San Carlos University (USAC) notified Guatemala’s Congress on March 5 that the previous day it had appointed Gloria Porras as its magistrate to the Constitutional Court (CC), the country’s last word on judicial matters. Congress drew criticism of corruption on April 13, including from the US State Department, when it swore in other appointed magistrates but not Porras.

Our intention here is to inform the public of the facts and the law regarding Porras’s nomination.

The CC consists of five principal magistrates and five alternates, who all serve five-year terms. The eighth term began on April 14, 2021, and ends in 2026. The president, Congress, and Supreme Court each appoint one principal and one alternate magistrate, which are not subject to challenge. The Bar Association and USAC each appoint one principal and one alternate, which are subject to challenge. Both latter institutions received challenges to their latest appointment processes.

The Law of Injunction, Habeas Corpus, and Constitutionality (Injunction Law) provides for the USAC and Bar Association appointees from the previous period to remain in their posts until challenges to the new appointees are resolved. After Guatemala’s College of Professional Associations rejected the challenge to the Bar Association’s process, its two appointees became final, and the Congress swore them in on June 3.

USAC principal magistrate José Francisco de Mata, however, continues in his post because challenges to Porras’s nomination remain in litigation. Congress swore in the USAC alternate, who would take Francisco de Mata’s place if he were absent.

OFICIAL | El Consejo Superior Universitario (CSU) ha designado a Gloria Porras y Rony López como Magistrado Titular y suplente, respectivamente, ante la Corte de Constitucionalidad 2021-2026 por parte de la #USAC. pic.twitter.com/AIMtRdq2Df

— Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala #USAC (@InfoUsac) March 5, 2021

Elongated Voice Voting

After six hours and 12 rounds of voice voting by 38 members of the USAC Supreme Council (CSU) on March 4, the CSU declared Porras the winner. Omar Ricardo Barrios received more votes than Porras in the first two rounds but not a majority. Even after remaining as the only two candidates, neither Barrios nor Porras obtained a majority and were tied through 11 rounds.

There was alleged intimidation exerted on CSU members to vote for Porras. Some members, who requested anonymity given fear of reprisal, told the Impunity Observer the US embassy called members and demanded they vote for Porras.

CSU architecture student Lila María Fuentes voted for Barrios in the first 11 rounds and said Porras’s candidacy was not only irregular but illegal. In an unexplained about-turn, Fuentes voted for Porras in the 12th round.

A CSU member, who requested anonymity, told the Impunity Observer that Human Rights Ombudsman Jordan Rodas called members and said not voting for Porras would be a path to corruption and a failed state. One member pushed back against Rodas and told him that Porras did not fulfill the eligibility requirements. Rodas has not accepted the Impunity Observer’s invitation for an interview to get his explanation.

In an April 23 communiqué, the Prosecutor General’s Office gave five days to the USAC rector to inform the prosecutor “whether he knew of any CSU members being pressured to vote in a specific manner.”

In holding a voice vote rather than a secret ballot, the CSU held the election inconsistent with the university’s own established laws. Numerous challenges arose regarding the voice vote, since it did not protect the identities of members when voting. The CSU brushed these challenges aside and said USAC statutes requiring secret ballots did not apply to the CC election. Presumably, the CSU applied this interpretation, exempting itself from USAC election laws, for the rest of the voting procedure as well.

The Impunity Observer consulted former constitutional law professor José Luis González. He explained that USAC election laws do apply to the election of the designee for the CC. Since the article of the Injunction Law regarding the CSU designation of CC magistrates does not specify a voting procedure, another article of the Injunction Law and two articles of the Judiciary Law apply. These hold that authorities will apply procedures for similar or analogous cases or situations.

USAC election laws specify that voting is by secret ballot. Further, if the first two rounds of voting fail to produce a winner, the CSU will hold a runoff the next working day—in contrast to what happened—between the two candidates with the most votes. González says applying any other voting procedure is arbitrary.

A Flurry of Legal Maneuvers

The CSU’s March 5 notification to Congress that Porras was their CC designee did not include, as required by the Judiciary Law, a statement regarding challenges. The period for filing challenges is five days after notification of the act. Only one day had passed, and participating candidates and registered interested parties had received no notification.

On March 8, Congress’s legal office sent a letter to the USAC with questions about challenges. The USAC secretary general answered the same day that there were no challenges as of then and that the procedure for challenges is regulated by the Administrative Litigation Law (ALL).

The CSU did not notify any of the participants or interested parties of Porras’s designation, as the law requires.

Despite no official notifications, five participants and interested parties filed challenges directly to the CSU, as the ALL prescribes. The CSU rejected them all without processing them or notifying the challengers.

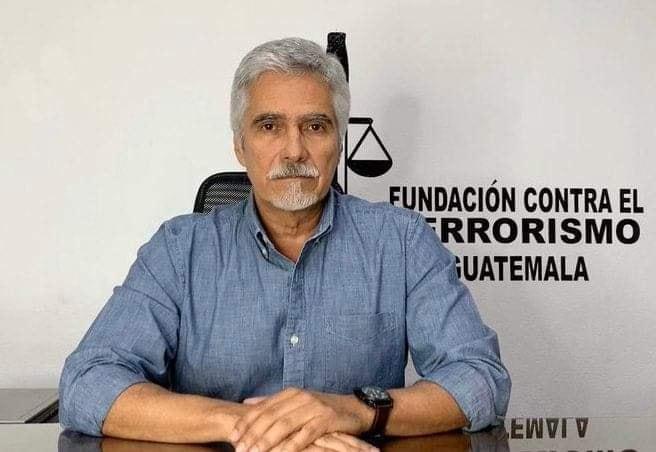

The CSU, for example, rejected a challenge by the Foundation Against Terrorism (FCT) for lack of standing. The FCT had formally expressed interest in response to the CSU’s public convocation of the process and had presented formal objections to two candidates.

Eventually, after the FCT appealed to the judiciary, the CSU began notifying the FCT and others.

The CSU rejected a challenge filed by one participant, lawyer Roberto Estuardo Morales, for arriving after the challenge period had expired. The CSU asserted that the public nature of the event triggered the period for challenges.

Morales did not receive a CSU notification regarding the rejection of his challenge. However, having heard about the decision, he petitioned for and obtained an appeals court ruling that suspended the USAC designation process and ordered the CSU to process his challenge.

On April 13, the USAC secretary general sent another letter to Congress, stating that the ALL did not apply to the USAC designation of CC magistrate. This same official, contradicting herself, had informed Congress in writing on March 8 that the ALL regulated challenges to the designation.

González explains that the USAC had sent “certification of Porras’s designation while the process was ongoing, without having notified the candidates and interested parties. It appears the CSU wanted Congress to swear in Porras before the constitutionally challengeable process had concluded.”

Congress scheduled the swearing in of new magistrates for April 13 and swore in the designees of the president, Congress, and Supreme Court but not those of the Bar Association and only the USAC alternate. The congressional record states Congress received notification that day from the appeals court suspending the USAC principal-magistrate designation process and ordered the ALL be applied. Congress stated it could not swear in the USAC principal designee before all challenges had been definitively resolved.

US Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Brian Nichols characterized Congress not swearing in Porras on April 13 with other magistrates as a “maneuver (that) undermines Guatemala’s commitment to an independent judiciary and addressing systemic corruption.”

Challenges to USAC Process Proliferate

In its official act to begin processing Morales’s challenge, the CSU stated it did so “despite disagreeing with [the court] given that [its order] violates USAC autonomy.” The CSU disagreed with being subject to the Administrative Litigation Court.

On June 23, the CSU officially rejected Morales’s challenge. On that same day, they said there had been 13 injunction requests, eight suspended and five being processed. One of the latter was Morales’s challenge.

The CSU identified three main points of dispute: (1) the voice vote, (2) the university teaching-experience requirement, and (3) required notifications.

- Voice Vote

The CSU argues the Constitution requires a voice vote based on its statement that “all administrative acts are public.” They say this takes precedence over lower-ranking laws that call for a secret ballot for USAC voting.

The opposing argument is that only the CC can determine if a lower law is unconstitutional, and everyone must obey a law until the CC rules it unconstitutional.

In addition, the nature of public administration does not require being able to see how someone votes. The public can still see the process without seeing for whom individuals vote. Secret ballots are essential for democracy, since they avoid pressure on voters and more accurately reflect voter wishes.

Guatemala’s solicitor general has stated on the record that the provision of the Constitution the CSU cited did not justify a procedure different from what applicable law requires.

The CSU counters that its members renounced their right to secrecy when they approved voting by voice for their designation to the CC. The CSU also states its members voted by voice in the 2011 and 2016 elections for their CC designee.

The opposing argument is that the vote to approve voice voting was also done by voice vote, which opens the door to coercion of CSU members, and the 2011 and 2016 processes are irrelevant. Acts in violation of the law are null and void and produce no effects, especially precedent. Further, the right contained in the law established by the constituent assembly that specifies secret ballot for the USAC process cannot be renounced by the CSU.

The CSU holds that the USAC election rules, which specify a secret ballot, apply only to the election of USAC authorities and not to its designation of CC magistrates. The opposing argument is when the law does not specify procedures, the Injunction Law and the Judiciary Law require authorities to apply procedures for similar or analogous cases or situations. This means the CSU must apply the USAC election rules.

The CSU says its members have no right to a secret ballot because they are elected. The counterargument is that for the USAC to hold an election contrary to current law, it would have to create and codify a separate procedure to apply to electing designees for magistrate of the CC.

- Teaching Experience

The Injunction Law gives preference to USAC candidates for CC magistrate who have university-teaching experience. The CSU interprets the language of the law as “could” and not “must” give preference. The opposing argument is that the Judiciary Law establishes the meanings of words according to the dictionary of the Real Academia Española. The words in the law obligate CSU members to choose a candidate with university teaching experience over one without it.

In her résumé, Gloria Porras lists teaching experience as having given seminars to various groups. This is not university-teaching experience. Omar Ricardo Barrios, who received more total votes than Porras during 11 rounds of voting, has 19 years of teaching experience at USAC and at Rafael Landivar University.

- Notifications

The CSU states that the public nature of the designation process for CC magistrate is sufficient for participants and interested parties to present challenges.

The opposing argument is that two articles each of the ALL and the Civil and Mercantile Procedural Code obligate the CSU to personally notify the participants and registered interested parties. To be able to properly challenge an act, the challenger must have an official copy of the act. Otherwise, it is impossible to know the reasoning of the act.

How Litigation Unfolded

On July 5, the CSU notified participants and interested parties of its June 23 act—its rejection of Morales’s challenge. On July 15, Morales sued the CSU in the Administrative Litigation Court.

On July 13, the FCT petitioned the CC to enjoin (halt) the Congress from swearing in Porras while challenges were pending against the CSU process. The FCT cited the threat of violating due process and the law if Congress were to swear in Porras.

The CC ordered the CSU to present all information regarding the designation process. It also ordered information from the 5th Circuit of the Administrative Litigation Court (Fifth Circuit), which was processing Morales’s claim against the CSU.

On August 11, the Fifth Circuit notified Congress it had suspended the CSU’s rejection of Morales’s challenge. On August 12, the acting president of Congress informed the representatives that, due to the Fifth Circuit’s notification the previous day, they would be unable to address the Porras appointment as they had agreed in their August 10 session.

The acting president said the USAC designation process for CC principal magistrate had been suspended by the Fifth Circuit’s ruling. The legal process would determine “if in said designation, the CSU complied with the requirements of the law.”

With information from USAC, Congress, and the Administrative Litigation Court, the CC identified a risk of Congress swearing in a magistrate from a process that had violated the constitutional election requirements and was not yet complete. The CC granted a provisional injunction, ordering Congress not to swear in Porras.

On December 13, the Sixth Circuit of the Administrative Litigation Court ordered the CSU to process the FCT challenge. Presented to the CSU on March 9 and rejected on March 12, it is against the CSU appointees for principal and alternate magistrates. The challenge is against the voice vote and Porras’s lack of teaching experience.

US State Department Doubles Down

As on April 13, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Brian Nichols criticized Congress. On August 18, he commented on Congress’s August 12 declination and the CC ruling: “[it] prevented the swearing in of a duly elected magistrate in a process that had been carefully reviewed and affirmed by the electing institution in accordance with Guatemalan law.” Nichols added the ruling “is disturbing as it supports the motions filed by an organization with a documented history of undermining democratic processes.”

Nichols was referring to the FCT. Its petition, granted by the CC, provisionally prevented Congress from swearing in Porras. The State Department had already sanctioned the FCT president and two of its lawyers as corrupt and canceled their US visas.

González counters:

“The magistrate the CSU designated has not been duly elected until all challenges have been definitively resolved. The State Department appears ignorant of the facts of the case and Guatemalan law, which is clear regarding the process of designation of the USAC magistrate.

It is absurd to state that exercising civil rights by petitioning courts can undermine the democratic process. Demanding compliance with the constitutionally guaranteed right of due process is an integral part of democracy in Guatemala and other democratic countries, including the United States.

The role of the FCT is like that of Judicial Watch in the United States. Would Nichols accuse them of undermining democracy in his country? The State Department sanctioned the FCT personnel in violation of the presumption of innocence and their right of defense, which is antidemocratic.

Nichols’s comments lend credibility to the Impunity Observer’s sources who insisted on anonymity—because of fear of reprisals—before providing information regarding US embassy pressure on members of the CSU to vote for Porras.”

What Will Come of the USAC Designation

The outcome of the USAC designation process for CC magistrate remains uncertain. Three possibilities exist: (1) the judiciary resolves all challenges in CSU’s favor and Congress swears in Porras; (2) the judiciary annuls the process for having violated the law, forcing the CSU to convene a new designation process; or (3) the process does not end during the 2021–2026 CC term.

Meanwhile, José Francisco De Mata will continue on the court as USAC’s principal designee. His presence depends on the resolution of the process to lift his immunity currently in Congress and the consequent actions of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the judiciary if Congress lifts his immunity. That could place the USAC alternate in his position.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.