In their first weeks of power, Cuba’s new rulers pushed out measures that bought them immense popularity. Urban rents were cut in half; land values lowered; vacant lots placed on sale for low-cost housing projects; utility and telephone rates slashed. To peasants in Pinar del Río, Cuba’s westernmost province, Fidel himself was signing over parcels of state-owned land.

Those measures piqued the Americans who disliked anything that smacked of socialization. Especially offended were the yanquis who owned Cuba’s telephone and utility companies, and quite a number more who owned agricultural enterprises or landed estates.

The new regime’s policies also targeted Cuba’s moneyed classes who had been able to save on taxes by bribing Batista’s officials. Last but not least, the esbirros – people who had worked for Batista in any capacity – faced a triple threat. Those who were arrested got jail if they were lucky and the firing wall if they were not. All properties belonging to esbirros, without exception, were seized.

To the ordinary rich Cubans who owed back taxes, revenue agents offered favorable repayment terms. Most people found repayment a better option than others on offer. With back-tax payments flooding into government offices, plus proceeds from confiscated properties, Fidel’s regime acquired a fortune and became the best-endowed revolution of modern times.

La chusma, the untamed mass, identified ever more strongly with the revolutionary regime. How come? Emi and his pals looked sideways at those who had done nothing against Batista’s regime while saying they hated it.

To those who actually did fight against Batista, the emotional outpouring of the masses for Fidel was a blatant hypocrisy. The so-called revolutionary crowd was trying to erase its earlier inaction by giving Fidel those wild displays of support. And Fidel was happy to accept the acclaim.

Even the old fighters, with all their seriousness, did not miss out on the fun of those early days. Emi was an attorney with revolutionary credentials and good contacts in the new regime. The country’s laws were in a state of total flux, while people’s pockets were bulging with money from all the economic breaks the regime had given. As a lawyer Emi had never been busier, nor had he prospered more.

The honeymoon was short. Barely two months into the takeover, a group of 40-odd fighter pilots from Batista’s air force went on trial for war crimes. Accused of bombing rebel positions during the recent conflict, the airmen defended themselves by saying they had actually dropped their bombs on empty areas and made false reports to their superiors. Their stories were verified, and in a surprise verdict the judge found the airmen not guilty.

Revolutionary regimes, however, tend to reject surprises which are not of their own making. That verdict enraged the revolutionary mob. A riot broke out in Santiago de Cuba, where the court had met. Across the island in Havana, Fidel went on TV and demanded a new trial. The trial judge was replaced by a comandante, “Redbeard,” who was one of Raúl’s loyal men.

Redbeard convened a second trial. On the same evidence, he convicted all the airmen and gave them prison terms of up to 30 years. Fidel pronounced a new legal standard: “Revolutionary justice is based not on legal precepts but on moral conviction . . . Since the airmen belonged to the air force of [Batista] they are criminals and must be punished.”

* * *

That statement contained a strong clue about the nature of Fidel’s regime. In their talk after Batista’s overthrow, el viejo the savvy older man had gotten it wrong while Adolfo the greenhorn youngster had called it perfectly right.

One of the regime’s first edicts was to cancel the system of botellas or sinecures on which Riverito and other journalists depended for their livelihoods. At the same time, negative statements began appearing about journals that had prospered during Batista’s rule. People who wrote for those journals – the gamut of Cuba’s free press – were being called “traitors,” “pharisees,” “sellouts” or “botelleros,” which had suddenly acquired a sinister new meaning.

The inference was false. Cuban newspapers heavily depended on sinecures to help them balance their accounts. Salaries were kept low in expectation that reporters – like workers in the service trades – would make much of their living in extras. The botellas had no relation to what anyone wrote; only to his or her standing in the profession. They were not bribes, any more than tips to your favorite waiter or concierge would be.

Of course the new rulers knew it perfectly well. They simply wouldn’t miss a chance to help themselves and their friends at the expense of wealthy people from the old regime. That they did, adding insult to injury, with the holier-than-thou attitude which revolutionaries have eternally deployed against an old regime’s corruption. Old-style enrichments are painted as morally bankrupt, while the new regime’s money-grabs are extolled as a vital means to distribute well-being or deliver “social justice.”

In short order the new rulers had Cubans accepting that the Havana newspapers of the old regime had sold their souls for sinecures. After canceling the sinecures, the new regime seized the presses, offices and physical plants of all newspapers that had given support to Batista. In that removal of property, officials made no exception for journals which had shown balance by also giving generous coverage to the rebels.

The real objective was twofold: to abolish those newspapers which the regime did not fully trust; and to enrich others – like the July 26th newspaper Revolución and the Communist newspaper Hoy – on which the regime felt it could count 100 percent.

It was indeed a dramatic and visionary solution to the problem of an unrestrained press. Cuban media had been free and feisty to the point of rambunctiousness. Batista had suspended press freedoms from time to time and been battered for it. But Batista never imagined the ‘final solution’ which the new rulers now took care to apply by stages. In the end Fidel’s regime did not precisely banish corruption. It made corruption invisible, and therefore total, by canceling journalism itself.

It was indeed a dramatic and visionary solution to the problem of an unrestrained press. Cuban media had been free and feisty to the point of rambunctiousness. Batista had suspended press freedoms from time to time and been battered for it. But Batista never imagined the ‘final solution’ which the new rulers now took care to apply by stages. In the end Fidel’s regime did not precisely banish corruption. It made corruption invisible, and therefore total, by canceling journalism itself.

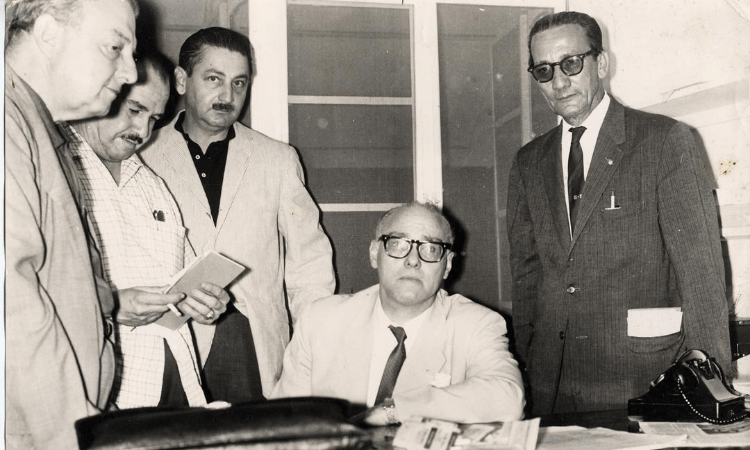

Against this juggernaut, even Riverito – a man who had defended his family through the worst of times – was no match.

In an abrupt role-change the younger son intervened on his father’s behalf. With the revolution’s coming to power the 23-year-old had gained a senior position in the Communist Party; no less a personage than Raúl Castro had appointed him to the leadership of the Party’s youth organizations in the Havana district.

In Adolfo’s eyes – he had put away his underground name – el viejo was a political innocent. He might not understand the revolution, he might not go for communism, but those were no reasons to treat him harshly. Adolfo wrote a brief in which he decorously testified that Riverito had given refuge to communist militants being hunted by Batista’s police; in other words, to several of Félix’s buddies who had stayed as guests in his father’s house while they were on the lam.

Here was the rub: Adolfo could only give his memo to communist leaders who were still sitting in the peanut gallery. The July 26th people were the ones in power. They had no reason to help an older journalist with close ties to the ancien régime.

To Adolfo’s parents, only one thing was certain: this was not their Cuba any more.

The complete book is being published by Pureplay Press. The book, including all material therein, is copyright © 2020 by David Landau.

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from now through early October, the Impunity Observer will publish excerpts from Landau’s book

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.