Brand’s chief partner in Havana was Efrén Rodríguez, the fellow attorney who had barged into his office two years earlier with exclamations about communists in the regime. Those comments had alarmed even Brand, who pressed extroversion to its limits.

Efrén, a master at demolitions, had been the author of numerous explosions in the capital that the regime could not conceal from an anxious public. Fidel’s agents had him at the top of their most-wanted list and were hard on his trail.

Brand had hardly caught up with Efrén when the other man said he had to leave.

“Where to?”

“A meeting of the section chiefs.”

“I don’t like that!” Brand exclaimed.

“Don’t worry,” Efrén said, flashing his good-natured smile and clasping a charm on his neck. “The Virgin will protect me.”

Next day Brand got word that Efrén’s driver had seen him leave the meeting in the custody of a plainclothesman who made it look as innocuous as possible. That was State Security, keeping a low profile. Efrén had managed to signal the driver by pinching his own throat in an unmistakable gesture: I’m taken, and I’m dead.

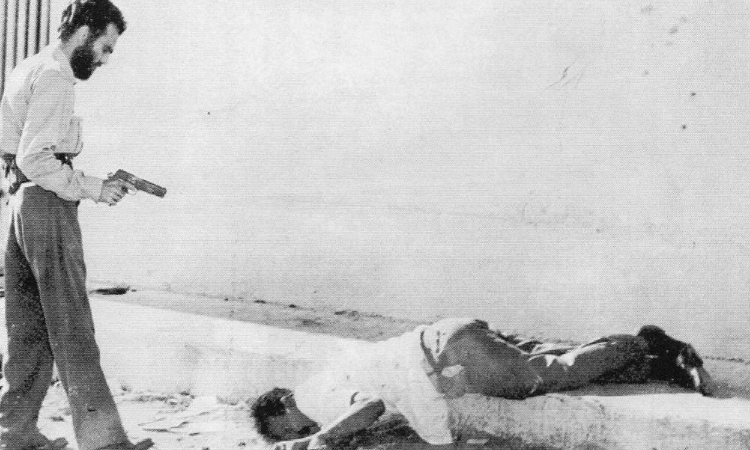

Within several days Efrén had been shot.

Brand’s Havana operation had lost its right arm. The others in Efrén’s network must now regroup. It was urgent for Brand to get weapons into the city. The people in Havana could set bombs and create disruptions, but without guns they could not make a decisive move.

Brand was also getting messages from Pinar del Río: When are the guns being dropped? Brand kept asking his CIA contacts in Havana and got no answer. As a temporary measure, he could supply the men in Pinar del Río with some of the guns from Ernesto’s farm.

Following Plinio’s death, Brand had no major contact in the Escambray; so the Americans gave him Ernesto, a businessman with strong credentials and a likable personality. Ernesto was not a patch on Plinio, but Brand always remembered a piece of advice he’d culled from Aristotle. In politics you do not create people; you work with the people you have.

After arranging for transport of the guns from the center of the island, Brand summoned Ernesto to a meeting and told him: “I’m ready to take the weapons from your farm.”

“We have a problem,” Ernesto replied. “The weapons are no good anymore.”

“No good! What do you mean?”

“A heavy rain swamped the ground where they were buried. The guns rusted, and they are now unusable.”

“All of them?”

“All.”

That could not be true. Before his drop, Brand had questioned the CIA people about how they were going to pack the guns. They had assured him the guns would be in top shape even if they had to sit for weeks in a swamp.

What was going on? It seemed Ernesto had panicked. Brand had seen it dozens of times. Well-to-do men like Ernesto just assumed they could be as effective in clandestine life as they had been in business. Then they came face to face with the pressures – horrible tensions of a kind they had never known, piling up with a speed they could not imagine.

With the state of terror that gripped the country, Ernesto had to be afraid of getting caught in a police trap. He didn’t want to risk having the guns moved off his farm.

What the hell, I’ll give the man a few days to get over his worries. When he’s cooled down he’ll let me have the guns.

Full orchestra

“Get up!” Brand’s friend Ana shook him in alarm. “Something is going on!”

“Tell me!” Brand was alert.

“The Ciudad Libertad is being strafed and bombed.” That was a local Havana airport serving domestic traffic as well as Cuba’s military.

“How do you know?”

“Someone called and said so. What can it mean?”

Six a.m. Saturday, April 15, 1961. Massive explosions rocked the center of Havana. It must be the CIA; no other explanation was possible. But Brand had gotten no word of an attack. Neither had anyone else in the underground, as far as he knew.

Without a doubt the goal of the attack was to destroy Castro’s air force in advance of a landing by troops. But why attack without sending word to the underground?

Brand knew that the Cuban force being trained in CIA camps was not nearly big enough to be preceded into battle with this massive overture. But for an American-sized intervention, the full-orchestra treatment would be just right.

Whatever their plan, the CIA was putting the underground into serious jeopardy. The bombardment would create massive confusion in the ranks. It was already sending Fidel a message he would not miss. “Make your arrests. We are coming.”

Coronation

Sunday, April 16, 1961. The day following the air attacks was given to a solemn ceremony for the seven Cubans who had lost their lives in the bombings. Fidel had called for everyone in the country to attend.

Heeding that call, people poured into Havana from all over the island. Adolfo, deciding to watch on TV, went to Joel Iglesias’s office where numerous comrades had gathered.

As soon as Fidel began speaking, the comrades tossed off comments while Adolfo paced the room. Fidel’s oratorical devices were familiar to all of them; their words raced ahead of his. Regarding the Americans, he exclaimed: “What they do not forgive us is that we have made . . .”

“. . . a revolution for the humble,” Adolfo mumbled.

Fidel had another idea. He raised his voice to thunder pitch, repeated the opening phrase and completed it: “What they do not forgive us is that we have made a socialist revolution under their noses!”

Adolfo turned to the screen, incredulous. At the huge rally, pandemonium had broken loose as thousands of arms, brandishing rifles, bolted upward.

The youth leaders jumped to their feet and embraced each other wildly. At last! Cuba had broken the bonds of yanqui domination. In that room, whether one was a socialist or a nationalist or simply a rebel with a cause, every heart and soul now beat as one.

Fidel closed his address with an order to mobilize. It was another piece of rhetoric. Every Cuban was already mobilized, waiting to join the fight.

After two years, through massive seizures of farms and industries, the nation’s economy was in the government’s hands; while political power, with hardly a meaningful objection, had been vested in a leadership body that a single man had designed.

Fidel had done the impossible. He had turned Cuba into a communist country. And here was the outcome – a coronation as glorious and momentous in its way as Napoleon’s.

To top it off, the moment had been crafted for such a declaration. Any fears or doubts about socialism were as nothing compared to the threat of invasion; and anyone in Cuba who took exception to socialism would be a coward or traitor bringing harm to the country in a time of war.

The complete book is being published by Pureplay Press. The book, including all material therein, is copyright © 2020 by David Landau.

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from now through early October, the Impunity Observer will publish excerpts from Landau’s book

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.