Venezuela is in the midst of a crushing economic crisis, with scarce food and medicine, hyperinflation, and relentless violence. The nation’s Supreme Court commonly nullifies the decisions of the Venezuelan parliament, which holds the opposition majority. Most recently, the parliament demanded that Nicolás Maduro resign, declaring that he had abandoned his position, only to be nullified yet again.

In Ecuador, the harassment of journalists increases day by day and defies belief. The executive and legislative branches impose bills and decisions without regard for their social impact, and incumbents reform the electoral system only to rig it in favor of themselves. Democracy decays, while populism and authoritarianism gain ground.

According to Kaiser and Álvarez, populism diminishes individual freedom and divides society into purported oppressors and victims. Moreover, Latin America’s populist leaders trot out the “neoliberal” straw man to demonize market liberalization, obsess over equality and inclusion, and use democracy as the façade for their authoritarian regimes.

The authors believe that populism is not merely a strategy to gain power, but rather it necessitates an ideology that fosters regulatory actions to garner public attention. Without them, populist political and economic institutions would fade. Consequently, populism is more effective in regimes with weak institutions, generalized corruption, crises, and a high degree of government interference.

Low economic and weak democratic standards are fertile grounds for populist leaders, necessary but not sufficient conditions. Charisma and intellectual credibility are important tools for the populist agenda. Usually, populist leaders use Orwellian “newspeak” to reduce the meaning of language, forcing the populace to conform their thoughts towards those of the government and making it impossible to conceive any other point of view.

The authors explain that Latin American states lack rule of law, separation of powers, and protection of individual rights. They believe a liberal republicanism, similar to the US political system, would have better outcomes. Nevertheless, we have to come back down to earth and face the reality: the latest results of the Latinobarómetro survey — with 20,000 respondents throughout Latin America — show approval towards democracy has diminished. Even worse, approval of heavy-handed government is increasing.

Another analysis, Populism and Competitive Authoritarianism in the Andes, written by S. Levitsky and J. Loxton, describes populist leaders as political outsiders who use anti-establishment and socially inclusive rhetoric. The adherents seek to destroy checks and balances and gain an electoral mandate that buries the established elite.

In particular, countries that face institutional weakness and political party collapse are vulnerable to the most detrimental effects of populism. According to these professors, populist governments can then turn into competitive authoritarian regimes.

El Engaño Populista is a useful guide to examine the contemporary phenomena in Latin American politics. It has the potential to reach a wide audience due to its easy reading and attractive style. Yet it is limited by its theoretical basis: the authors rely too heavily on classical liberalism to support their thesis. This myopic approach may affect the credibility of the book for those who don’t understand or share the classical-liberal perspective.

Populism isn’t inherently bad. Actually, it can be an effective means to transmit ideas and to achieve political goals for the betterment of society. Donald Trump, for example, used populism to ignite conservatives in his campaign for the US presidency. It is a political communication style that displays proximity to the people. In fact, the solutions Kaiser and Álvarez propose do not completely discard populist practices, such as educating voters with common-sense ideas about economics and improving the emotional intelligence of communicators.

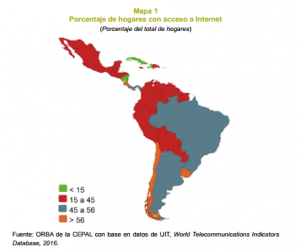

One challenge for the authors is that they rely heavily on new communication technologies to promote alternatives and raise awareness, yet internet access is still very limited in Latin America. According to the last report of The State of Broadband in Latin America and the Caribbean, only 55 percent of the population used the internet in 2015. Moreover, internet access is lower in countries where the 21st-century socialists have succeeded. Therefore, reliance on the internet for communication will fail where it is needed the most.

We should not discard social and technological media, yet we have to be conscious of its constraints and the necessity to use other means, as well. Perhaps, promoting our ideas through the academy and classical-liberal think tanks is a feasible way to challenge populism. However, we need to build a strategy and support each other throughout the region. These ideas will fail to gain traction if they are competing with socialists who actually get out in the real world and speak directly to the “man on the street.”

This book invites us to struggle with the problems of 21st-century socialism and the consequences of populist governments with weak democratic institutions. But it fails to explore realistic communication strategies and systems to reach as many people as possible. Although populism has been thus far largely used to spread socialism throughout Latin America, it can and should also be used to spread competing ideas of freedom and capitalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.