Cubans show a weariness never seen before, especially since Hurricane Ian made landfall in Cuba on September 27, and food, medicine, and electricity have become even more scarce.

After the pandemic and subsequent higher food prices, Cubans are struggling with new levels of poverty, famine, blackouts, and deficient medical care.

The regime has imprisoned over 1,400 people and many are awaiting trial after massive, peaceful demonstrations in Cuba in July 2021. Social unrest has persisted as people increasingly resort to the informal market.

Even those who had previously been comfortable with the regime, as well as law-enforcement agents, are considering leaving the country.

An Impunity Observer researcher has just visited the island to see and hear first-hand from Cubans about their struggles, and to find out how consolidated the Cuban dictatorship seems to be.

He interviewed people from the poorest neighborhoods to the wealthiest—young and old, working people and the unemployed, government sympathizers and opponents, physicians, and law-enforcement agents.

All of them, excluding Cuban activist and writer Ángel Santiesteban, requested anonymity out of fear of reprisal by the Cuban dictatorship.

Hunger and Poverty under Communism

A man in Old Havana approached the Impunity Observer researcher begging for money to buy milk for his son, saying he had to feed him “sugar water.” Independent media outlet Diario de Cuba has reported that malnutrition is an acute problem, particularly in households that do not receive remittances from abroad.

Official media, however, deny malnutrition is rampant in Cuba.

Every Cuban he talked to faces the same challenge. Rich or poor, they cannot get enough food for their families. While some explain they cannot afford to buy it, other common reasons given are the state-imposed ration card and food scarcity. There is almost no milk, meat, or flour on the island.

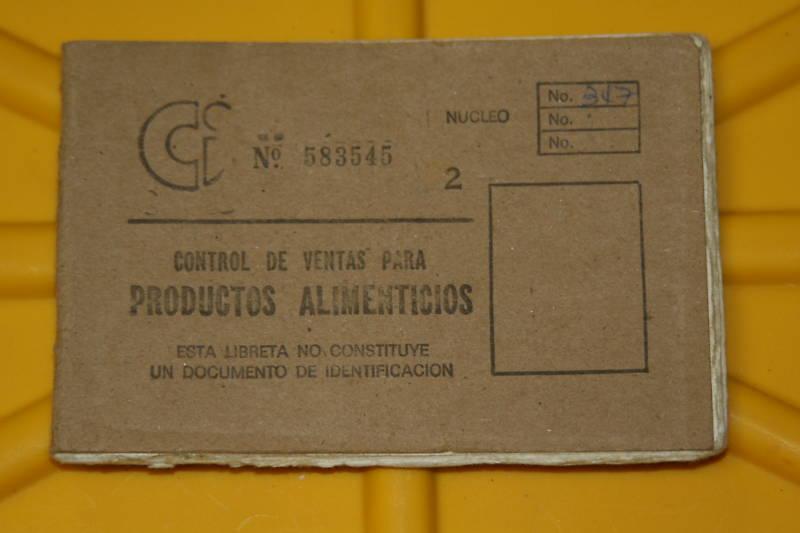

Fidel Castro launched the ration card in 1962 to supposedly ensure monthly access to food for all Cubans. Today, it provides each individual per month with five eggs, a quarter of a chicken, five pounds of rice, a half pound of vegetable oil, 10 ounces of black beans, one box of matches, and one bag of coffee.

Designed as an assistance policy, the ration card provides a modest amount of food that can feed a person for only 12 days at most.

Outside of the Communist Party office in Old Havana, a 65-year-old sympathizer of the dictatorship acknowledged that obtaining food on the island is difficult. He told the Impunity Observer that the problem stems from the US embargo.

However, food was excluded from the embargo in 2001. In fact, from July 2021 to July 2022, US exports to Cuba increased by 31.3 percent, with poultry meat accounting for 86 percent.

Cuban food production is dwindling as well, with farmers placed between a rock and a hard place. Since the Communist Party government favors redistribution, it requires farmers to sell their products to the state at fixed, noncompetitive prices in Cuban pesos. Farmers then go backwards when they buy supplies in currencies from other countries, such as euros or dollars.

The Cuban government has acknowledged, for example, its diminished access to wheat.

Long queues to buy food with the ration card are common. People wait for hours in the streets with no certainty that they will find what they need. Stores frequently run out of food before serving all people waiting in line.

The Impunity Observer witnessed, outside a state-owned store in Vedado, a desperate, weeping middle-aged woman crying: “I can’t buy food for my children.”

Food scarcity is also undermining tourism. The Impunity Observer saw this in early October this year at Hotel Presidente’s restaurant in Vedado, Havana, which offered only two of 11 sandwiches and burgers on its menu because it was out of beef and pork.

Many people said the situation worsened after COVID-19. “Before the pandemic, getting food was a challenge, but now there is simply not enough,” a man in Miramar told the Impunity Observer.

Nonexistent Fairness under Cuban Communism

“I am tired of blackouts! Almost every day, we are without electricity while hotels and the privileged people do not have to suffer this,” a man was screaming in a plaza on Paseo Avenue in Vedado. Four days a week, power goes off for 5–7 hours in Havana.

Worse still, blackouts happen every day for around 12 hours in other provinces such as Matanzas, Pinar del Río, Mayabeque, Holguín, Santiago, Guantánamo, and Camagüey.

Since tourism is an important source of revenue for the Cuban government, hotels—partially owned by the state—do not suffer from blackouts. However, they rely on power generators.

Meanwhile, blackouts are reducing quality and delaying coffee production. People have found debris in their bags of Hello! Coffee—the state-distributed coffee—but officials claim their quality control is working well.

Cubans are not only facing increasing blackouts but also the deterioration and even collapse of their residences. On October 17, a building crumbled in Old Havana and killed a five-year-old infant. Many other cases have been reported.

A 75-year-old mother in Jesús María, Havana, told the Impunity Observer her dorm crumbled two years ago while she was inside. She fell two floors but survived. She cannot afford to repair her house and has been unable to receive state aid. For her, the regime only cares about building new hotels, not helping the people.

As with food and electricity, cement has been scarce in Cuba since 2019, affecting the quality of most buildings in Havana. The regime has acknowledged this but has never proposed a solution.

Antonio Font Carreño, vice president of the development organization PEMENCUB, has shared with Radio Martí that aside from lacking resources, there is no will on the part of officials to solve the construction crisis.

Meanwhile, the regime continues building hotels.

Scarcity Leads to Black Markets

What are Cubans to do in the face of so much scarcity? The communist ideal of the state taking care of the needs of its people has failed.

Cubans’ first option is to resort to the black market—thereby facing disproportionately high prices and risking imprisonment of up to five years.

Likewise, before undergoing a medical procedure, Cuban hospital patients must now provide most supplies that they buy on the black market. The Impunity Observer talked to a medical student at Havana University who is working in a neighborhood hospital. He asserts, for example, that most times patients bring their own mosquito nets if they are being treated for dengue fever. He said, “this also happens with suture threads and needles.”

Cubans say that the state’s medical distributors do not work properly either, so they have to buy their medication to treat blood pressure and thyroid disorders for $200 and $300 more on the black market.

Some of them consider themselves lucky because they have family in the United States that sends them money. Otherwise, they would not be able to afford their medicine.

Multiple people—including elderly citizens—told the Impunity Observer that the local hospitals where they usually have their medical appointments have closed because of insufficient resources and personnel, so they have to seek medical attention further away. Indeed, the doors at the Camilo Cienfuegos International Clinic in Vedado were closed for the entire week the Impunity Observer was in Havana.

Likewise, finding gasoline is a daily challenge. The price of gasoline is 30 Cuban Pesos per liter (US$4.77 per gallon), but only a few filling stations are open. People have to wait in line for almost an hour to fill their fuel tank. Often, they also fill spare gas tanks to have reserves.

Currently, gasoline cannot be bought on the black market because not enough gasoline shipments arrive on the island, and the regime has the exclusive authority to import gasoline. As a result, Cubans usually must find alternative solutions for transportation.

Cubans Fed Up with Disastrous Policies

Even just two years ago, it would have been difficult to imagine Cubans daring to express their discontent on the streets. Nationwide demonstrations are now constant.

The most recent in Havana was on October 1–2—right after Hurricane Ian, when electricity was available only two to three hours per day—had people asking for electricity and freedom.

Almost daily, local media outlets and local individuals are reporting peaceful protests in other provinces outside Havana. In Las Tunas, a city in eastern Cuba, people were on the streets demanding electricity—a problem that has persisted for months now.

Multiple demonstrations erupted on October 13, following power shortages in provinces such as Santiago, Holguín, Mayabeque, Matanzas, and Cienfuegos.

Many Cubans are not willing to risk their livelihoods and any semblance of freedom they might have after watching the police attack demonstrators in some places. They fear jeopardizing their families.

A 47-year-old man in Miramar told the Impunity Observer, “If everyone went out to the demonstrations, I would definitely go too, putting at risk providing for my child—but that never happens.”

Ángel Santiesteban told the Impunity Observer that the reason why people never go to the streets at the same time is because the regime cuts off the internet service in neighborhoods where there are no demonstrations. Thus, the regime isolates the demonstrators, and the neighbors learn about the demonstrations after they have already happened.

The nationwide demonstrations accurately reflect the feelings of Cubans in Havana, though. Ninety-two percent of the 25 people the Impunity Observer spoke with are tired of the circumstances.

They all said it is time for a change, as things have not been working for a while. Every interviewee younger than 40 said he wants to leave or would consider leaving Cuba if he had the opportunity.

A study by Diario de Cuba reports that more than 224,000 Cubans arrived in the United States in 12 months between 2021 and 2022. In other words, almost 600 Cubans arrived daily in the United States to stay. In September 2022, 26,742 Cubans arrived in the United States, which is the highest number since March 2021 when 35,000 Cubans entered.

Censorship Continues to Be Communist Response to Cubans’ Plight

The dictatorship has turned a deaf ear to Cubans’ peaceful demonstrations, responding with undercover agents promoting violence and imprisoning demonstrators.

Police agents dressed as civilians punched 15- and 16-year-old teens who were chanting, “Freedom,” during the October demonstrations on Línea Street.

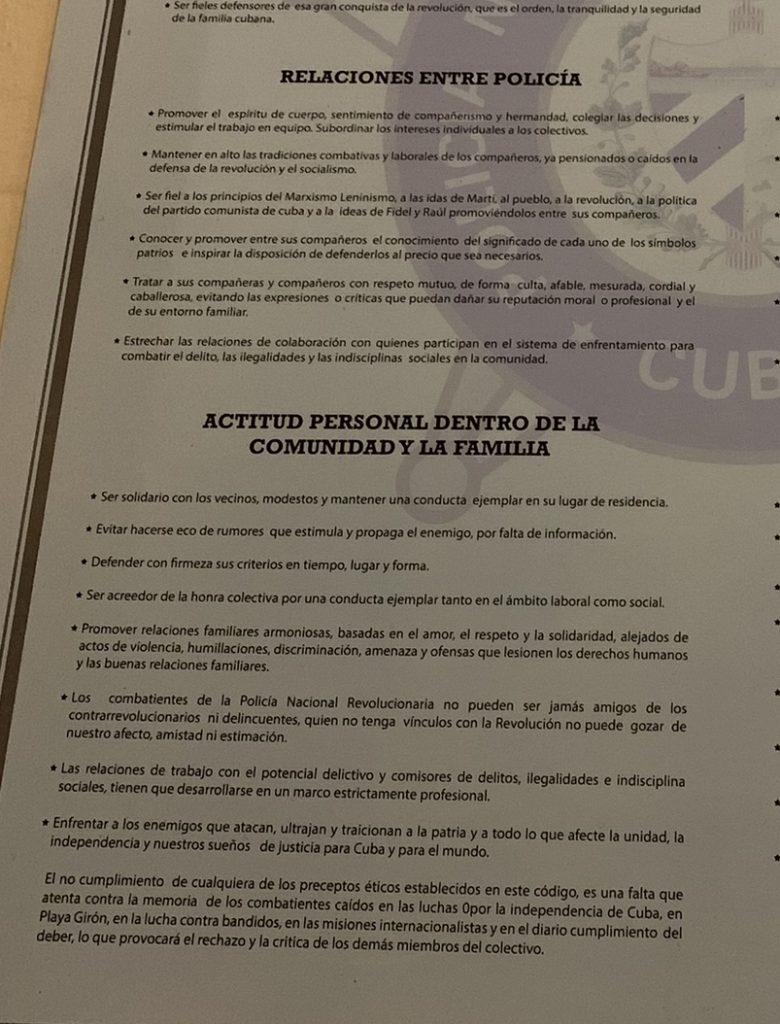

Blind obedience to communist ideals by police is clearly spelled out on a sign in their Old Havana and Central Havana headquarters which says, “Members of the National Revolutionary Police are never friends of insurgents and criminals. Anyone without ties to the revolution will not enjoy our affection, friendship, or appreciation.”

No change appears to be coming from the rulers who cling to power. No improvement is in sight for Cubans, rich or poor. The code of ethics of the police represents well the unchanging communist ideas still enforced by the Cuban government:

“Be faithful to the principles of Marxism-Leninism, to Martí’s ideas, to the people, to the revolution, to the policies of the Cuban Communist Party, to Fidel and Raúl’s ideas.”

However, Cubans are fed up like never before and increasingly expressing their discontent. A middle-aged man approached the Impunity Observer researcher in Old Havana asserting, “Look around you. This is misery. This is poverty. We need to change the system.”

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.