Key Findings

- In 2008, one year after President Rafael Correa took office, corrosive capital from China began impregnating Ecuadorian institutions. It conditioned the state to purchase from and contract directly with China’s state-owned companies.

- Between 2015 and 2019, China constructed over 70 percent of Ecuador’s infrastructure projects in strategic sectors such as energy, oil, and mining. Many of these have involved public-funds embezzlement, influence peddling, and shoddy construction.

- The Coca Codo Sinclair dam, built by China’s state-owned Sinohydro in 2016, has over 7,000 cracks. These have impeded its full operation for the past three years.

- The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has rejected accusations of corruption via the investment. The regime claims to have promoted transparency and strong institutions.

- Researchers from the Foundation for Citizenship and Development (FCD)—those who documented the corruption cases—have dismissed the CCP response and claim it neither presented valid counterarguments nor addressed the specific cases.

Introduction

Ecuadorian public institutions—along with those in Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela—have become a chief destination in Latin America for loans from Chinese state banks. Local NGOs focused on government transparency, however, are revealing problematic strings and consequences that come with these loans. They offer the Chinese side more than exclusively a business opportunity.

The rise in Chinese investment in Ecuador started after socialist President Rafael Correa took office in 2007. In 2008, reported Chinese investment in Ecuador—both credit and equity—reached $2.2 billion, and CCP Conference Chairman Jia Qingling signed three cooperation agreements for over $52 million. The agreements included loans to Ecuador and purchases of Chinese-made planes for the Ecuadorian Air Force.

Between 2010 and 2019, Ecuador received over $16 billion from Chinese banks. More than 80 percent of Chinese loans granted to Ecuador have an interest rate between 6.25 and 7.91 percent. This is around 50 percent higher than those typically offered to developing countries by international organizations such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. The elevated rates partially stem from a high national risk premium. However, the rates also pose the question: why did Ecuadorian officials take on such costly credit?

An investigation by FCD, published in September 2022, identified Chinese infrastructure financing in Ecuador’s strategic sectors such as oil, mining, and energy. The Chinese investment deals, which began in 2007, have failed to accomplish their stated goal of “exporting clean energy to the rest of the region.” Instead of exporting clean energy, Ecuador will spend over $400 million in 2023 to import energy from Colombia, as Ecuadorian power plants are working at 41 percent of their full capacity.

The many CCP-backed deals have lacked transparency and been associated with bribery of officials. The greasing of the wheels has included prominent corruption scandals such as the Coca Codo Sinclair dam. It is a $3 billion project that has failed to work at full capacity for the five years since its opening. FCD has described Chinese infrastructure projects in Ecuador—such as hydroelectric plants and oil and mining exploration concessions—as “corrosive capital.”

The Corrosion of Weak Institutions

In 2015, the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE)—a US institution that supports democracy favorable to the private sector—coined the term corrosive capital. It refers to “financing that lacks transparency, accountability, and market orientation flowing from authoritarian regimes into new and developing democracies.” Corrosive capital reaches countries through foreign direct investment, portfolio investments, financial aid, infrastructure projects, and commercial loans.

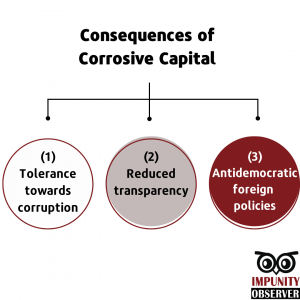

A wide range of consequences stem from corrosive capital: (1) tolerance towards corrupt capital sources, (2) reduced transparency, and (3) foreign policies that benefit undemocratic countries.

The countries that receive corrosive capital usually exhibit two key conditions: weak institutions and a lack of financing opportunities.

“One of the main challenges with corrosive capital is that, apart from weakening crucial institutions in the country, it prevents institutions from consolidating, garnering trust, and developing,” Andrés Lozano, coauthor of the FCD investigation, told the Impunity Observer.

Why Ecuador Is Vulnerable

By 2008, Ecuador had acquired the two conditions for corrosive capital. After starting the century with a political crisis and three different presidents in three years, Ecuadorian institutions remained weak. In 2008, Ecuadorian elected officials also wanted more financing opportunities to bankroll Correa’s “citizen revolution.” His proudly socialist plan required fiscal deficits to fund infrastructure projects, such as new airports, and new social programs, such as elderly care and food provision for children.

Ecuador’s institutions continue to be weak, according to the Institutions’ Quality Index of Latin America’s Liberal Network (RELIAL). It analyzes factors such as the rule of law, freedom of expression, corruption, and economic freedom. Despite improvement in Ecuador’s scores in 2022—climbing from 129th position in 2021 to 121st in 2022—it is still lower than neighboring Colombia and Peru, which are 87th and 71st, respectively.

By the end of 2008, during Correa’s first tenure, the Ecuadorian government announced a default on 91 percent of its external debt, declaring it “illegitimate and illegal.” Correa even called the bondholders “real monsters.” As a consequence, Ecuador found fewer willing lenders and more costly terms.

To obtain funding for his policy plan, the Correa administration approached a series of ideological allies such as Bolivia, China, Cuba, and Nicaragua for money.

Money Infects Then Flows Back to China

Between 2015 and 2019, the Ecuadorian state granted Chinese companies over 70 percent of the largest contracts in the oil, mining, and hydroelectric sectors—many of which are involved in corruption cases such as influence peddling and public-funds embezzlement.

The FCD investigation states: “Chinese loans granted to Ecuador for projects in strategic sectors had specific clauses that allowed more Chinese companies into Ecuadorian markets.” Instead of hiring companies to construct infrastructure through procurement processes, Ecuadorian officials directly hired Chinese companies, which have avoided competition with local or international firms. This tit for tat of loans going straight back into the pockets of Chinese firms sweetened the deal for the CCP and likely explains why the party was willing to direct funds to a recently defaulted debtor.

Leonardo Gómez, coauthor of the FCD investigation, told the Impunity Observer that nine out of 10 Chinese investment projects they analyzed had at least one case of corruption. The corruption cases included (1) bribery, (2) public-funds embezzlement, and (3) influence peddling.

For example, the Coca-Codo Sinclair dam in the Napo province of the Ecuadorian Amazon has failed to work at full capacity since its opening in 2016. The Comptroller’s Office found over 7,000 cracks in the dam that cost $3.2 billion. It was built by the CCP-backed Sinohydro, and its funding came mainly from China’s state-owned Exim Bank.

Several Ecuadorian officials involved in the dam’s construction have served jail time due to bribery charges. Former Vice President Jorge Glas and Energy Minister Alecksey Mosquera are still facing public-funds embezzlement charges from the Ecuadorian Comptroller’s Office.

There are many other examples of corrosive capital in Ecuador’s strategic sectors. A few notable ones include the Paute Sopladora dam, the Minas San Francisco dam, and the Santa Elena aqueduct.

How the CCP Defends Its Actions

China’s Embassy in Ecuador has not remained idle in the face of criticism, and on October 18, 2022, it rejected the investigation in a four-page press release. CCP officials described the FCD account as “defamatory statements” and noted that “no one forced Ecuador to sign the cooperation agreements.”

CCP officials also contend China’s Exim Bank and Development Bank have supported Ecuador through COVID-19 lockdowns, despite FCD accusations to the contrary. Similarly, the CCP release noted the importance of Chinese investment in developing Ecuador’s infrastructure.

Finally, CCP officials claim to have always been on the side of transparency, and there is now detailed data available online related to Chinese loans in Ecuador. Whether all the numbers are accurate, however, remains disputed.

#Importante | Emitimos nuestro Comunicado Oficial respecto a los difamatorios comentarios sobre las inversiones y el financiamiento de China en el informe de @FCD_Ecuador. pic.twitter.com/rnldvWPhO4

— Embajada de la República Popular China en Ecuador (@EmbajadaChinaEc) October 18, 2022

Gómez and Lozano, in an exclusive interview with the Impunity Observer, replied to the CCP statement. Lozano clarified that FCD’s investigation focused on corrosive capital from China because it is the most prominent example in Ecuador. The investigation, however, did not seek to undermine or dissuade all Chinese (or foreign) investment in the country.

Gómez and Lozano contend the CCP statement fails to refute the investigation. The authors actually agree, though, with the first argument in the statement. Gómez blames the Correa administration for approaching China for money and accepting harmful terms. Regarding the statement’s second argument, Gómez responded: “It is true that China helped Ecuador in times of need during the pandemic, but its conditions remain to be examined.”

Gómez also responded to the statement regarding China’s alleged transparency. “They talk about transparency. However, the data about Chinese loans and investment only became available after the Correa administration ended, years after the agreements were already put in place.” Lozano and Gómez agreed they are questioning the forms and the costs for Ecuador, not denying that Ecuador has in some ways benefited from Chinese investment.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.