More than a decade’s work has gone into a game-changing idea for Honduras, but that idea is on the ropes, as are its benefits. New President Xiomara Castro is undermining the zones for employment and economic development (ZEDEs) in their infancy, and there is no longer a legislative or constitutional basis for more to exist.

Castro’s actions reflect a choice to reject economic opportunity if it threatens centralized control. The ZEDEs are a badly needed innovation and disruption within a largely failed state. To Castro and her socialist kin, such an escape cannot stand, and her government has refused to negotiate.

Not only do ZEDEs go against centralization, they demonstrate tangibly that individuals can do better without interventionist rulers. The ZEDEs are flipping anticapitalist rhetoric on its head, bringing swift foreign investment, and humiliating the progressives who demonize the big-bad United States to the north—but the ZEDEs are on hold and unlikely to expand.

The Opportunity That Captivated Me

As one of the original true believers, I have followed the ZEDEs from the beginning. In 2010, as a journalist in New Orleans, I became acquainted with the Honduran diaspora, which was prominent at Louisiana’s Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. Mayra Pineda, a former Honduran diplomat, still leads the organization and was helpful with my work.

She and her colleagues hosted an event in September 2010—Enfoque Honduras—to publicize trade opportunities with the Central American neighbor. There was optimism in the air, and stability was returning after the 2009 removal of Manuel Zelaya from the presidency.

My curiosity was piqued, and I soon learned of the ZEDEs plan for Honduras, then known as charter cities. My youthful anarcho-capitalist sentiments were at their zenith, and the idea of startup jurisdictions led by entrepreneurs was a dream.

Others felt the same way and even moved to Honduras to join what they saw as history in the making. In 2011 and 2012 there was a flurry of blogger and media interest, and hopes were high that successful ZEDEs could catalyze reform and be replicated elsewhere. Even the Economist magazine reported on the “special development regions”—albeit in an unfavorable manner.

In 2013 I attended a conference in Guatemala City on startup cities, hosted by Zachery Caceres, and got to know the personalities eager for jurisdictional innovation. Educational entrepreneur Michael Strong was one of the notable leaders, as was law professor Tom Bell of Chapman University.

Strong later wrote an article for me that I published: “How ZEDEs Can Make Honduras Prosperous.” He emphasized the need for “zones that provide access to higher quality law and adjudication,” not just low taxes and light regulation. Honduras needed First World rule of law, which the ZEDEs offered.

The Tough Reality on the Ground

Eager to go beyond articles and podcasts, I planned a trip to Honduras to see for myself what was happening. A think-tank friend had returned home to San Pedro Sula after studies in North Carolina, where I worked in 2011–2013, and he helped plan a week-long visit. A columnist in Tegucigalpa, the capital, was another friendly face who introduced me to local business leaders.

When I arrived in San Pedro Sula in late 2013 there was a city-wide blackout. However, the locals in Honduras’s second largest city were accustomed to living without electricity. My friend and I were still able to stop in at a restaurant, and I got to try huevos de toro (bull testicles). The restaurant had a plan B: candles and a wood-fired stove that cooked our meal.

The lack of electricity was my first experience with Honduras’s infrastructure. The roads were next to open my eyes. A British expat there with his wife and daughter joked that drunk drivers drove straighter than sober drivers. The drunks did not bother to dodge the endless potholes.

When I ventured out for the bus to Tegucigalpa, I sensed eyes upon me as a gringo out of place, and I did not feel safe. San Pedro Sula was known as the murder capital of the world, exacerbated by drug-cartel battles for the transit point. A reporter and translator from Arizona who lived in San Pedro Sula shared with me how he had witnessed gunfights firsthand, and he had horror stories that do not bear repeating.

Although I enjoyed my stay and met worldly people, my observations generated two paradoxical conclusions: (1) Honduras badly needed the ZEDEs, but (2) the disorder and crime made me doubt that meaningful ZEDEs would ever happen. Consider that Honduras ranks 157th out of 180 countries in the Corruption Perceptions Index.

The notion that there would be a sustainable libertarian oasis in Honduras was quashed in my mind. The best one could hope for was a marginal respite for a lucky few from the clutches of predatory officials. Worse, those officials could perhaps abuse ZEDEs as vehicles for political patronage, although the intense scrutiny made that unlikely.

Further, I sensed there was insufficient support for the ZEDEs—even though Hondurans were eager for foreign employers and believed they treated and paid workers better. Socialists had dishonestly but successfully painted the ZEDEs as an imperialist, antidemocratic plan to steal Honduras.

That silliness ignored sober analysis and devoted efforts to make the projects conform with Honduran constitutionality and tailored for Honduran benefit. As explained by Ryan Berg of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “ZEDEs are circumscribed by Honduran law … in all topics related to sovereignty.” That includes the “application of justice, national defense, foreign relations, electoral matters, and issuance of identification documents and passports. Furthermore, any legal framework adopted by ZEDEs must provide equal or greater protection for human rights than what is contained within the Honduran constitution.”

The End of a Long Road

There have been many dramas between then and now, including a 2015 public-relations dustup in San Francisco. Then President Juan Orlando Hernández was to participate in a “Disrupting Democracy” speaker series, but the meaning was lost in translation. When Hérnandez backed out, the embarrassing ordeal was fodder for the communists at TeleSur and Mother Jones.

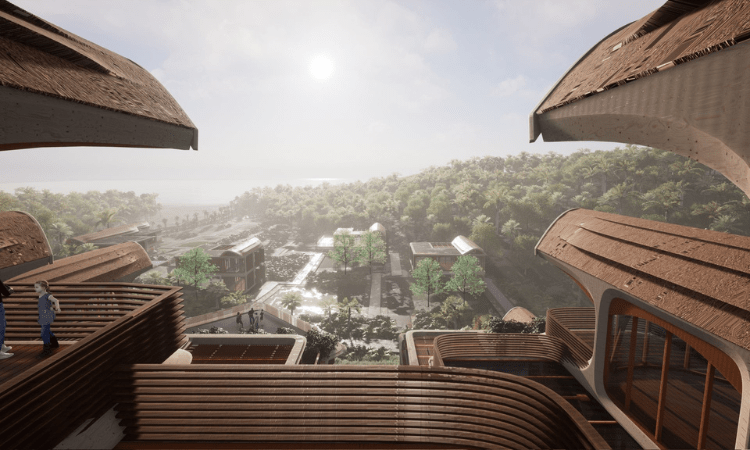

My colleague Paz Gómez and I have covered the ZEDEs in detail, perhaps more than any other topic. In 2020, we sensed that the ZEDEs were taking off again with the Próspera project, primarily on Roatán Island. Próspera has raised $80 million in capital, capped long-term taxation at no more than 7.5 percent of GDP, and de facto declared bitcoin legal tender. Berg has noted other ZEDE success stories in manufacturing and agriculture, providing economic benefits in short order.

In April 2022, however, the Honduran National Congress eliminated both the law and the constitutional amendment that enabled ZEDEs. Now the president is tightening the strings to make the handful approved earlier struggle to survive and plan for the future. Gómez provided this explanation in the Impunity Observer:

The ZEDEs’ purpose was to boost economic development with streamlined processes, investor-friendly regulations, and alternative decision-making models, including independent arbitration. However, allowing for a different set of rules raised concerns regarding Honduran sovereignty and human rights.…

On April 19, 2022, Congressional President Luis Redondo submitted a motion to dismiss ZEDEs.… he needed the approval of at least 86 legislators out of 128. All congressmen favored it.…

The legislators explained that ZEDEs “contravene the nation-state logic, the rule of law, justice, democracy, the government system, the territorial balance of power, and in general, Hondurans’ dignity and human rights.”

To their credit, many of the ZEDEs proponents hung in there through various iterations and persisted for a decade. Still, some are clinging to hope that international law and trade agreements will permit established ZEDEs to continue. Whether they have any future remains to be seen, but the likelihood of attracting major capital is slim.

The fog of political rhetoric has impeded some of the world’s best legal scholars and economists from helping Honduras bring in the necessary capital and know-how to generate substantive development. An opportunity has been lost, and the losers are the Honduran people, now more than ever under the thumb of the ruling party.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.