The Barack Obama administration and the United Nations are colluding to apply pressure on Guatemala to further an agenda far beyond the UN mandate, redolent of the same Yankee domineering Obama has previously said he wants to end.

The instrument Obama and the United Nations are wielding here is the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), which has been operating since 2007. The CICIG’s self-described mission is “to promote accountability and strengthen the rule of law.”

The CICIG says it targets “illegal security groups and clandestine security structures.” These are groups that “affect the Guatemalan people’s enjoyment and exercise of their fundamental human rights, and have direct or indirect links to state agents or the ability to block judicial actions related to their illegal activities.”

According to Secretary of State John Kerry, the United States has contributed more than US$25 million to the CICIG and is “committed to continuing to fund and support” it. Kerry explained: “Through this commission, Guatemala can send an unequivocal message that no one stands above the law.”

Bluntly speaking, the CICIG is an extraterritorial agency that has acquired the ability to act with the force of law in Guatemala, while answering to no one in the country. It answers, rather, to the United Nations and to a coalition of powers led by the Obama administration.

Washington Deaf to Corruption

The CICIG has been up for renewal in 2015. Until recently, President Otto Pérez Molina had been resisting renewal on grounds that the CICIG’s presence is an affront to Guatemala’s sovereignty. Earlier this year, however, the Obama administration announced a $1 billion aid package for Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, which Vice President Joe Biden peddled in two visits to Guatemala. According to several reports, aid was contingent on renewal of the CICIG’s mandate in Guatemala.

Then, last month — April 16, 2015 — CICIG Commissioner Velásquez announced that, pursuant to an eight-month investigation, the CICIG and Guatemala’s Justice Ministry had obtained arrest warrants against 22 persons alleged to be part of a criminal conspiracy in contraband customs operations. One of the indicted persons, and one of two from the group who gave prosecutors the slip, was Juan Carlos Monzón, private secretary to Vice President Roxana Baldetti.

Almost immediately, Pérez acceded and renewed the CICIG’s mandate for another two years. Then on May 8, Baldetti resigned the vice presidency; she is under a court order not to leave the country.

It is doubtful that such a criminal conspiracy could have existed without at least tacit approval, and probably more, from the highest levels.

Guatemalans have wondered aloud why the CICIG investigation didn’t include their vice president and president, and they have demonstrated, calling for the resignations of those officials.

Even so, US Ambassador Todd Robinson issued a statement a week after the CICIG renewal praising President Pérez’s “leadership in the fight against organized crime and impunity.” The ambassador also said that Washington looks forward to working with the CICIG “to strengthen the institutions of public order that are necessary for the prosperity of the Guatemalan people.”

Two weeks later, on the same day Baldetti resigned, the State Department issued a statement about the resignation, a notably rapid response, publicly encouraging President Pérez “to work closely with” the CICIG.

Spearing Guatemalan Sovereignty

The work of the CICIG, however, offers a remedy in the shape of a pitchfork. Of the three prongs, the most obvious is the case of the contraband ring and others like it, where the CICIG is intervening beyond the limits of its mandate. The contraband ring is a case of theft pure and simple — far distant from the acts of “illegal security groups” which might harm or threaten the “fundamental human rights” of Guatemalans.

Indeed, by getting into Guatemala’s business against the terms of its own mandate, the CICIG actually does what it accuses others of doing: it degrades the nation’s sovereignty.

The second prong of the CICIG’s pitchfork is its habit of acting against the law even when it works in matters apparently consistent with its mandate. A clear example is the case of Erwin Sperisen, a former police chief who is now serving time in a Swiss jail, for actions he purportedly undertook to quell a Guatemalan prison riot in 2006. Sperisen, who has dual Swiss-Guatemalan citizenship, was pursued by the CICIG and arrested in Geneva.

With the CICIG’s agency, the evidence against Sperisen was transmitted from Guatemala to the Swiss court, which accepted it without allowing any rebuttal by the defense.

The chief witness never traveled to Switzerland and only testified via a written statement engineered by the CICIG — a procedure that would be illegal under Guatemalan law.

Sperisen has had his right to due process violated by the CICIG’s operations, and that’s bad enough. But the entire Guatemalan people are having their rights compromised by the CICIG. That is the central prong of the pitchfork: a violation of rights that goes completely unseen, except by its victims.

The CICIG regularly fails to investigate illegal groups that affect the human rights of large numbers of rural peasants. The irony of the situation is that these illegal gangs refer to themselves as human-rights groups — and the United Nations, including the CICIG, compounds this irony by protecting those groups against further scrutiny.

In the words of Guatemala’s former attorney general Claudia Paz y Paz, whose regime made possible a dramatic expansion of these gangsters across Guatemala, the groups must receive “special consideration” — at the United Nation’s and the CICIG’s behest.

Here Come the Feds

In January 2015, self-identified “human-rights” and “indigenous” groups in San Pablo, San Marcos province, destroyed property at the site of a proposed hydroelectric plant. They kidnapped and tortured Casimiro Pérez, a local peasant who had filed criminal complaints against four of the leaders. Various peasants have denounced the illegal, coercive measures that these groups use to subjugate them and force them to commit crimes in support of their agenda, which are then portrayed to the public as spontaneous and voluntary.

A member of our nonprofit group, the Liga Pro-Patria, reported these charges to the CICIG, saying that law-enforcement authorities are taking no significant action to protect the rural populations from the groups, making them into clandestine security groups operating with government complicity.

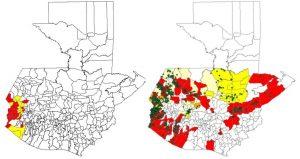

The spread of these groups from an enclave in western Guatemala throughout the entire country can be instantly seen in two images, one for 2010 and the other for 2014.

These dates coincide precisely with Attorney General Paz y Paz’s regime, which had the active, wholehearted support of the Obama administration as well as of the United Nations.

Six weeks after receiving the Liga Pro-Patria report, the CICIG responded that the matter of the human-rights groups is not among its priorities. This is not just a case of fiddling while Rome burns; this is a case of the fiddler burning Rome.

What are the broader ramifications of these maneuvers? US political consultants Dick Morris and Eileen McGann have analyzed the general issue in their books Power Grab and Here Come the Black Helicopters. With detailed examples, Morris and McGann show how President Obama and the Democratic Party have undermined the US Constitution and attempted to use the United Nation to achieve government control in areas that the US Constitution wouldn’t otherwise permit.

Recent US policy in Guatemala, among other areas, looks like a proving ground for those policies, which are presently much easier to implement here than they are in the United States. But make no mistake: if the pitchfork continues to work in Guatemala — as it already has for a number of years — it may soon be coming to a country near you.

This article first appeared in the PanAm Post.

Armando de la Torre contributed to this article.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.