I recently returned to Guatemala.

A group of legislators are in an unexplained and sudden hurry to debate a few hasty and contorted reforms to the Guatemalan Constitution. This should surprise any neutral observer of public affairs.

The content of the reforms the CICIG is proposing is extremely debatable, and its long-run effects — which I will address in subsequent articles — might be very harmful. Hence, this deserves a lengthy and very detailed parliamentary debate.

One should not forget there is a constitutional precept that requires every public officer to make an oath of fidelity to the Constitution of the Republic. In this vein, Article 154 states: “The public function cannot be delegated, except in the cases noted by law, and it cannot be exercised without a previous oath to uphold the Constitution.”

What is even more questionable about the initiative is that these reforms emerge from an entity with no legal faculty to do so. The initial purpose of the CICIG, as written on its website, is completely different:

The CICIG’s mandate is unprecedented among UN or other international efforts to promote accountability and strengthen the rule of law. It has many of the attributes of an international prosecutor, but it operates under Guatemalan law, in the Guatemalan courts, and it follows Guatemalan criminal procedure. CICIG carries out independent investigations into the activities of illegal security groups and clandestine security structures, which are defined as groups that: commit illegal acts that affect the Guatemalan people’s enjoyment and exercise of their fundamental human rights, and have direct or indirect links to state agents or the ability to block judicial actions related to their illegal activities. The influence of these groups within the State is considered to be one of the cornerstones of impunity in the country and a major obstacle that impedes efforts to strengthen the rule of law.

What does all this have to do with your effort to promote constitutional amendments for the judicial sector, Mr. Iván? Why, in contrast, have you not pioneered something related with your original assignment, to tackle the inhumane despotism of the CUC in the rural areas?

By the way, Iván: why is it that Senator Álvaro Uribe, former president of your native Colombia, described you as a “nefarious” assistant judge of the Supreme Court of Justice? What reasons did he have?

My intent is not to delegitimize your work with this, but I do think that any information about you is relevant to the interests of the Guatemalan public, especially if it comes from a person as qualified as the former president of your native country.

But let us return to the topic that concerns us all. Article 137 of the Guatemalan Constitution flatly establishes: “The right of petition in political matters belongs exclusively to Guatemalans.”

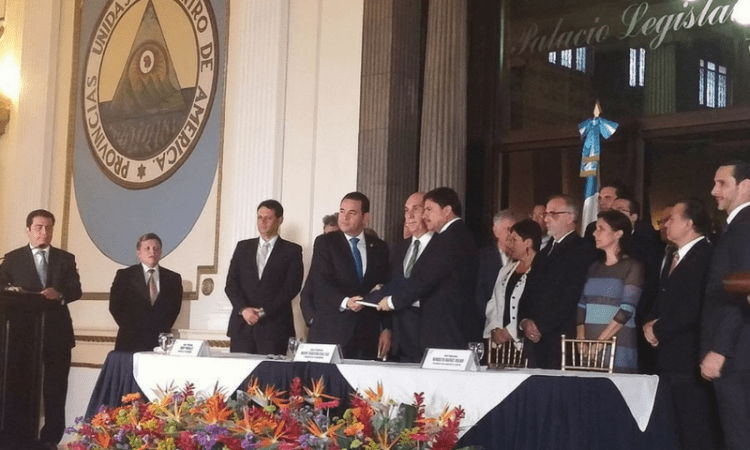

Hence, how do you explain the scene — depressing, in my opinion — of your active presence at the Congress, while your compliant “subordinate,” the Attorney General Telma Aldana, encouraged you from the gallery with a smile?

To cap it all off, everyone here is inferring that Todd Robinson, the malignant US ambassador in Guatemala, is behind this unexpected appearance of yours. Although he is still in office, I believe, and so does he, that he will not remain there for long.

Would this last assumption be the real reason for such a hurry in Congress?

Robinson, just like his predecessor Arnold Chacón, arrived in Guatemala after obvious training from the US secretary of state on how to promote “regime change” in this country.

Both these men lack the right to promote an initiative of constitutional reforms. Article 277 of the constitution grants this privilege only to the president of the republic in the Council of Ministers; to 10 or more legislators; to the Court of Constitutionality; and to the people, endorsed by at least 5,000 citizens duly registered in the Registry of Citizens.

In Guatemala, however, they can illegitimately assume the faculty to intervene and strike at the very roots of this nation, without concern for a potential nationalist uprising against them. Can anyone imagine what would happen in Mexico if foreign bureaucrats tried to do what they do here in broad daylight?

From my perspective, this humiliating prostration of Guatemala’s national pride began with the Contadora Process during the government of President Vinicio Cerezo, and became definitive with the peace agreements signed under the government of Álvaro Arzú. Since then, Guatemala stopped being the sovereign nation that its national anthem describes with pride.

Nonetheless, the government of Alfonso Portillo inflicted the final stab to Guatemala’s sovereignty: bringing the CICIG to the country. A great number of unwary Guatemalans praised this initiative of Edgar Gutiérrez, then minister of foreign affairs.

The CICIG, managed by UN Commissioner Iván Velásquez, has made credit-worthy achievements, in contrast to its two predecessors: the Spanish chaotic Castresana and the corrupt Costa Rican Dall’Anese. This, however, has cost a significant part of Guatemala’s national independence, something that becomes increasingly harder to recover as time goes by.

Furthermore, and sadly, it appears they attained the unconditional vote of more than 20 renegade parliamentarians, probably blackmailing them with retaining their useful North American visas, or offering them protection in case of accusatory proceedings held by the CICIG. Moreover, a few legislators might have ideological affinity with those who disrespect the democratic sovereignty of the Guatemalan people.

This wretched process has proceeded on account of the shameful lack of sovereign power that is evident in Guatemala’s current reality, especially since the well-deserved coup against Otto Pérez Molina happened.

Certain subversive and violent groups of the extreme left, which discreetly act in the shadows of public authorities, celebrate this kind of “reality show.” Just to name a few: the Mirna Mack Foundation, CALDH, the Guillermo Toriello Foundation, the CUC, FRENA, and the International Commission of Jurists (Ramón Cadena).

Certain public officers, comfortably safe in their seats, sympathize with it as well: human-rights prosecutor Jorge de León Duque; former President of the Constitutional Court Gloria Porras; and permanent opportunist Frank La Rue.

There are a few more. I would say there are about 1 million emotionally compromised advocates in this country that promote the destruction of the entire legal system that Guatemala has had over the last two centuries.

Let me finish with another brief comment about the content of that unconstitutional proposal that ironically intends to reform the judicial sector.

There is no doubt that the intention is to subjugate the Supreme Court, the Appeal Courts, and eventually the Constitutional Court, in order to create a National Council of Justice. This entity would become the all-embracing dictator when choosing the magistrate candidates.

This would culminate the siege on the dying sovereign powers of the State of Guatemala.

(To be continued.)

This article first appeared in El Periodico.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.