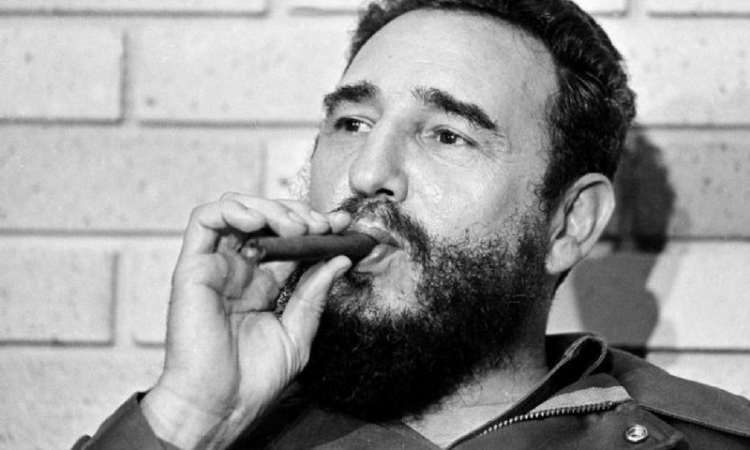

Now that Fidel Castro has finally done the one thing we all must do, he’s getting the same kinds of notices he got before – like a long-running Broadway show that closes to rave reviews.

The New York Times exalted him in these terms: “Mr. Castro brought the Cold War to the Western Hemisphere, bedeviled 11 American presidents and briefly pushed the world to the brink of nuclear war.”

The Times and other media, in their collective farewell to Castro, have created yet another tourist brochure for the country called history. The basic truth about Fidel is more simple and apparently unspeakable: the man was a bottomless pit.

A decade or more ago, while still in command of Cuba, Fidel attended a reception at the U.S. Interests Section in Havana. The chief of the section – the U.S. ambassador in all but name – introduced Fidel to various visitors from the State Department and described one of them as being “in charge of Cuban affairs.”

“No!” Fidel said with surprising vehemence. “I am in charge of Cuban affairs!”

No humor or wit attached to Fidel’s statement. It was a cry of desperation that had come roaring into the room from out of nowhere.

Sometime later, that same virtual ambassador told me the story. Fidel was a man who wanted, first and last, to be the only focus of attention. At the heart of his political vocation was that single central need.

In his rise to power, Fidel was notably free of morals and ideologies. Once in power, he repeatedly purged the Cuban Communist Party with the evident goal of becoming – what else? – the only real communist in Cuba.

Internationally, he hit a wall when JFK bested Khrushchev in the missile crisis. Probably the worst day of Castro’s life was the day the Soviets agreed to remove their nuclear missiles from Cuba.

Castro had to learn of that decision not from his own allies, the Soviets, but from news reports. He suddenly went from being at the center of the world to haunting its outermost periphery.

The episode seems to have given Fidel a psychic break. To recuperate, he abandoned his capital city and sought comfort in the hills of eastern Cuba – from where, five years earlier, he had mounted his offensive against Batista’s regime.

A crisis perhaps even deeper awaited Fidel the following year, with Kennedy’s assassination. On that very day of November 22, 1963, U.S. broadcasters were announcing that the suspected shooter was an admirer of Castro’s regime.

Those news reports, or so a U.S. intelligence official later said, were enough to drive Castro into hiding – from fear the U.S. would blame him for the president’s death and would come after him in earnest this time.

But then, a year later, Castro was once again on top of the world when the Soviets got rid of Khrushchev. Of the three protagonists in the missile crisis, Castro was the only one left standing – and he would hold power for an unthinkable 43 more years.

How did he achieve that longevity? For one thing, his intelligence and police services were unbeatable. They were buttressed by his unparalleled gift for political theater.

But the most vital of Fidel’s assets was the cruel quirk of history that gives a lucky edge to tyrants.

Brecht once observed, with more wit than Castro ever dreamed of, that if a communist regime could not get the approval of its people, it could just get another people.

That’s precisely what’s happened since 1959 as Cubans have fled from their homeland in the millions – many preferring to take their chances with the sharks, rather than live another day under Fidel’s suffocating presence.

And there’s the supreme benefit of Castro’s demise. Without a leader consuming all their oxygen, the Cuban people can begin to breathe again for the first time in 58 years.

This article first appeared in the New English Review.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.