The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), founded in 1959, has increasingly devoted itself to promoting social entitlements (positive rights) over natural rights. The governments of Guatemala, Colombia, and Ecuador have openly said this is due to its leftist ideological bias, which is now beyond doubt.

In its 2021 annual report, for example, the IACHR condemned abortion prohibition in Guatemala as an infringement on women’s rights. Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei, on the other hand, highlighted before the Organization of American States (OAS) the right to life from the moment of conception—as noted in OAS’s very own American Convention on Human Rights.

The objective of this investigation is to examine, delineate, and open the conversation regarding collectivist dominance in the IACHR, a topic that receives scant attention. For this purpose, the Impunity Observer interviewed Jason Poblete, a human-rights lawyer and president of the Global Liberty Alliance; Mauricio Alarcón-Salvador, the executive director of the Foundation for Citizenship and Development (FCD); and Sabrina Peláez, a member of Global Liberty Alliance Uruguay.

An Overview of Human Rights

The international community (member-state organizations such as the United Nations and the European Council) classify human rights into three generations: (1) civil and political, (2) economic and social, and (3) solidarity.

First-generation human rights provide civil and political faculties, ensuring individual freedom. These include the rights to life, voting, property, free expression, and equality before the law. These are also known as natural rights.

Second-generation human rights, in contrast, expand the role of the state in social, economic, and cultural matters. Under this framework, governments should provide universal education, medical care, housing, and employment. Third-generation human rights include national and tribal self-determination, socioeconomic development, and a healthy environment.

In the ongoing debate, human-rights organizations and scholars are advocating for newer and broader generations of rights. The proposed fourth and fifth generations seek protections for animal species and other non-human actors, as well as universal access to the internet and a litany of other proposals.

Peter Myers, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, states that rights beyond the first generation “are conceived not as the exercise of human faculties but rather as the fulfillment of human needs.” For Myers, these rights make up a “needy” conception of human beings and muddy the fundamental basis for rights.

The Current State of the IACHR

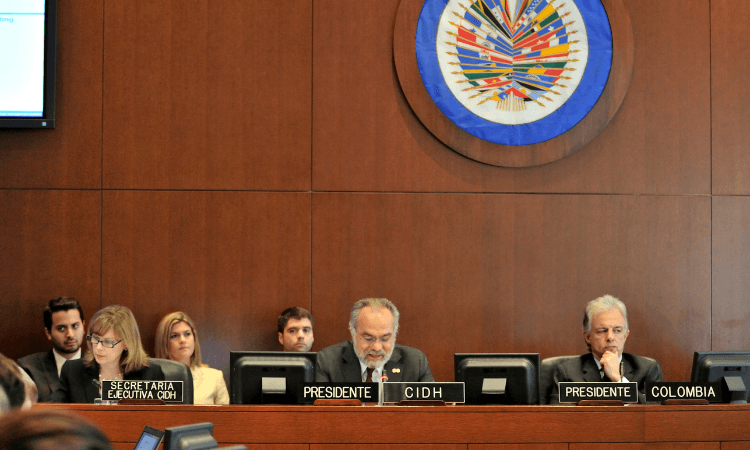

The IACHR is a self-described autonomous arm of the OAS, tasked with upholding human rights on the continent. Totaling 152 employees, the IACHR is made up of 63 staff members, 79 consultants, three associate professionals, and seven commissioners.

Financed by member states and the international community, the IACHR budget splits into regular and specific funds. Totaling $10.07 million, the 2021 regular fund accounted for 58 percent of its yearly financing. The regular fund comes from the OAS budget through contributions from its main donors: the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Specific funds amounted to $7.25 million. Member states such as the United States, Canada, Mexico, Panama, and Costa Rica—and permanent observers like the European Union—contributed to these funds in 2021.

The regular fund finances routine operations. Since its personnel and financing are limited, Alarcón-Salvador points out that IACHR work has mainly focused on hearing cases of individual violations. Alarcón-Salvador—who has leveraged FCD efforts to promote freedom of expression and government transparency through the IACHR—explained to the Impunity Observer: “When a case moves to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the IACHR serves as a companion of the victim and his lawyers.”

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights is “an autonomous legal institution whose objective is to interpret and apply the American Convention.” Although apt for confusion, given the same abbreviation, the court is distinct from the IACHR but still part of the OAS system.

IACHR specific funds, in turn, finance projects that promote and target a particular right. While some focus on fostering justice, others promote rights for women, the LGBT community, Afro-descendants, and other population sectors—also known as identity politics.

In addition to following donor wishes, Alarcón-Salvador said the IACHR promotes and protects rights according to direct requests from constituents. The seven commissioners transmit those demands to the organization.

Elected by the OAS General Assembly, commissioners serve for four years. The IACHR Statute establishes that their role “is incompatible with engaging in other functions that might affect the independence or impartiality of the member or the dignity or prestige of his post on the Commission.” However, in recent decades, outspoken socialists in the region have occupied these positions, raising alarm bells regarding the IACHR mandate.

Currently, the seven commissioners are:

- Julissa Mantilla is rapporteur for Argentina, Barbados, Brazil, El Salvador, and Uruguay. Her topics are women and memory, truth, and justice.

- Stuardo Ralón is rapporteur for Cuba, Ecuador, Haiti, Paraguay, Peru, and Suriname. His topic is persons deprived of liberty.

- Margarette May Macaulay is rapporteur for Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Canada, Dominica, Dominican Republic, and Saint Lucia. Her topics are people of African descent and the rights of the elder.

- Esmeralda Arosemena is rapporteur for Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. Her topics are children and adolescents and indigenous peoples.

- Joel Hernández is rapporteur for Belize, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Saint Kitts and Nevis. His topics are human mobility and human-rights defenders.

- Roberta Clarke is rapporteur for the United States, Guyana, Jamaica, and Panama. Her topic is LGBTI persons.

- Carlos Bernal is rapporteur for Costa Rica, Grenada, Honduras, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. His topic is persons with disabilities.

Further, Pedro José Vaca is a special rapporteur for freedom of expression, and Soledad García is a special rapporteur for economic, social, cultural, and environmental rights. Neither focuses on a specific geographical location.

Leanings of Top IACHR Officials

We have examined the seven most recent IACHR commissioners and an IACHR secretary, who have left their posts since 2014, and distilled their public statements. Those individuals taking positions on controversial topics show themselves to be uniformly leftist.

A minority—three of the eight—did not have active public profiles nor accessible statements, so we have not been able to feature them here. These individuals could lean conservative, but not a single recent IACHR commissioner has made public statements supporting right-wing candidates or movements.

Paulo Abrao was IACHR secretary from 2016 to 2020. OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro rejected Abrao’s reappointment in September 2020. Abrao was subject to more than 60 accusations against him regarding workplace harassment and abuse of power.

Abrao openly supports leftist political movements in the Americas, especially in Brazil. Alarcón-Salvador revealed that Abrao was a member of the Lula Institute—a leftist think tank that honors former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

The Impunity Observer requested an interview with Abrao. Despite agreeing initially, he then ceased correspondence.

Antonia Urrejola—IACHR commissioner from 2018 to 2021—is now the foreign affairs minister of Chilean President Gabriel Boric. On Twitter, Urrejola frequently complains about right-wing political movements in Chile and the region.

In a 2013 tweet, she wrote: “I do not agree with today’s Chavismo, but when you understand the Venezuelan right-wing, you understand plenty of things.”

Luis Ernesto Vargas—IACHR commissioner from 2017 to 2019—also frequently criticizes Latin American right-wing governments via his Twitter account.

In a 2020 tweet, Vargas said: “I am convinced that not even [Nicolás] Maduro commits atrocities inherent to fascism and dictatorships … ultra-right governments have sunk Colombia.” He also attacks news outlets such as the conservative-leaning Semana Magazine in Colombia, calling it a pasquinade (tabloid).

James Cavallaro—IACHR commissioner from 2014 to 2017—is also active on Twitter. He constantly supports US progressive causes such as voting-rights legislation, defunding the police, and tighter gun-control legislation. He argues that Democrats are “toothless” and not “aggressive enough” toward Republican proposals.

Democrats on the offensive? That would be nice. But it’s become a party that calls in the punter on first down. https://t.co/jkRPWhWSob pic.twitter.com/mNyhwltzJ2

— James (Jim) Cavallaro (@JimCavallaro) July 12, 2021

Paulo Vannuchi—IACHR commissioner from 2014 to 2017—served as minister of human rights during the Lula administration in Brazil. He visited the former president in jail in 2018, when he was convicted on multiple corruption charges.

O ex-presidente Lula recebe nesta quinta a visita dos ex-ministros de Direitos Humanos Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro (governo FHC) e Paulo Vannuchi (governo Lula). Atualmente, Pinheiro é relator na Comissão de Direitos Humanos da ONU. https://t.co/Hp8q6t30ta

— Lula 13 (@LulaOficial) May 2, 2019

Although these are the most recent examples, there are countless cases of IACHR commissioners and members actively supporting the left across the region.

How the IACHR Became Stridently Leftist

The Inter-American system (the commission and the court) is there to respond to human-rights violations, which need not be partisan, but IACHR commissioners do not keep their leftist loyalties a secret. For Alarcón-Salvador and Poblete, the court is more technical and less politicized than the commission.

According to Alarcón-Salvador, the IACHR’s leftist bias stems from the lack of participation of civil-society organizations that hold other ideologies. He contends that since IACHR’s creation, “traditionally right-leaning or libertarian movements did not occupy these spaces to promote first-generation rights. This happened not only at the commission but at the entire Inter-American sphere.”

Alarcón-Salvador says he has had a close relationship with IACHR commissioners for the last 20 years: “It is undeniable that there is a bias in the organization because incumbent governments nominate its members.”

Alarcón-Salvador said that Mexico is an exception. This country still nominates people to the IACHR based on their professional qualifications instead of their political affiliations.

For Poblete—who also acknowledges a leftist bias in the IACHR—the commission should focus on the promotion of political and civil rights. Peláez, in turn, has not only witnessed a left-leaning IACHR but the prioritization of cases based on social entitlements.

Peláez told the Impunity Observer that this pattern is repeating itself across the region. One of her anecdotes comes from the Uruguayan Human Rights Institute. A case of modern-day slavery, a clear violation of first-generation rights, received “almost zero attention” when compared to cases pursuing social rights.

Could Reforms Address the Ideological Bias?

Since the 1959 founding, the IACHR has been subject to a long-standing debate about potential reforms. Human-rights scholars are constantly examining how the IACHR can improve to expand its impact and achieve its mission.

Poblete and Alarcón-Salvador hold different views on the topic.

For Alarcón-Salvador, IACHR participation has the potential to correct the commission’s course. He argues it is important for right-leaning or natural-rights advocates to occupy spaces like IACHR thematic hearings and case presentations. Their origins, he contends, still come from liberty and natural rights. The flipside is that if right-leaning actors do not participate, leftists will continue their hegemony by packing these spaces.

Alarcón-Salvador asserts: “occupying these spaces will generate equilibrium in the mid and long term between first-generation rights and other human rights.” The fact remains that the first verdicts from the court mostly addressed natural rights.

In his experience, Alarcón-Salvador has witnessed only a few—almost zero—libertarian or right-wing organizations ask for space to promote judicial independence, freedom of expression, freedom of association, and private property.

“These topics could well be discussed in the Inter-American system. The problem is the right-wing movements are not fighting for their seat at the table,” Alarcón-Salvador claims.

Alarcón-Salvador and Poblete agree that IACHR resources—such as thematic hearings and strategic litigation—are available and ready to be utilized. Poblete, however, told the Impunity Observer that the IACHR is currently promoting causes instead of cases, contrary to its original mandate.

While everyone can apply for the positions of executive secretary or rapporteurs, right-wing movements have shown a lack of interest, both experts contend. Leftist movements, therefore, have free rein. Taking that into consideration, Alarcón-Salvador says: “we do not have to stigmatize the space, but instead act realistically to take advantage of it.”

Poblete, in contrast, showed a preference for a reform to the Inter-American system. He argues that resources are scarce: they come from states, which means taxpayers. Therefore, cases going through the system should be limited to those with clear merits.

He opines that the path starts by tackling the root problem: the corrupt and failing judicial systems of member states. Then a reform should stress the IACHR focus on civil and political rights and make sure that the Inter-American system operates as a last resort.

His experience underlines the limited capacity of the IACHR and associated court: a case rarely achieves any justice in the Inter-American system. Since national and Inter-American justice lacks swiftness, resolutions arrive when human-rights violations have already taken their toll.

Poblete also contends that people and organizations should not be able to take their cases to the Inter-American system without first exhausting local courts. Peláez concurs with Poblete. She contended that in countries where the judicial system is weak, people and organizations try to skip local justice and take their cases directly to the Inter-American system.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.