Key Findings:

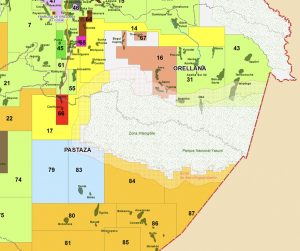

- On August 20, 59 percent of Ecuadorians voted in favor of halting oil extraction operations in block 43 of the Yasuní National Park (YNP). It is located in the Orellana and Pastaza provinces in the Amazon region.

- The YNP is one of the most biodiverse zones in the world, according to scientific journal PLOS One. It is home to at least 1,130 tree species, 81 bat species, and 593 bird species. Further, three indigenous nationalities live there: the Kichwa, the Shuar, and the Waorani.

- Apart from leaving thousands of citizens without employment, the ban on extraction in this portion of YNP could set a negative precedent for investment elsewhere in the country. “Billions of dollars in investment will go to waste after companies cease to operate in block 43,” according to Walter Spurrier, vice president of Esquel, a development NGO.

Overview

In the first round of this year’s presidential election, on August 20, 2023 (called early by President Guillermo Lasso), Ecuador simultaneously held a referendum regarding oil drilling in the Yasuní National Park (YNP)—one of the most biodiverse areas per square meter in the world. Proposed by local environmentalist nonprofit Yasunidos, the referendum for halting oil drilling in block 43 of the YNP won with 59 percent of the votes.

Ecuador’s Constitution, in Article 105, allows citizens and civil-society organizations to propose referendums on “relevant topics” as long as they do not entail constitutional amendments. Yasunidos worked for 10 years before the Constitutional Court and the electoral authority approved their referendum. This is the first organization in the country’s history that has successfully triggered a nationwide referendum.

On May 9, five out of nine judges of the Constitutional Court approved the referendum. It read: “Do you agree with the Ecuadorian government leaving the oil in the block Ishpingo, Tambococha, Tiputini (ITT)—block 43—indefinitely underground? Yes or no.”

The YNP is located in the provinces of Pastaza and Orellana, in the Amazon region. Orellana is home to block 43, where oil drilling will halt next year. Notably, Orellana is one of two provinces where the “no” option won in the referendum, with 58 percent of the votes. The electoral results in Orellana sparked multiple discussions regarding whether the entire country should have a voice over the provinces with the biggest oil-extraction impact.

Those who would feel the greatest economic loss predictably wanted to continue extraction. Economic analyst and columnist for Vistazo Magazine Alberto Acosta Burneo explains that Orellana’s inhabitants voted to continue oil extraction in block 43 because they have witnessed firsthand the direct economic and development benefits from extraction companies operating, consuming, and investing in that area.

On the other hand, founder of environmentalist NGO Yasuní Resists Nahiara Morán asserts that people from Orellana have to get over oil extraction: “There is life after extraction, but it is hard to see it when all people have ever experienced is extraction.”

YNP in the Cross Hairs

A one-million-hectare territory, the YNP has the country’s largest oil reserves underground: around 1.67 billion barrels. Local and foreign companies started oil extraction operations in block 43 in 2016. At present, block 43 has 12 oil platforms and 230 wells, which are producing 57,000 barrels of oil per day.

Regarding its environmental importance, the YNP is one of the most biodiverse areas per square meter in the world,” according to scientific journal PLOS One. The YNP is also home to 1,130 tree species, 81 bat species, and 593 bird species.

In addition to being an extremely biodiverse area, the Ecuadorian Amazon (one of the country’s four regions) is home to 11 indigenous nationalities: Kichwa, Shuar, Achuar, Sapara, Shiwiar, Andwa, Quijos, Siona, Siekopai, Ai´Cofán, and Waorani. The latter includes two uncontacted sub-groups named Tagaeri and Taromenane. Three of these nationalities live within the YNP.

The Tagaeri and Taromenane are living in voluntary isolation from the rest of society in a protected area called the “Tagaeri Taromenane Intangible Zone.” Article 407 of the Constitution forbids extractive activities in the intangible zone. However, there are eight oil-extraction blocks that are just outside the intangible territory in the so-called buffer zone.

The Broader Impact on Ecuadorians

“Ecuador is a country that depends on oil extraction. Oil extraction revenues pay for new state-built infrastructure such as roads and hospitals,” explains Quito-based economics professor Luis Espinosa Goded. Lauro Papa, spokesman of a Kichwa community in Tiputini, contends that oil exploitation has provided them with development and education.

Espinosa explains that there is a “widespread misconception” of how halting the oil extraction in block 43 will affect citizens and the Ecuadorian economy. While the discussion in traditional media outlets has focused on the income that the state will stop receiving, Espinosa points out that “the real problem is the thousands of people that will be out of a job for halting the oil extraction operations in block 43.”

Due to their complexity and need for highly specialized workers, extractive industries have proven to be important in terms of job opportunities for Ecuadorians. For example, the mining sector helped create 132,736 direct and indirect jobs in 2022, according to the Energy Ministry. To put that in context, the number of all Ecuadorians working in the formal sector, according to the July 2023 National Institute of Statistics report, is 2.9 million.

Investors on Edge

The referendum’s result will not only impact citizens but also the national government’s finances, which in turn flow to provincial and local governments for various programs. The state currently receives $1.2 billion annually (out of about $20 billion state income) thanks to the oil extraction in block 43.

In 2022, Ecuador’s most exported product was oil, accounting for 35.5 percent of the total, according to the Ministry of Production. Further, the Ecuadorian Hydrocarbon Industry Association asserts that oil extraction generates 30–34 percent of the state’s annual income. The association states that the income Ecuador receives from oil extraction represents an average of 11.3 percent of its GDP. Block 43 has been the highest-producing location in Ecuador.

Ceasing operations in oil extraction is not a simple task. Ramón Correa, chief executive of Petroecuador, contends that the company needs $500 million to remove the oil extraction platforms in block 43. He asserts that indigenous communities living in nearby areas will stop receiving around $40 million in compensation—to be paid incrementally over years of use—due to oil extraction in their territories. In June, two of seven indigenous communities adjacent to block 43 demonstrated publicly in favor of oil extraction in the zone. Perhaps because there was disagreement among members, the other communities did not take a clear stand and demonstrate in a unified manner.

In block 43, Correa clarifies, the state has already invested over $2 billion that will be lost when companies cease their operations. An anonymous worker from block 43 shared with La Posta the immense complexity and expense of removing the machinery that firms are currently using in the territory.

Correa also states that foreign and local oil companies operating in Ecuador will file lawsuits against the country for violating their contracts and forcing them to cease their operations. A La Posta report estimates that companies operating in block 43 could file a lawsuit for around $500 million against the state.

According to Walter Spurrier, vice president of development NGO Esquel, the damage to the state’s finances is even costlier than originally thought because “companies expected to increase their barrel production from 55,000 per day to 125,000 per day in the upcoming years.” He adds that there will be an increased presence of illegal loggers poaching in the zone, since oil workers and their security prevented unauthorized individuals from entering the area.

For Spurrier, ceasing operations in block 43 sets a negative precedent for investment in all productive industries because investors will never know if a new referendum will bring down their operations. For him it is incomprehensible that a “referendum proposed by citizens can make billions of dollars already invested in an industry go to waste.”

Espinosa Goded remains optimistic regarding mining (rather than oil) extraction in the YNP: “We saw an example in the vote of citizens in the Orellana province. Only locals can vote in referendums regarding mining. So I stay positive that in future referendums locals will vote in favor of continuing any operations.”

Although the referendum’s results dictate that neither the state nor foreign companies will be able to continue extracting oil from block 43, the strategy for abandoning the already-built wells and platforms is still new and uncertain. The Constitutional Court ruled in May that if the vote in favor of halting oil operations won, companies would have a one-year period to stop their operations. However, Roberto Aspiazu, vice president of Ecuador’s Chamber of Energy, believes the period is unfeasible. The one-year timeline for ceased production and machinery removal—likely to be violated—could presumably also incentivize a rush to extract while still legal.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.