Key Findings:

- The Cuban regime and the investment fund CRF1 Limited are waiting for the judge’s decision in a lawsuit before London’s High Court over a $72 million claim against the island. The decision will take from two to four months, and it could further open the door to claims of $2 billion or more.

- The judge will not only settle Cuba’s payment but also the methods for payment in case it rules in favor of CRF1’s claim to Cuba’s sovereign debt.

- John Kavulich, head of the US-Cuba Trade & Economic Council, contends that even a loss in the trial could be positive for the Cuban regime if officials react proactively by restructuring the debt.

- If Cuba loses the trial and dictatorship officials fail to reach an agreement with the fund, the court could decide to seize the regime’s goods and freeze its bank accounts in other countries.

Overview

CRF1, an investment fund registered in the Cayman Islands that belongs to the London Club, filed a lawsuit in February 2020 against Cuba and Cuba’s National Bank (BNC) for an unpaid debt acquired during the Fidel Castro dictatorship. The trial took place in London’s High Court between January 23 and February 2, 2023. UK Judge Sara Cockerill’s decision, however, is expected to take months, according to France 24. After Cockerill’s verdict, both parties can appeal the decision, so the final sentence could drag on for more than one year.

CRF1 acquired more than $1 billion of Cuba’s sovereign debt in 2019 for an undisclosed value from the Chinese ICBC Standard Bank. This trial focuses on settling CRF1’s demand for $72 million for two specific loans. The trial will also determine whether CRF1 has grounds to pursue the broader $1 billion debt.

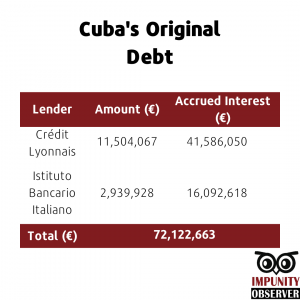

The Dutch bank Crédit Lyonnais and the Italian bank Istituto Bancario Italiano originally granted the Republic of Cuba loans between 1980 and 1985 for over $14 million. With the accrued interest of both loans, defaulted on in 1986, the value Cuba owes adds up to over $72 million.

David Charters, chairman of CRF1, claimed in 2020, when CFR1 first filed the lawsuit, that the only way to halt the legal process was to reach a “fair and equitable agreement.” The decision is now in the hands of the UK judge since the parties failed to reach a deal. Charters said that going through with the legal process was “unattractive for CFR1,” but since it was the only way to get things done “it is a route they had to take.”

What the Trial Portends

Cuba is facing its worst economic crisis since the beginning of the century. Among other challenges, Cubans are struggling with constant electricity blackouts, scarce medicine, food, and fuel, and collapsing buildings.

Further, its main economic and ideological allies—China, Russia, and Venezuela—are also going through rough times economically. Russia, for example, is focused on its ongoing invasion of Ukraine and is having a tough time delivering aid to Cuba.

Apart from spending over $3 million on lawyers since the process began in 2020, hiring UK-based PCB Byrne LLP, Cuba might have to pay $72 million in principal and interest from the 1980s loans. A CNBC report anticipates Cuba’s outstanding sovereign debt of $7 billion becoming vulnerable to further lawsuits. Cuba’s annual GDP is $107 billion.

John Kavulich, head of the US-Cuba Trade & Economic Council, told the Impunity Observer that “losing the lawsuit would increase the focus on Cuba about what it owes, to whom it owes, and that it does not repay creditors—commercial and government.”

Losing the lawsuit could also end up benefiting the regime, contends Kavulich. This could only happen if the dictatorship “were to immediately engage with CRF1 and construct a repayment process that it could maintain. A successful negotiation with CRF1 would begin to recreate an atmosphere whereby companies might again look positively at the country.”

Cuba’s Diary, an independent local news outlet, has reported that a loss in the lawsuit would represent “a second embargo,” as the UK High Court could proceed to seize Cuban goods overseas and freeze the regime’s bank accounts. Cuba would not be able to borrow money from international markets until the country settled the debt.

Depending on the outcome, lawsuits are likely to emerge from other creditors, whether they belong to the London Club or not. These creditors are closely watching the case, especially since the Castrista regime still owes over $2.5 billion to the Paris Club despite reaching an agreement in 2015 that forgave $8.5 billion.

“The message to financial institutions and companies that are watching the trial is to avoid Cuba,” contends Kavulich.

The Dictatorship’s Side of the Story

The Castrista dictatorship’s main argument in London’s High Court was that “CRF1 has never been a creditor of Cuba or the BNC.” Cuban central-bank officials expressed this in a public statement. Cuban officials—in dictatorship media and in the trial—have described CRF1 as a “vulture fund.” According to Investopedia, “a vulture fund invests in assets whose prices have been severely depressed in the market.” In response to the description, CRF1 Chairman Charters said: “Characterizing us as a vulture fund is a gross misrepresentation.”

Apart from Cuba’s argument that CRF1 has never been its creditor, dictatorship officials have also accused CRF1 of bribing former BNC’s Operations Director Raúl Olivera in 2019, when obtaining legal documents for their debt acquisition. Sentenced to 13 years in prison in 2021 due to alleged bribes, Olivera appeared before London’s High Court remotely explicitly claiming CRF1 bribed him to obtain the contracts that allowed CRF1 to acquire Cuba’s debt. He also asserted in court that he breached his authority as BNC’s operations director when giving the contracts to CRF1.

In response to Cuba’s accusations of bribing Olivera, CRF1 declared that Cuban officials created this story to elude their responsibility for the $72 million debt. Near the end of the trial, the defendants withdrew the bribe arguments for unknown reasons.

What CRF1 Offered the Dictatorship

Before CRF1 filed the lawsuit, the investment fund reached out to the Cuban dictatorship and attempted to reach an agreement. One of the options included a debt-for-equity swap, common in debt-restructuring deals in financially unstable countries. A debt-for-equity swap refers to the creditor converting the debt into equity in a state-owned company.

In this swap, CRF1 would have received a concession or ownership of dictatorship-owned companies such as airports, hotels, or ports. CRF1 would have received all or most of the revenues from these assets, which would have allowed Cuba and the fund to reach an agreement and avoid trial. Further details on the investment fund’s proposals remain undisclosed.

According to Charters, accepting the restructuring deal offer would have “granted Cuba access to international financial markets after years of being excluded.” Other lenders would have considered the regime open for collaboration if they managed to reach a debt agreement, CRF1 expressed in a public statement.

As it stands the Cuban regime has been unwilling to work with CRF1 or let go of any state-enterprise income. Perhaps regime officials believe they can better weather the storm of a legal ruling than make good on the nation’s debts. Regime officials appear unconcerned about a lack of access to further credit, even as the nation is entering an era that could justify it, along with market liberalization to address the economic crisis.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.