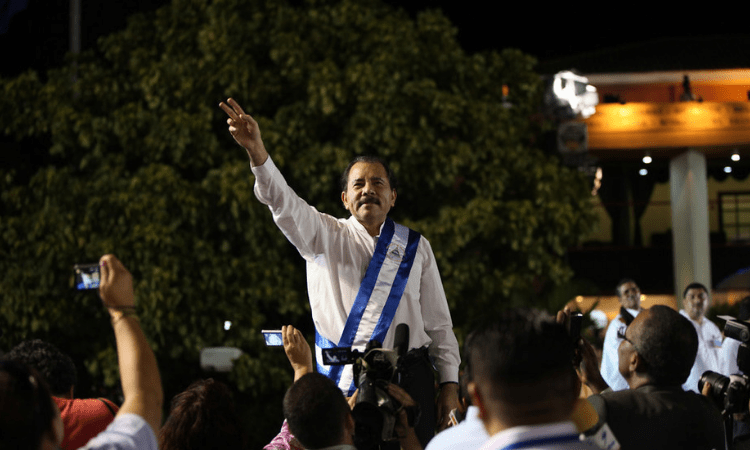

If Augusto “César” Sandino were alive, he might lead a revolution against his own movement. The leader of the National Sandinista Liberation Front, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, has transitioned from exiled guerrilla to multi-billionaire tyrant. Under proclaimed Sandinistas, Nicaragua is witnessing a new exodus, as Ortega outlaws protests and chases students from the country.

Ortega’s journey to the presidency was fraught with underhanded maneuvers. After losing reelection in 1990 against a US-backed candidate, Ortega realized—like Hugo Chávez in Venezuela—he would have to conceal his true intentions if he wanted to regain power. He secured political support from diverse sectors and started including both progressive and conservative talking points with the sole objective of attaining and remaining in office.

At the turn of the century, an electoral reform gave him an opening. The new law reduced from 45 percent to 35 percent the votes a presidential candidate had to secure to win the election without a runoff. Ortega got 38 percent in 2006 and won, despite suspicions of fraud. In 2017, the US Treasury Department sanctioned Roberto Rivas, then president of Nicaragua’s Supreme Electoral Council.

At the onset, the Ortega administration did not rock the boat. It continued repaying International Monetary Fund debt and implementing broadly liberal economic reforms. For example, Ortega refrained from boosting state payrolls, despite union pressure.

The Sandinista government worked to attract foreign direct investment by welcoming more multinationals. Under the guise of privatization, Ortega handed over the state’s energy companies to family members and cronies. He passed free-trade agreements with the United States in 2006 and with Taiwan in 2008. Along with other Central-American countries, Nicaragua joined trade zones with Mexico in 2011 and with the European Union in 2012.

The country’s business elite were pleased with Ortega during his first decade in power. Giving the Superior Council for Private Enterprise (Consep), a consortium of major firms, a say in national economic matters was a crucial Ortega tactic.

Similarly, to garner popular support, Ortega launched ambitious social programs for the poorest Nicaraguans who mostly work in the underground economy.

A Man of God and Fortune

Given that Nicaragua is a highly religious country, Ortega also made it a point to present himself as a devout Christian. On the election trail, the late archbishop of Managua, Miguel Obando, officiated Ortega’s remarriage with the charismatic Rosario Murillo, Nicaragua’s own Evita Perón, now first lady and vice president. Once in power, Ortega appointed Obando to head an influential commission. He also gave the Catholic Church and conservative parties a long-cherished goal: overturning a 100-year-old law that allowed abortion under limited conditions.

Behind the scenes, Ortega also orchestrated a broad surveillance system with spies in the judiciary, the military, and other state institutions. He had private-sector employees secretly working for the government, and the police wiretapped phones at his whim.

By the time of his second presidency, long gone were the days of personal austerity and revolutionary preaching. Nicaragua channeled over US$4 billion from Venezuela through Albanisa, an oil and gas joint venture between the Venezuelan state-run PDVSA and a firm controlled by Ortega’s family. This slush fund financed Sandinista handouts and his own luxurious lifestyle.

Albanisa grew to over 1,500 employees and several subsidiaries, including a bank, a wind-energy project, an airline, gas stations, and more. The World Ultra Wealth Report 2018 puts Ortega’s fortune at $3.6 billion. When elected, he had a fraction of that: $217,000.

Ruling the country has also proved profitable for Ortega’s closest allies. Presidential advisor Francisco López has created a clandestine network of construction companies. Bayardo Arce, an economic advisor, has amassed a fortune by trading grains, and Gustavo Porras, the National Assembly president, has fashioned himself as a livestock magnate.

In 2013, as the Venezuelan economy spiralled out of control, Ortega tapped into a larger source of foreign funds: China. He announced the construction of the world’s largest canal with the help of a Chinese tycoon. The bill: $50 billion. However, the project has yet to take off, and probably never will, but investors have already poured millions into the country.

Armed with his own deep-state plutocrats, Ortega felt emboldened to go on the offensive in politics. Taking a page out of Chávez’s book, the ruling party rewrote the country’s constitution in 2014 and cleared the way for Ortega’s reelection for life. The Sandinistas have since expelled opposition lawmakers, shut down newspapers, and prosecuted critics. Ortega and Murillo easily won the 2016 election, with barely any international observers.

The country has been mired in social unrest since April 2018, when students and activists began protesting against a social-security reform that increased taxes and cut benefits. According to local human-rights organization ANPHD, 2018 clashes with the police left 545 dead and 4,587 injured. Over 1,000 demonstrators disappeared. The protests are ongoing, which have morphed into a denunciation of the regime’s rampant corruption and violence.

As the world focuses on Nicaragua, local business elites and the Catholic Church have turned against Ortega. However, it is too little too late. The Sandinista dictator learned from the Chavistas how to game and usurp democracy. Ortega and his cronies possess the reins of power and remain firmly in control of the country with no end in sight.

Editor’s note: the Nicaragua experience should be a warning to neighboring nations regarding the risk of wolves in sheep’s clothing and the potential for tyrants to hijack democracy. Guatemala recently narrowly avoided such a fate.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.