{from Emi’s recollections}

Sunday, April 23, 1961. I decided to spend the afternoon at the El Vedado apartment of Adela, a widow in her late thirties who lived with her white-haired mother. When I dropped by, they were having a late lunch and invited me to join them.

Like most Cubans they had been following the dramatic events of those days on radio and television. They did not know the extent of my involvement in clandestine activities, but they understood I had a lot on my mind; so after a long and pleasant conversation they suggested I use their back bedroom to read and nap.

I accepted their kind offer and retired to the bedroom. Out of concern that my hostesses might be alarmed at the sight of a gun, I put my pistol on a shelf behind a row of books.

Immersed in reading, I noticed raised voices from the living room. It sounded like an argument. I walked down the hall to the living room and asked, “What’s wrong, Adela?”

In a dismayed voice Adela said, “It’s the police.” At that instant I became aware of a man pointing a submachine gun at me.

Actually it was not the police but State Security; three agents commanded by a lieutenant in his early twenties. With them was a fifth man, a prisoner who had guided them to the apartment – a snitch.

In putting my pistol aside as a concession to the feelings of my hostesses, I had ignored another cardinal rule. Had I ruined my chances for escape? Or unwittingly saved my own life by ruling out a firefight?

My captors heard from me a carefully prepared story which had some grains of truth. I was a freelance journalist for CBS television news and for The New York Times. I expected to sell my reports on Cuba for substantial sums.

“And did you need this for your reporting?” the lieutenant asked, pointing to my pistol which they had found in a quick search of the house.

I replied: “We have all seen the climate of unrest, confusion and violence in the country. I have simply carried that pistol for my own protection.”

The lieutenant obviously didn’t believe my story, but at least it had given me something to say that did not antagonize him or compromise the two women.

The Security men kept us all in the apartment for some hours. Either they hoped to entrap someone else or they preferred not to show an arrest in daylight.

One of the many things that went through my mind in those hours was the conversation in which I had told J.B. that I would have 45 days in Havana, 50 tops, before getting arrested. This was the 51st day of my return to Cuba.

My paramount concern was to help the two women who had been so kind to me. As it turned out, the mother had similar feelings toward me. When one of the agents threatened her, she said: “I am an old woman. I have lived enough. I don’t care about myself. But I do care for the lot of this man who is in the bloom of his life.”

Perhaps my story distracted the agents, because although they searched the house they forgot an elementary police measure: they didn’t search me. That was fortunate because my shirt pocket contained three very thin strips of paper on which I had written messages to give my radio operator for relay to the United States. When after dusk I was walked to the Security car half a block away, I managed to pull out the papers, wad them into a ball and toss them into the grass along the sidewalk.

At State Security headquarters I was ordered to sit on a bench in a hallway. While there I witnessed the frequent coming and going of numerous homosexuals who were identifiable from their voices and their exaggerated gait. They were dressed in everyday casual clothes but obviously worked for the G-2. Most of them looked excited, visibly rejoicing in their work as informers, surely because it enabled them to strike back at a society that had scorned them.

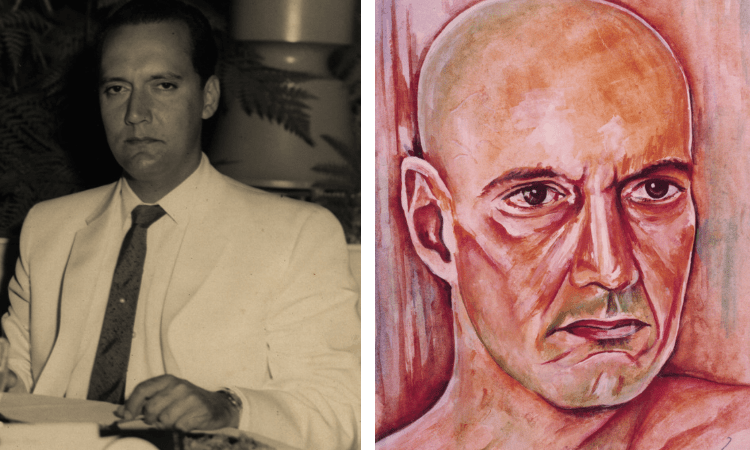

I sat on the bench for two hours with no one questioning or even approaching me. Around 11:30 p.m. someone came to fetch me and guided me to a small office, where a desk and four chairs occupied almost the entire space. Waiting there for me was the boss of Castro’s counterintelligence whom everyone, for the obvious reason, called Redbeard. With him was the arresting officer, identified as Lieutenant Cuenca, plus a young captain whose name was not mentioned.

I was placed in a chair facing Redbeard. All lights were turned off except for a lamp on the desk which was directed upwards into my face from only four or five inches away. That seemed to me a ridiculous bit of Hollywood drama.

Redbeard began with general inquiries about my activities. I repeated that I was in Cuba as a freelance journalist.

“That looks like a front for the CIA,” he said.

To establish my revolutionary sentiments, I began what turned into a monologue on revolutions in general and the Cuban revolution in particular. I asserted that the struggle against Batista had been a political one and that Castro, in superimposing a different agenda on the revolution, was creating a schism that could have been avoided.

The masses, I asserted, had been fed a legend about the revolution that did not correspond to the facts. The revolutionaries against Batista – and I identified myself as one of the first – mostly supported the laws put into effect by Castro’s government. We were just not ready to accept a communist regime.

As I told my interrogators: “The communists didn’t join the fight against Batista until victory was in sight.” The American press, I added, found the subject very juicy; I intended to score a journalistic coup and make lots of money with my reports.

While talking I managed to inch the lamp away from me and direct it toward the wall without raising objections from my captors.

Having mentioned communism, I spoke about Russia – its history since the time of Yemelyan Ivanovich Pugachev’s revolt in the 18th century, the peasant uprisings of the 19th century, the Russo-Japanese war of 1905, Trotsky’s role in the 1905 revolution, the “Potemkin” incident where food protests led to an unexpected twist; then the massive events unleashed by World War I, the February 1917 toppling of the czar, Kerensky’s government, Lenin’s ride in an armored train across Germany, his arrival in Petersburg, his going underground; “Today is too soon, the day after tomorrow will be too late;” the “ten days that shook the world;” Lenin in power, agrarian reform, Lenin the realist advising acceptance of peace, the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the civil war, Trotsky and the Red Army, the shooting of Lenin, his convalescence, recovery, stroke and death, the testament, Stalin’s grasping for power, purges.

Throughout my monologue I felt somehow mortified by a deficiency in my critical analysis of communism. Though I had read much of Lenin’s writing, I had read little of Hegel, Marx, Engels and others whose works were essential to a good understanding of the subject. That deficiency seemed not to bother my captors, who listened attentively throughout. At least I had avoided a real interrogation and turned what could have been a very unpleasant evening into a passable one.

Redbeard concluded the interview by saying: “Doctor, we need people like you to give lectures to our men.” In the circumstance I took it as a compliment.

I was sent to a room that had been converted to a cell. It held twenty men. There I slept on the floor during my first night as a prisoner.

The complete book is being published by Pureplay Press. The book, including all material therein, is copyright © 2020 by David Landau.

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from now through early October, the Impunity Observer will publish excerpts from Landau’s book

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.