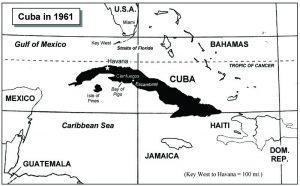

Monday, April 17, 1961. Invasion! The enemy had landed a force at the Bay of Pigs on Playa Girón and Playa Larga, south central shore of the island.

Adolfo demanded a safe-conduct to the front as Mella’s combat correspondent. By afternoon he had left for Santa Clara with his chauffeur Bebo, the two of them armed with checas and ready for action.

Tuesday, April 18. The town of Santa Clara, 100 miles from the invasion, was a bedlam of uniforms and trucks. Members of the Rebel Youth were taking part in the recogida or mass arrest. The general order was simple: imprison anyone suspected of counterrevolutionary sympathies.

People enthusiastically enforced the measure. Suspects were taken house by house, street by street, neighborhood by neighborhood. Tens of thousands of people in the city had already been jailed with no pretense of procedure. As the city’s prisons couldn’t hold them, they were being kept in improvised concentration camps.

The man running the recogida in Las Villas province was Arnaldo Milián, a veteran Communist/PSP leader who specialized in agriculture. Speaking to Adolfo, he explained that the next enemy attack might be a simultaneous assault in several areas; therefore it was necessary to have reserves ready for action and to be vigilant against sabotage or efforts to block reinforcements.

Arnaldo’s presentation was calm, precise, detailed and professional. Adolfo felt reassured to see the old Party coming to the fore in a moment of crisis. “The cold blood and discipline of the communists is vital to the survival of the revolution,” he wrote.

San Blás. In swampy terrain close to the action, a small militia contingent was forming ranks when Adolfo and Bebo arrived. A thin young man approached with a smile. Adolfo recognized “Pijirigua,” a peasant lad he had met and befriended years before at meetings of the Socialist Youth.

Adolfo’s eye fell next on Major Félix Duque, a short man in a green beret who was white with road dust. The major was talking with militia officers. As Adolfo approached, Duque turned to him without ceremony and boasted: “These militia people are superb! I have never fought with better troops.”

“A large number of guns are coming up toward the swamps,” Adolfo said.

“I’m waiting for them,” Duque answered. “When they get here, we are going to turn them into dust.”

Several militia soldiers nearby were trying to work a mortar. Duque went over and dropped in the first round. A sharp, dry detonation rang out, and they were in the war.

Pijirigua went to the head of the column with Duque while Adolfo fell in with the body of troops. They advanced in two columns, one on either side of the road so they could take cover quickly. The enemy was dead ahead.

A few minutes along the road they came upon a corpse in the camouflage uniform of the invaders – the body so covered with white dust that its features were barely visible. The militiamen passed by without a stop, their boots making a dull tramp on the interminable road.

“We must retreat!” a militia officer exclaimed. “This area is controlled by mercenaries.” Castro’s soldiers used that word on faith – believing that no Cuban would take up arms against the revolution unless paid by Americans.

As Adolfo was thinking how sensible retreat might be, Pijirigua ran up and said excitedly: “We’re advancing!”

Wednesday, April 19. “The enemy troops are now against the beach. They have broken ranks. Let’s go!” Pijirigua called out.

Adolfo and Bebo went with Pijirigua to witness the end of the battle. Near San Blás they found a company of militia spread out over a field, scavenging. Among the bushes, enemy soldiers had strewn empty cans and dark tablets that looked like soap.

“Those are K-rations,” Pijirigua said proudly. “I learned that during training.”

A little farther along they found a Browning pistol which Adolfo’s friend was happy to claim. Rebel Army troops were tearing a silk parachute into strips for souvenirs. Adolfo would have loved to have one, but he refrained because he was not a combatant.

Near Playa Girón, two men in camouflage uniforms came walking out of the field with their hands raised. Adolfo stared at them in cold hatred. Those men were the Enemy. They had come to shed the blood of his comrades and restore Cuba as a yanqui colony.

Even though the soldiers had surrendered themselves, Adolfo thought about shooting them.

One of the prisoners, a sturdy fellow with a short haircut, said: “They left us in the lurch. This has been hell.”

The comment about the Americans rolled off the prisoner’s tongue in Cuban vernacular. Adolfo was ready to blow his top. A CIA mercenary had no right to sound like a Cuban.

The prisoner and his companion, a very tall thin man, were dehydrated, their lips severely cracked. Pijirigua tossed his water bottle to them. They drank desperately.

“Thanks,” the taller one said. “It’s a strong sun here. I’m from La Víbora. Where’re you from?”

La Víbora was a lower-middle-class neighborhood in Havana. Adolfo was not about to say he was from El Vedado, a neighborhood quite a bit fancier than that of his captive.

“Get into the jeep,” Adolfo answered with scorn, pointing with his checa. “You are my prisoners, not my guests.”

Saturday, April 22. A group of youth directors including Adolfo went to meet with President Dorticós and other leaders at the Presidential Palace. As usual Fidel was there, thinking aloud in a stentorian voice. He spent many words praising the air force for sinking the enemy’s supplies at sea. From out of nowhere he brought up Major Félix Duque, whom Adolfo had mentioned in his account for Mella.

“He is always thinking about how to make himself conspicuous, how to call attention to himself,” Fidel said. “Duque is one of those men who do not accept the lowly place in history to which their own mediocrity condemns them.”

Adolfo found the statement terribly rough. On the beaches Duque had been a gallant, heroic defender of the revolution. If Fidel so resented that man whom he knew as a faithful subordinate, how must he feel about the simple soldiers, workers and peasants under his command?

But no, Fidel had a point. It was harsh but true. Duque was a soldier, a fine soldier, maybe even an exceptional soldier – but in the end he was dispensable as every soldier must be. Fidel was Fidel, indispensable. Adolfo and his comrades were so many men among many. Fidel was unique, everyone in one.

The complete book is being published by Pureplay Press. The book, including all material therein, is copyright © 2020 by David Landau.

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from now through early October, the Impunity Observer will publish excerpts from Landau’s book

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.