The UN Office for Project Services (UNOPS) has worsened medicine shortages in Mexico’s public health system.

In July 2020, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) signed a cooperation agreement with UNOPS to outsource the procurement for medicine purchases. His stated goal was to fight cronyism and corruption.

UNOPS, however, has erected more barriers to entry in the form of supplier requirements. One of the most controversial is that medicine suppliers comply with gender-equality policies. This criterion derives from the UN-promoted 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Since only a few pharmaceutical companies can demonstrate compliance with the gender-equality requirement, UNOPS has failed to purchase enough medicine. In June 2021, UNOPS sent a letter to Mexican authorities claiming they could not purchase 653 drug types. These account for more than half of the total medicine supplies list.

Medicine shortages are undermining health and creating incentives for corruption, since approved supplier status has become more lucrative. This investigation aims to identify how the UNOPS operation contributes to drug undersupply in Mexico’s public health system and the consequences.

To unveil how UNOPS cooperation is unfolding, the Impunity Observer interviewed two public-health system experts. They are Irene Tello, coordinator at Zero Impunity, and Andrés Castañeda, coordinator at the Nosotrxs Foundation. Both nonprofit organizations are members of Zero Medicine Shortages (ZMS), which monitors Mexico’s medicine supply.

When Shortages Began

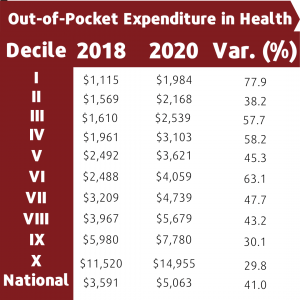

The nonprofit Economic Research Center has revealed that health-care spending among poor households soared by 78 percent between 2018 and 2020. This stemmed from reduced medicine supplies. On average, the out-of-the-pocket expenditure on medicines for Mexicans was 41 percent more in 2020 than two years prior.

ZMS points out that people diagnosed with cancer, diabetes, hypertension, and HIV report the most medicine-shortage complaints. For them, treatment discontinuation is life threatening. Further, patients with health issues could lose their opportunity to receive a transplant. The latter is the case of an anonymous patient reported by ZMS.

As a consequence, counterfeit-medicine sales have increased. Counterfeit medicine is a risk to the patient’s health; it is likely to be polluted, contain harmful doses, and/or have expired.

Since 2019, the medicine shortage has become more evident. According to a ZMS report, unfilled prescriptions went up from 0.9 percent in 2018 to 10.3 percent in 2021.

A Changing of the Guard

When AMLO took office in 2018, he announced a reform to medicine procurement. AMLO strongly opposed the previous system, because it allegedly fueled a pharmaceutical oligopoly. It involved the most prominent Mexican firms, such as Pisa, Calca, and CPI. He also argued that “previous administrations protected medicine distributors.”

Castañeda and Tello told the Impunity Observer that the medicine procurement system—in force between 2014 and 2019—was relatively effective. Mexico’s Social Security Institute handled the procurement processes, including distribution.

Previously, unfilled prescriptions remained stable over the years. ZMS reported a decrease in unfilled prescriptions from 2017 to 2018. They went from 1.1 to 0.9 percent. Castañeda and Tello highlighted that the system still had flaws in its supply chain. However, shortage rates remained steady, and medicine purchases were more transparent.

Tello said: “The AMLO administration was arrogant in criticizing the old procurement system when it was successfully providing medicine for public hospitals across the country. Now, the situation is more complex. Officials and UNOPS were not qualified for this.”

In early 2019, AMLO made his first changes to the medicine procurement system. After Congress passed reforms to the Public Administration Law, the Secretariat of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP) became responsible for buying publicly provided medicine.

In a statement, the AMLO administration declared: “This new system, which is part of the government’s plan to fight corruption, will guarantee the medicine supply in public hospitals.” However, the SHCP struggled to obtain the medicine.

In May 2021—after SHCP proved unsuccessful—AMLO announced that the Mexican Health and Well-Being Institute (INSABI, Mexico’s health ministry) had signed an agreement with UNOPS. The stated purpose was “to strengthen the public health system in the country.”

In a press conference, he revealed Mexico would pay over US$2 billion to UNOPS to alleviate the medicine supply problem. According to Health Secretary Jorge Alcocer, however, the $2 billion payment only accounts for 76.6 percent of what the central government will pay to UNOPS.

The agreement will last until 2024, when the government can choose to renew it. From 2014 to 2019, government spending on public health decreased, relative to Mexican GDP, from 2.89 to 2.68 percent. In 2020, after the INSABI-UNOPS agreement, public health spending rose to 3.15 percent. Despite increased spending, the medicine shortage has increased over the past three years.

How UNOPS Has Impeded Supply

Castañeda contends: “Neither the government nor UNOPS were aware of the complexity in the medicine procurement system.” Still, UNOPS asked for most of the payment up front. According to the Mexican General Acquisition Law, the government could only pay after receiving the medicine. To secure the UNOPS deal, Congress reformed the legislation.

“Overcoming this legal restriction took a long time, and [the delayed payment] slowed down the medicine procurement process for Mexican hospitals.” Nevertheless, this was not the sole factor that amplified the medicine shortage.

In addition to federal procurement requirements, UNOPS has imposed other conditions on pharmaceutical companies. Many have struggled to meet these requirements and have been unable to supply medicines for the public health system.

Among the usual requirements, companies must prove their availability and capacity to fulfill the order. They should also present the medicine’s price, quality, and other properties.

Since UNOPS focuses on UN and SDG agendas, it also assesses the ethical aspect of each company. According to its Procurement Manual: “The United Nations is determined to engage in commercial operations only with companies that share our vision of human rights, social justice, human dignity, and respect for rights equality between men and women.”

Therefore, UNOPS mandates that companies, should they wish to deal with the public health system, meet socially oriented requirements. Gender equality is one of the most important conditions. The requirement within the UNOPS manual is vague, with an eye towards 50 percent of each gender. The precise acceptable gender cutoff is not public. This appears to leave wiggle room for discretion and subjectivity over which firms are in compliance.

The requirements get obscure, since companies must attest that neither the company nor any of its workers contribute to anti-personnel-mines production. Amid a high degree of economic informality, firms open themselves up to self-incrimination. They must issue guarantees that they do not hire children and that there is no sexual exploitation in the workplace.

Castañeda explains that many pharmaceutical suppliers, especially smaller firms, cannot fulfill the new requirements. For him, these conditions have contributed to the slowdown in medicine supply for public hospitals.

Another reason is lack of coordination. Contracted companies struggle with uncertainty and cannot prepare large medicine orders in advance. Due to miscommunication between officials and UNOPS, they have not received timely information on needed drug types and quantities.

In light of the prevailing undersupply, the government took over the task midway through the UNOPS agreement. The AMLO administration tried to buy the missing medicines, particularly the most critical. It still failed to fulfill demand.

“Despite UNOPS’s good intention, its agenda ended up contributing to the lack of medicines in Mexico,” Castañeda said. For him, Mexicans are paying the price for UNOPS’s failure.

Opaque Procurement

Castañeda explains that a system that does not work opens the door for corruption. The government is using taxpayer dollars—through no-bid, ad hoc contracts—to buy the medicine that UNOPS is failing to purchase. Public hospitals are circumventing UNOPS and, as best they can, acquiring medicines from other suppliers.

In November 2021, María Pérez—a legislator from the National Action Party (PAN)—accused the AMLO administration of turning a blind eye to UNOPS opacity. The 2021 medicine procurement process was full of irregularities.

UNOPS delayed the process for six months. Then it did not release timely, relevant information on selection criteria and results. However, periodicals at home and abroad have picked up on the escalating shortages. As of May 2021, out of 724 million items bought to supply hospitals that year, only 60 million were delivered or had a shipping order.

Pérez presented a letter to Mexico’s Transparency Institute seeking accountability and pressure on UNOPS. She said the fact that UNOPS has no obligation to be held accountable incites corruption in an operation that entails billions of dollars from Mexican taxpayers.

Pérez claims to have presented 21 information requests regarding medicine purchases. However, she has received no response. This is no surprise for her. She believes the government and UNOPS have no reliable paper trail for most of them.

In a similar vein, Tello told the Impunity Observer that “with the new system in cooperation with UNOPS, procurement information is not widely available. UNOPS does not release data about medicine purchases. UNOPS publishes engaging content about alleged achievements, but we do not know if they are completely true.”

With the procurement system in force until 2019, the numbers were available and clear. The information was accessible on the internet and in the offices of the relevant federal agencies.

The INSABI-UNOPS agreement has not only lacked positive results but fueled the medicine shortage in the Mexican public health system. The procurement system lacks transparency and creates the wrong incentives, leading to further corruption.

Disregarding complexity and shortcomings, AMLO outsourced a vital role to an ideologically driven UN agency. For example, UNOPS puts equal numbers of female and male employees in pharmaceutical companies ahead of people’s lives.

Mexicans are hurting, and the poorest are the first to feel the pinch of a failing public health system. In addition to more taxpayer dollars devoted to medicine supply, the people have raised their out-of-the-pocket expenses in pharmaceuticals over the past four years.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.