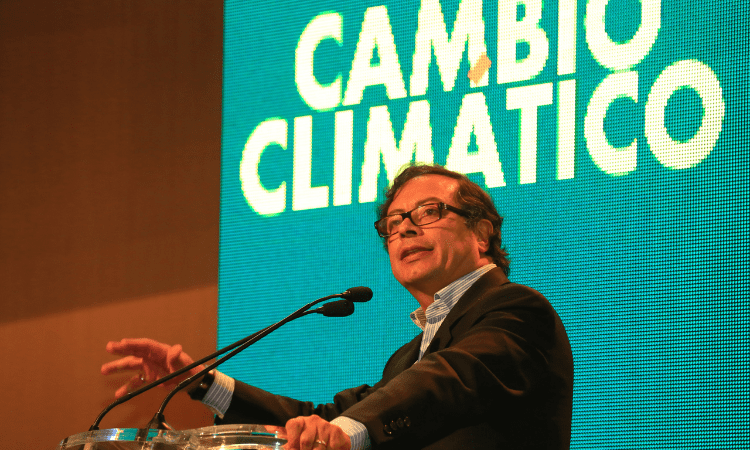

On June 19, 2022, Gustavo Petro won the Colombian presidential election, becoming the country’s first overtly leftist president. The subsequent fall in Colombian financial markets reflects widespread concerns about Petro’s pledge to enact deep economic and social reforms.

On June 21, the stock market’s opening day after his victory, the Petro effect was unmistakable. The MSCI Colcap Index for the Colombian stock market dropped by 5 percent. The stocks of the state-run oil company Ecopetrol fell by 11.2 percent, and the national currency, the peso, depreciated against the dollar by 5 percent. Similarly, the Colombian risk premium, which was 964 points before the election, is now 1,197 points. That translates to 12 percent on the nation’s sovereign debt.

Petro’s political coalition was the Historic Pact, a group of political movements promoting 21st-century socialism and a hodgepodge of policies backed by the woke left. Petro intends to increase public spending, taxes, and import duties. He has also announced land redistribution, the renegotiation of bilateral trade agreements, and a gradual reduction in hydrocarbon and mining industries.

Petro’s policy plan emphasizes “social and environmental justice.” Investors and businessmen have reason to fear this will cause macroeconomic instability. Actions speak louder than words, and capital allocators have already shown they perceive Colombia to be a higher risk jurisdiction with Petro at the helm.

Petro Does Not Have Free Rein

Petro did not score an overwhelming victory. He got 50.4 percent of the votes versus the 47.3 percent for his opponent, businessman Rodolfo Hernández. Moreover, absenteeism surpassed 50 percent of the voter roll.

On August 7, Petro will take office with a divided Congress, where his political party does not have a majority in either the House or in the Senate. Therefore, passing the series of reforms to implement his ambitious plan is not a given.

According to his statements, Petro argues that the state—not markets—should rule the Colombian economy. He has made no secret of his desire to increase state intervention in the productive sectors of the economy and raise taxes. In 2020, however, Colombians opposed tax increases in nationwide protests, forcing the former administration to overturn them.

Tax Reform That Chases Away Its Base

Petro’s policy plan includes a tax reform to raise revenue collection by about 4 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), which means 50 billion Colombian pesos (roughly US$12 billion). Petro will allocate half of that amount to reducing the fiscal deficit and the other half to increasing public spending.

The incoming president has promised that this reform will not affect citizens in general. He has said it will target the “unproductive” assets of the 4,000 wealthiest people in Colombia.

However, economist Ricardo Bonilla, the author of the economic program presented by Petro, has made a different claim. Bonilla has announced that the tax reform will impose higher rates on those with assets of more than 1 billion pesos ($220,000). In addition, the incoming administration will assess the feasibility of extending the value-added tax to currently exempt products and increasing the income tax to those earning over 100 million pesos annually ($22,000).

According to the Financial Times, the real-estate sector in Miami has rebounded due to the large number of queries from Colombian citizens after Petro won the election. They see Miami as an ideal location, not only to protect their assets but also for emigration. Colombians are following the trend of Chileans and Peruvians after the electoral victories of Gabriel Boric and Pedro Castillo, respectively.

How to Jam Up an Economy

Petro favors expanding the money supply to artificially stimulate the economy, even though the Colombian central bank is purportedly independent of politics. By doing so, Petro would follow the Argentine path of playing with modern monetary theory. With 14.7 percent depreciation, the Argentine peso was the world’s second most depreciated currency in 2021.

That is not all. Petro’s plans for the hydrocarbon and mining sectors have raised alarm bells for investors. Petro wants to accelerate the transition to the so-called green economy by rejecting energy projects that are in the exploration phase and reducing current extraction. He has announced the cancellation of fracking and open-pit mining projects.

These pledges come at a hefty price. Revenues generated by the hydrocarbon industry represent 3.3 percent of the national GDP, while mining represents 2 percent.

The announcement that socialist-leaning economist José Antonio Ocampo will be Petro’s economic minister, a position he has already occupied without delivering positive outcomes, has far from calmed financial markets. After Ocampo’s appointment, the Colombian peso continued its depreciation relative to the US dollar—a trend that sharpened after Petro’s victory. Since the first round of the presidential election, the depreciation has been 13 percent.

Algunos hechos sobre nuestro nuevo ministro de Hacienda, @JoseA_Ocampo, que pocos se han atrevido a mencionar. pic.twitter.com/hBkKx9QlLg

— Julio César Iglesias (@IglesiasJulio87) July 3, 2022

A Marxist Terrorist: What Could Go Wrong?

Petro made himself known in the 1980s as a member of the now-dismantled M19 guerrillas. A decade later, after a period underground, Petro started participating in politics as a member of the House and the Senate for several terms.

In 2011, Petro became mayor of Bogotá, the capital city. His administration was full of mismanagement and alleged corruption that led to the Colombian attorney general dismissing him from office. However, based on a technicality, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ordered the Colombian government to reinstate him, which it did.

When Petro finished his term with the Bogotá municipality, public disapproval was 68 percent. His poor performance did not impede Petro from turning into the Colombian left’s caudillo and becoming the Colombian president in 2022. Petro did, however, soften his rhetoric.

Colombia was the chief South American country that resisted the first wave of 21st-century socialism in the 2000s. Nevertheless, former President Juan Manuel Santos undermined the country’s institutionality when he disregarded the democratic will of Colombian citizens and approved an amnesty agreement with the FARC guerrillas. Although most citizens voted against this, Santos granted privileges and even legislative seats to the terrorists. Santos had backing from the Obama-Biden administration.

According to a Yanhaas survey of public opinion and voter intent nationwide, before the runoff, 54 percent of Colombians feared the country’s political institutions were not strong enough to resist the potential attack of Bolivarian socialism. As stated by William Jackson, an emerging-markets economist at Capital Economics, Petro’s victory will likely drive investments out and provoke a massive sale of assets in the country’s financial markets.

With Petro’s leadership, Colombia joins the latest wave of the 21st century starring Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Chile, and Honduras. Petro’s paradigm shift envisages a step back from Colombia’s economic achievements in recent decades. Petro’s pledges weaken the private sector and dissuade investment. The numbers speak for themselves.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.