Chronicles Editor Paul Gottfried was asked in October 2022 which topic offered the most potential for libertarian and paleoconservative collaboration. Speaking for the latter movement at a Mises Institute event, he said there was, with few exceptions, potential across the board.

This is because those who value liberty (libertarians) and those who value civilization (conservatives) have a common enemy: the left. Specifically, the common enemy is egalitarianism. This ideological quest for equality of outcomes unites those under the leftist umbrella, be they self-described progressives, Marxists, communists, socialists, or (left-)liberals.

Given its opposition to disparate outcomes and hierarchy, leftism is a plague that manifests in a sprawling, vicious leviathan that suffocates individual liberty and the natural family unit—as explained in Against the Left (2019) by Llewellyn Rockwell. Leftism also conflicts with religion because it is an alternative authority and source of morality that competes with the leviathan.

Although ubiquitous and tempting to wannabe rulers and those with a chip on their shoulder, leftism can never achieve its stated goal. Humans are not equal in their abilities and never will be. The social engineering for imposed equality, no matter how all-encompassing, is always in a battle with human nature and must indoctrinate each new generation away from their proclivities.

Where the Scars Run Deep

The truth about leftism’s destruction and false promises is abundantly clear in Latin America. One need look no further than Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela—all places of misery and, ironically, immense inequality. While preaching equality and a new socialist man, the ruling class have shown how redistribution empowers the state. They live in opulence and prey on useful idiots and nonconsenting souls alike—those who fail to escape.

The left’s notable legacy from these nations is lost generations of exiles who are living testament to the utopia that never was. As José Azel of Cuba has written, the decades-long migration of Cubans to the United States—centered on Miami, Florida—means “the authentic Cuba is the one Cubans have built in South Florida” and not in Havana, which is a shadow of its former self.

Yet we have seen in recent presidential elections the left’s march across Latin America, be that in Chile, Colombia, Peru, or Honduras. On October 30, 2022, Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva just prevailed over Jair Bolsonaro in the runoff vote, so Brazil has also joined the Pink Tide 2.0.

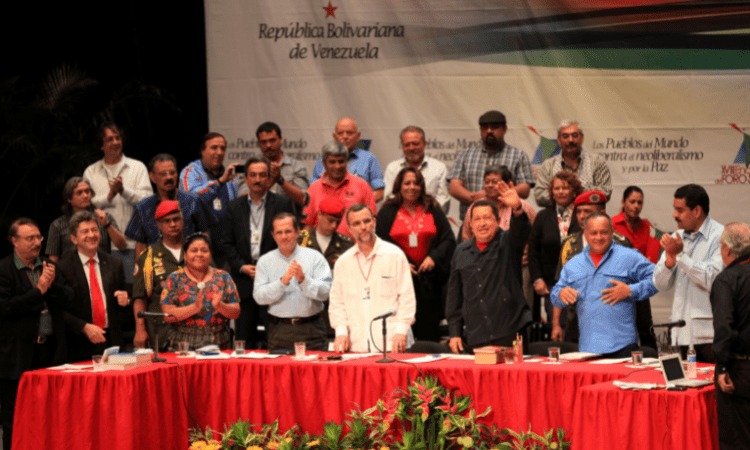

No matter how much pain 21st-century socialism inflicts, many people, like lemmings walking off a cliff, appear immune to seeing the connection. The Bolivarian Alliance and São Paulo Forum (now known as Grupo de Puebla) of the late Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro are reinventing themselves and permanently reshaping nations for the worse.

Insofar as there is a right wing in contemporary Latin America, it has its own interventionist tendencies, lacks ideological unity, and does not represent classical liberalism. However, at least it does not preach egalitarianism.

Latin America’s historic right-wing authoritarianism, such as Augusto Pinochet’s regime in Chile, has been reactionary and temporary, with the late general handing over power after the 1988 referendum for democracy. As Spanish economist Daniel Lacalle has explained, “right-wing interventionism is damaging … and must be condemned. However, it is not perennial.”

Unfortunately, “once the left take over institutions,” Lacalle continues, the big problem is that they “start to impose socialism as radically as we have seen in some Latin American economies … [and] you do not get rid of them.”

The Egalitarian Siren Song

Leftist rhetoric, which ignores or denies natural differences between populations, appears to be especially attractive, and dangerous, in Latin America.

First, Latin America’s poverty relative to Anglo-America invites scapegoating. The imperialista wealth to the north must have come at Latin America’s expense, so the logic goes. This line of thinking was expounded by the late Eduardo Galeano’s 1971 work: The Open Veins of Latin America, which remains influential. He pointed the finger at colonial powers while contemporary leftists point their fingers at boogeymen such as the International Monetary Fund and the so-called vulture funds that risk lending money to Latin American governments.

Second, such is Latin America’s ethnic diversity, income and wealth inequality are inevitable. While some people wish to live in ways that keep them in subsistence-level poverty, others have the talent and inclination to live with First World amenities. The latter typically segregate themselves away in gated communities, which make the contrast of living standards even starker. Envy from those on the outside is easy for populists to tap into for class warfare.

Finally, Latin America does not have the Anglosphere’s history with centuries of at least some sovereignty for the subjects of the monarch. As explained by Carlos Rangel in The Latin Americans (1976), those who have never known sovereignty or equality before the law—rather than equality of outcomes—are inclined to seek a more benevolent ruler rather than to rule themselves. This penchant for a savior ruler infers doing something is better than doing nothing, and it negates letting gradual, organic growth pay dividends, as it did in the Anglosphere.

To be fair, some indigenous groups have resisted leftists when they want to upend the indigenous way of life. The Miskitos of Nicaragua, for example, found themselves refugees in Honduras after the Sandinistas had no interest in local autonomy. Likewise, Ixils in Guatemala got caught up in Castro’s quest for an international Marxist revolution. Many Ixils unfortunately perished in the crossfire, and the Guatemalan government armed Ixils and other campesinos in Civil Defense Patrols to resist the leftist guerrillas.

An Unaffordable, Luxury Program

As I write this from Buenos Aires, Argentina—inspired by Rockwell’s book—I think of how the world has passed this nation by. While Argentina has spent the better part of a century squabbling over a smaller pie, defaulting on her debts, printing money, and unionizing her economy, much of the rest of the world has grown and left Argentina in their wake.

Argentina’s leftists, who follow the legacy of Juan Domingo Perón (1895–1974), have failed to grasp that you cannot make a poor man rich by making a rich man poor. The Peronistas are obsessed with (1) redistribution and (2) scapegoating. The first destroys incentives and productivity; the second deflects responsibility and breeds dependence on foreign aid, including from the vilified sources. Perón and his adherents have favored the short-term bread and circus over long-term development, and the results are sadly visible throughout an Argentina in decline.

Leftism is an expensive endeavor. Its cost is particularly painful for the poor who cannot afford it: Latin Americans. If your economies are almost 90 percent less productive than those of Anglo-America, fixing that problem—with free enterprise and investment—should be front and center. The welfare state and foreign aid are no substitute for the private sector and never will be.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.