good business practice, we completed all the required studies and consulted with local communities, who overwhelmingly supported our project.”

The next part of Herrera’s statement gives the full context of the situation, which the human-rights report conveniently ignores.

“Subsequently, the local population came under the control of violent armed groups opposed to the project, preventing them from freely expressing their will. The government has abandoned the area, depriving the local population, including our company, of the protection of law.”

It is hardly conceivable that the US embassy did not know these facts.

In August 2014, two reporters had visited the region and had spoken with people who said they wanted the blocked project to go forward. At the time, The Daily Caller published an account of the dispute.

The reporters arranged to get a comment from the militia. When they showed up for the interview, about 20 of the militia’s tough guys physically threatened them. One of the journalists managed to record the incident. The high points can be heard in a radio report, later broadcast in California.

When you compare the statements in the US human-rights report with the statements of the militia, you see they are a 100-percent match.

Under the Obama administration — most crucially under Hillary Clinton, who worked through Guatemala’s attorney general — the US has energetically supported the spread of these militias, which UN officials and others have called “human-rights groups.”

The magistrate whom Ambassador Robinson worked so hard to keep on the country’s high court is a reliable supporter of those militias. That judge may now be counted on to jiggle the country’s laws in the militias’ favor.

So there you have the kind of policy that Ambassador Robinson prefers over considerations of sovereignty. It brings to mind a quip well known to Latin Americans.

Why does the US never have a coup d’état? Because it has no US embassy.

This article first appeared in the Daily Caller.

Steve Hecht contributed to this article.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.

One comment