Key Findings

- In June 2021, then President Iván Duque signed the Energy Transition Law. The legislation contemplated (1) a gradual decline of fossil-fuel production, (2) a fund from oil and mining royalties to finance the transition, and (3) tax perks to stimulate unconventional renewables: wind, solar, geothermal, and hydrogen.

- During the Conference of the Parties on Climate Change in Dubai (COP28), held in November 2023, President Gustavo Petro made available for participation a $34 billion investment portfolio for “climate action” to accelerate the transition in Colombia. He also announced that the government would grant no more oil or coal exploration licenses.

- In December 2023, however, Petro allied with dictator Nicolás Maduro to exploit oil and gas in Venezuela through a partnership between Colombia’s oil company Ecopetrol and Venezuela’s PDVSA. The agreement contemplates importing oil and gas from Venezuela, starting from 2025, if Colombia runs out of domestic energy.

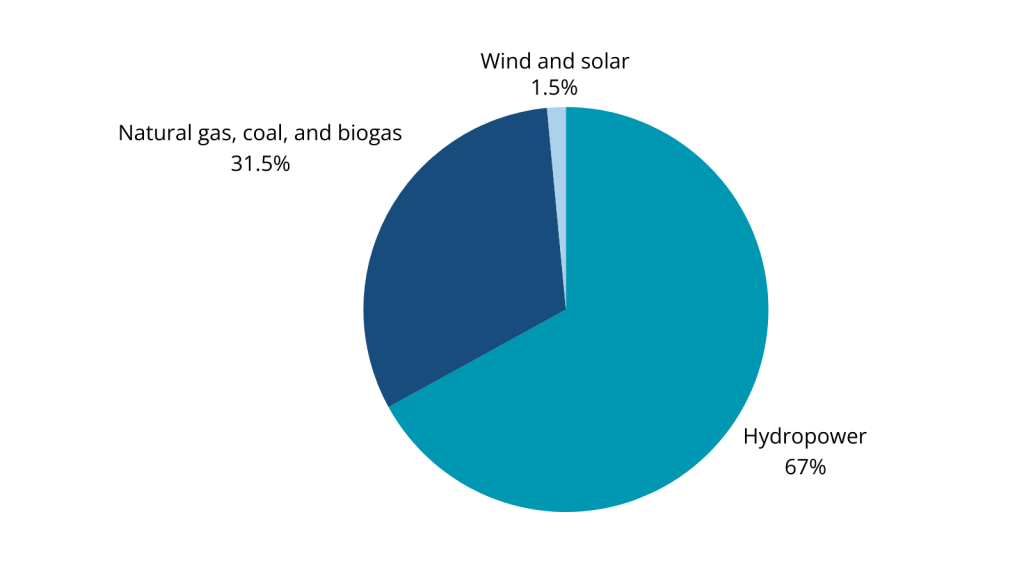

- In 2022, the last year for which there is available data, the major sources of Colombia’s energy consumption are hydropower (67 percent) and natural gas, coal, and biogas (31.5 percent). Solar and wind power account for 1.4 percent and 0.1 percent, respectively.

- The Petro administration, in office since August 2022, is working on a road map to deploy its energy transition plan. The first version, released in April 2023, did not include enough fossil-fuel reserves for energy security. The government presented a newer version in late 2023 and requested feedback from the civil society. The Ministry of Energy and Mines is still working on the final version of the road map.

Introduction

Colombian President Gustavo Petro made energy transition one of his 2022 presidential campaign’s flagship policies. He pledged to replace fossil fuels with renewables and turn Ecopetrol, the fourth largest oil company in Latin America, into the region’s most influential green-energy firm. In the meantime, however, the lack of legal certainty has made his policy typical of populist pledges from Latin American caudillos.

In 2023, Ecopetrol reported profits down 43 percent year over year, and oil, gas, and coal production levels in 2023 were as low as those of 2020. However, fossil fuels account for 30 percent of Colombia’s exports, and oil accounts for 13 percent of government revenues. Not without irony, the Energy Transition Law (2099 Law) expected to finance the transition with and depended on oil and coal royalties.

Watch on YouTube | Listen on Apple Podcasts | Watch on Bitchute

Nevertheless, Petro has stifled those industries by announcing the government will not grant more oil or coal exploration licenses. For him, tourism and industrialized agriculture could replace the revenues derived from fossil fuels, although such scaling is challenging in short order.

The Colombian Oil, Gas, and Energy Chamber (CAMPETROL) has estimated halting new oil and gas production will reduce contributions to the public budget by $4.8 billion through 2026 and by $24.5 billion through 2032. CAMPETROL has also mentioned that shifting 45 percent of energy production to unconventional renewables (not including hydropower) by 2050 would cost $532 billion in lost economic activity.

This investigation examines the state and impact of the energy transition in Colombia and the feasibility of the governmental plan to replace energy and revenues from the oil and coal industries. The Petro administration has turned a strategic economic policy—to tackle global economic challenges—into a ploy to deepen government intervention and finance the Venezuelan dictatorship.

La transición energética implica un fuerte componente de reconversión laboral y empresarial. El plan de desarrollo lo contempla pero su aplicación debe comenzar ya.

Pasar a energías limpias va de la mano de los trabajadores y empresarios hoy ubicados en las energías fósiles.

— Gustavo Petro (@petrogustavo) March 16, 2023

Energy Transition Advances at Snail’s Pace

In June 2023, the World Economic Forum (WEF) released the most recent Energy Transition Index. Falling back 10 positions from the previous year, Colombia was 39th out of the 120 assessed countries (from 29th in 2022) and sixth in the Latin American ranking.

Unconventional renewables—such as wind, solar, geothermal, and hydrogen—remain insignificant in Colombia. For domestic consumption, in 2022—the last year for which there is available data—the major sources are hydropower (67 percent) and natural gas, coal, and biogas (31.5 percent). Solar and wind power only account for 1.4 percent and 0.1 percent, respectively. Further, around 80 percent of the exported energy comes from fossil fuels.

Colombia’s Energy Matrix (2022)

Germán Corredor, former director of the renewables association SER Colombia, claims a handful of projects were in motion when Petro took office. These projects are likely to start operating in late 2024 with a capacity of 3,000 megawatts (MW). As of November 2022, the solar and wind power installed capacity was 1,365 MW, and the overall national energy capacity was 17,326 MW.

Corredor argues the energy transition needs at least 15 years, rather than a grandiose year or two. “It depends on the governmental impetus, its signals, and the incentives it offers for the development of this effort,” he said to Bloomberg Línea.

The Petro administration, however, has deterred investment. Corredor mentioned: “We estimate there is around $3 billion in private capital ready to invest in renewable energy, but uncertainty makes investors pause and analyze scenarios.” For him, companies should invest not only in infrastructure for renewables but also in transmission and distribution, smart metering, electric vehicles, charging stations, and workforce training.

Similarly, American Enterprises Council Executive Director Ricardo Triana told Forbes Colombia the energy transition should be “reliable and well structured enough to contribute to the economy without risking the country’s security of supply.” For him, the government must boost legal certainty, cut red tape, improve infrastructure, and apply tax incentives to attract more foreign investment.

Digital outlet Cambio Colombia reported, in February 2024, that Colombia has 66 projects ongoing to build solar panels that were expected to start operations this year. However, 44 of them are stalled due to pending permits and approvals. SER Colombia has stated that permits and licenses could take between three and six years, while the actual building of energy plants takes about nine months.

To streamline procedures and provide guidelines for implementing the energy transition, the Petro administration has offered to develop a road map. However, the first version, released in April 2023, did not entail enough fossil-fuel reserves for energy security. The government submitted a newer version for civil-society scrutiny in late 2023. The Ministry of Energy and Mines is still working on the final version of the road map despite the deadline being February 2024.

In the meantime, during the Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP28) in Dubai, held in November 2023, Petro announced the creation of a $34 billion investment portfolio to accelerate energy transition and promote climate action in Colombia through 2026. The portfolio contemplates 14 projects to fight climate change, and $14.5 billion is slated for decarbonization of the electric system.

This amount, however, will only give an initial boost. The World Bank estimates that to achieve decarbonization Colombia needs to invest 1.5 percent of its GDP until 2030 and 1.1 percent until 2050. Former Finance Minister Mauricio Cárdenas has told La República in Colombia that a genuine energy transition would imply investment of around 7 percent of the country’s GDP until 2050. As of 2022, Colombian GDP was $343.6 billion.

Energy Transition as a Smokescreen

During the COP28, Petro also announced he had ruled out awarding new oil and coal exploration contracts: “The transition to clean energy sources is not simply an option; it is an urgent necessity to which Colombia seeks to respond.”

“[The energy transition’s] arrival in this group of pioneering nations strengthens our collective position and demonstrates growing diplomatic support for a negotiating mandate for this fossil-fuel treaty. With Colombia, we have just taken one more step towards a future free from oil, gas, and coal.”

However, one month later, Petro met with Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro and agreed to exploit oil and gas in the neighboring country through a partnership between Ecopetrol and Venezuela’s oil company PDVSA. The agreement contemplates importing oil and gas from Venezuela, starting from 2025, if Colombia runs out of energy supply (which seems certain). In March 2024, Ecopetrol’s chairman Ricardo Roa announced that Colombia could face an estimated 17 percent fossil-fuel shortage in 2025.

The agreement with Venezuela is valid until 2027, and it was signed during the six-month window in which the United States had lifted the sanctions on PDVSA, although US officials could extend this period (which is set to expire in May). “This decision was made as sanctions were lifted. If they were to exist again, we would abstain from doing transfers and transactions,” Roa explained.

To justify his decision, Petro tweeted: “Colombia has imported gas for years, and it does so at very high prices. That imported gas substantially influences the high cost of electricity sold on the market. Importation is done by a powerful economic group.”

In addition to taking advantage of the sanctions relief on Venezuela to justify financial transfers from the Petro administration to the dictatorship, the Colombian president is resorting to an uncertain source of fossil fuels to deal with energy supply in 2025.

Can Fossil Fuels Finance Their Own Demise?

The energy transition in Colombia is purportedly in response to evolving global demand. As the world explores alternatives to fossil fuels, however, they remain integral to the Colombian economy.

Colombia is the fifth-largest coal exporter in the world. China, Japan, Brazil, and Turkey are the main destinations for Colombian coal. In 2017, 2018, and 2019, Colombia exported around 80 million tonnes per year at an average price of $90 per tonne. The coal sector accounted for 2 percent of GDP. Given the impact of COVID-19 and limits on production and importation, it only accounted for 0.7 percent in 2020. The production was 49 million tonnes, and the price was around $50 per tonne.

As the global economy returned to normal in 2021, coal demand and the market price increased—reaching $298 per tonne in October. However, the production capacity of Colombian companies was not enough to satisfy the growing demand for coal. Their market share declined, with almost no exports to Europe.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, the coal price soared to over $440 per tonne, and European countries replaced part of their Russian coal supplies with Colombian coal. That year, Colombian coal exports to Europe increased by 54 percent.

Coal exports were worth $12.3 billion in 2022, an increase of 117 percent from the past year. That year, the coal sector contributed more than $3 billion to public coffers through taxes and royalties. After the boom, Colombia exported 56 million tonnes of coal at an average price of $200 per tonne in 2023. It accounted for one percent of the country’s GDP.

Oil production accounts for around 3 percent of GDP, but it is declining. From 2022 to 2023, both oil exports and foreign direct investment for that sector decreased by 15 percent.

Since oil companies operating in Colombia cannot drill more wells for exploration, more than 19,000 jobs disappeared in 2023. Without further exploration, the International Energy Agency estimates oil production in Colombia could fall from 777,016 daily barrels—reported in 2023—to 620,000 barrels per day in 2028.

Ecopetrol Already Faltering

Ecopetrol is a mixed company owned by the Colombian state (88.5 percent), pension funds (5 percent), and private investors (6.5 percent). As the largest oil company in the country, uncertainty about the future of fossil fuels and the energy transition has harmed its performance.

Although Petro has proposed to turn Ecopetrol into a green-energy giant, the company is struggling to maintain profitability. For Rafael Nieto, former justice minister in Colombia, it is a no-brainer: “An oil company that does not seek to expand its reserves loses its value.”

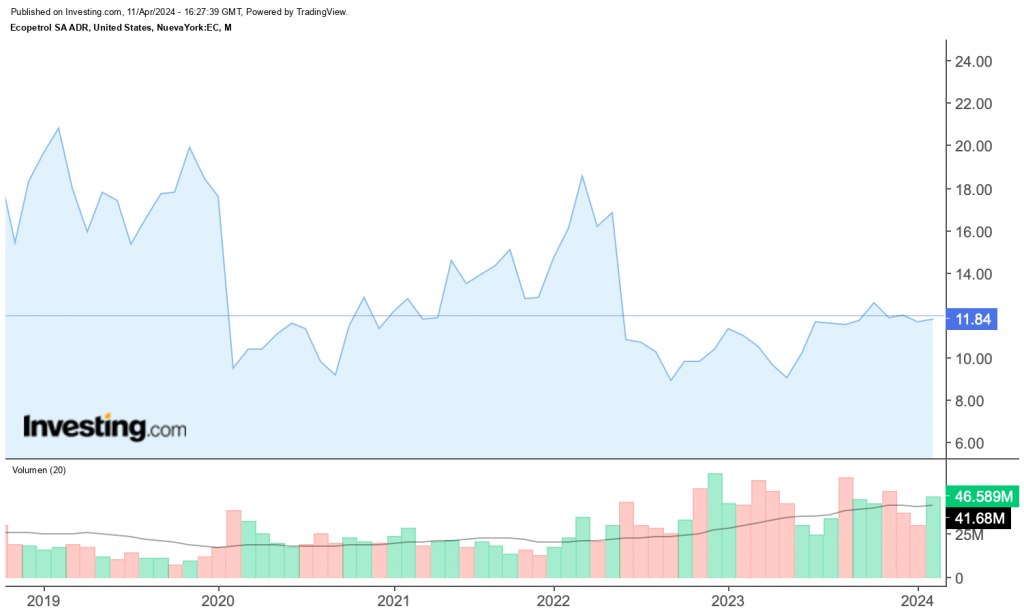

Listed on the Bogotá and New York stock exchanges, Ecopetrol’s stocks have lost one-third of their value in the last two years. From trading on Wall Street at $19.81 on March 1, 2022, the stocks were trading at $11.80, on March 1, 2024.

Ecopetrol’s Stock Price (2019–2024)

Ecopetrol has also gone through a governance crisis, as the Petro administration has interfered. In October 2022, Ecopetrol held an extraordinary assembly to change the board. In March 2023, the new board ousted Felipe Bayón, who had been the chairman since 2017. One month later, the board elected Ricardo Roa as the new chairman. He has had a 25-year career in the energy sector but scant experience with oil.

In early 2024, a broad shareholder group sent a letter to Roa asking him to leave: “You never had enough qualifications to be Ecopetrol’s chairman.” The letter came in response to an audit by the Control Risks global consultancy. The audit sought “to impede managers from acting against stakeholders’ interests—in this case, those of Colombian citizens, the more than 260,000 stockholders, and the more than 12,000 pension holders.”

As a result, on March 22, Ecopetrol’s general assembly chose a new board: five were new members and four were incumbents. “Ecopetrol needs to be protected from being run as a political exercise,” Bayón told the Financial Times. “It’s been politicized. Independence needs to be respected, and it needs to be run like a business.”

En lugar de intervenir las EPS deberían intervenir @ECOPETROL_SA:

1-La junta directiva es ilegítima.

2-Cambiaron el objeto social sin control Constitucional de Integración Vertical.

3-La Empresa perdería su participación en la bolsa de Nueva York por venderle a Venezuela

🧵 https://t.co/N3mV7WtY49— Luis Carlos Orejarena (@lorejarena) April 11, 2024

Transition Is Newspeak for Nationalization

In February 2024, the Ministry of Energy and Mines released on its website a draft bill to forbid coal exploration and exploitation projects. The entity requested citizens contribute their opinions before submitting the final version to Congress.

This makes official what Petro has already announced in international conferences. The draft bill also seeks to enable expropriations of mining assets, reorienting their usage to the energy and industrial transformation.

If an energy transition were the honest objective of the Petro administration, it could collaborate with the likes of Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay. They are further down the path than Colombia.

Uruguay, for instance, managed to decarbonize all its energy production by 2023. Via relatively free energy production, Uruguay spent 3 percent of its GDP per year on an energy transition and attracted more than $8 billion in private capital during the last decade.

Leaning on the Venezuelan dictatorship, which ruined a thriving oil sector, infers other ideological motives, notably a quest for nationalization.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.