Prosecutor General Consuelo Porras’s tenure ends on May 14. The selection process for her successor began on January 18, when Congress convened the Postulation Commission (PC). This report seeks to explain the selection process and the attempts to influence who becomes the next prosecutor general.

The G13 is an informal but influential organization composed of the largest development-aid providers in Guatemala. The G13 has clout derived from aid budgets, and it has sought to supervise the appointment process. Further, as an active and prominent G13 member, the US State Department (DOS) has used the threat of sanctions to intimidate commissioners.

The prosecutor general holds a key center of authority in Guatemala, and many people have a keen interest in who occupies the position. Our investigation has uncovered an orchestrated team of social-media troll accounts devoted to this specific appointment. Who funds and directs the troll accounts remains uncertain.

Who Is the Prosecutor General?

The prosecutor general, at present a position held by Porras, is the head of the Public Ministry (MP). President Jimmy Morales appointed her in May 2018. She and her successors are responsible for managing criminal prosecution. Guatemalan courts can only process criminal complaints filed by the Public Ministry (MP).

The MP’s role is to protect the public by investigating crimes and processing them in court. The MP is an autonomous institution that receives constitutionally mandated government financing. The Guatemalan president appoints the prosecutor general from a list of six candidates given to him by the official PC.

The Guatemalan Constitution establishes who is on the PC. It consists of the presidents of the Supreme Court, Bar Association, and Bar Association Court of Honor. It also includes the deans of the country’s 12 law schools.

The Guatemalan Constitution states that the candidates must fulfill the following requirements to be eligible:

- born in Guatemala;

- over 40 years of age;

- an active lawyer in the Bar Association;

- recognized as honorable with no criminal record that denies civil rights;

- at least five years’ experience as a magistrate in the Appeals Court or similar courts or 10 years’ law experience;

- capable, honest, and fit for the job.

Any breach of these requirements results in a candidate’s disqualification.

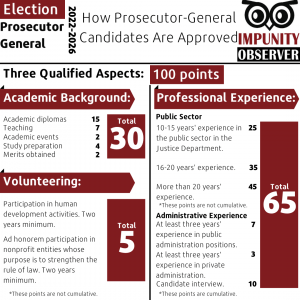

The Postulation Commission Law, which Congress approved in 2009, permits the PC to create additional criteria. The PC evaluates and updates the criteria every four years. The PC then scores candidates out of 100 points according to their professional experience, ethical record, education, and volunteer experience. The criteria and their weightings can change according to the commission’s judgment.

How the 2022 Process Has Unfolded

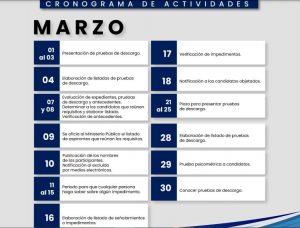

On February 10, the PC announced that interested lawyers had until February 21 to submit their applications, and 26 candidates did so. The commission checked the files to verify compliance with the previously stated requirements. Then 10 excluded candidates challenged their exclusion and requested reinstatement. They had until March 8 to do so with a revised application; one prevailed. On March 7, the PC listed 15 candidates who had fulfilled the requirements. This includes Porras, who is seeking a second term.

The PC and NGO Guatemala Visible have posted the official schedule for the subsequent nomination process. Third parties have been able to present objections on March 11–15 in a stage commonly known as the tacha, which refers to honorability. To eliminate a candidate in response to a complaint, the PC must obtain 10 votes from the 15 commissioners, a two-thirds majority. After the tacha, candidates have until March 25 to present any exonerating documents. On March 29, the PC will perform psychometric tests of candidate capability and behavior. On April 1–5, the PC will interview the candidates publicly.

The PC has established a threshold of 75 points for each candidate to make the shortlist that goes to the president on April 21. However, if fewer than six aspirants achieve this, the threshold decreases to 70 points, so all the candidates between 70 and 75 points would be added to the list. If the PC needs more candidates, the threshold decreases another five points until they include a sufficient number of applicants.

According to José Luis González, a litigator and former constitutional law professor, the PC Law and the new requirements are unconstitutional. His contention is that they distort constitutional provisions and add subjective evaluations of candidates’ merits. Further, the PC has demanded candidates provide a sworn statement that they have not represented people accused of narco-trafficking, organized crime, or similar crimes. Having done so is grounds for exclusion. This requirement is unconstitutional, González explains, because it violates the presumption of innocence and a lawyer’s oath to defend clients in need.

Interference in the Appointment

The G13 and the DOS are engaging themselves in local Guatemalan politics through sanctions, public announcements, and intimidation. Local organizations and the Guatemalan government are aware of and have publicly condemned this interference.

The Liga Pro Patria, a Guatemalan organization that advocates for the rule of law, has reported G13 interference, including from the DOS, in this electoral process. Further, the Liga claims the G13 supported a smear campaign against incumbent Porras. The smear campaign primarily entailed unproven and politically motivated allegations of corruption.

@RepMcCaul @Jim_Jordan @SenTedCruz @RepGregoryMeeks @BobMenendezNJ @marcorubio @SenMikeLee @SenatorLankford @RandPaul @Jim_Jordan @RepScottPerry @SaraCarterDC @JasonPoblete @JudicialWatch @Heritage @OANN @newsmax @thehill @ObserveImpunity @FoxNews pic.twitter.com/NODDJBUVCB

— Liga ProPatria (@LigaProPatria) February 21, 2022

The Foreign Affairs Ministry (MINEX) is aware of the intervention from G13 countries. On January 13, MINEX released an announcement on Twitter that demanded diplomats not intervene in local affairs.

— MINEX Guatemala 🇬🇹 (@MinexGt) February 16, 2022

This is not the only time MINEX has addressed the issue. On January 22, the institution expressed its concerns with the G13 presidency under Swedish Ambassador Hans Magnusson. The Swedish diplomat offered cooperation to the autonomous PC and proposed a private gathering with PC members on January 25.

After the invitation went viral on social media, the Swedish embassy canceled the meeting. Consequently, the G13 indicated on social media it would communicate with the Foreign Affairs Ministry to avoid misunderstandings. The Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations requires foreign embassies to conduct official business through the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

— Suecia en Guatemala (@SwedeninGT) January 26, 2022

The DOS has already sanctioned Porras under the US Northern Triangle Enhanced Engagement Act, commonly known as the Engel List. DOS accused Porras of undermining democratic processes without citing any firm basis or offering her an opportunity to defend herself. The most DOS said was that it was aware of credible information from “media reporting and other sources.”

Several top DOS officials attacked Porras for firing Juan Francisco Sandoval, the chief of the Special Prosecutor’s Office against Impunity (FECI). The Engel sanction was an overt response to Porras’s firing of Sandoval, whom the DOS had honored as an “anti-corruption champion.” Local media, however, had earlier reported that various parties, including Guatemala’s former first lady, had filed 47 complaints against Sandoval.

González told the Impunity Observer: “the DOS placed Porras on the Engel list to defame her, to further politicize Guatemala’s justice system, and to intimidate the commissioners and president not to reappoint Porras.”

In 2020, the UN Development Program (UNDP) announced the suspension of the “strengthening capacities of the MP in the fight against impunity” program due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in February 2022, the UNDP announced the continuity of the suspension due to an alleged lack of commitment from the MP toward addressing legal impunity.

The UNDP’s announcement during the nomination process adds to the perception of intimidation against the commissioners and President Alejandro Giammattei. This is especially the case as Porras’s presence on the final list of six remains pending.

Multiple expert sources—who must remain anonymous given legitimate fears of reprisal—have shared: “As a result of the negative public reaction to the ambassador’s meeting with judges, the DOS is using USAID and its affiliated NGOs as their spearhead to influence the MP appointment.” USAID Administrator Samantha Power’s statement that Porras “uses her office to intimidate and persecute judges and prosecutors standing up for the rule of law” coincides with the sources’ information.

One of our sources asserted that “The Rafael Landívar University rector has signaled to the commissioners that the US embassy will place on the Engel list those who do not vote for embassy-approved candidates and against Porras.”

Several sources have indicated that prosecutors are now hesitant to do their duty because Sandoval told them to wait until May. This is consistent with DOS support for Sandoval, and it coincides with DOS efforts to control who is appointed as the next prosecutor general.

Troll Centers Undermine Porras

Social media has become the primary tool to shape public opinion and a means for citizens to express themselves. The influence of troll accounts has a significant impact on the topics discussed in Guatemala. NGOs such as United Against Corruption (UAC) use troll centers to promote specific political agendas.

“Since the beginning of 2022, Guatemalans on social media have focused on the coming political events. One of the trending topics is the appointment of the prosecutor general,” Luis Fernando Urbina, a Guatemalan social media analyst, told the Impunity Observer.

In January, the first trending topic regarding the prosecutor-general election was the appointment of someone to the PC. The subject was former Commissioner David Gaitán of the UN-created International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). He garnered the position given his current status as the dean of the Da Vinci University law school in Guatemala City. This trending debate lasted for over a week. In early February, the main topic was current MP Chief Consuelo Porras. Online trolls accused her of being compromised.

The troll accounts tend to repeat the same messages almost identically and retweet each other’s content. For example, Twitter handle @PabloCa27615484 has 2,667 followers and was created in 2019 but has had only one original tweet since its creation. Every other post is either a retweet or a reply. According to Urbina, “These accounts serve as a sounding board for other accounts with larger reaches and audiences.”

UAC and the Quetzaltenango Citizen Collective are other likely troll accounts. There is no way to verify their authenticity, and their websites either do not exist or have been inactive for years. However, they have prominent followers such as Stephen McFarland, a former US ambassador to Guatemala; the Winaq Party, a Guatemalan progressive party; Iván Velásquez, a former CICIG commissioner; Amilcar Pop, a leftist congressman; and an assortment of journalists.

According to a seven-day analysis by Urbina, with social-listening tools, of the prosecutor general trending on Twitter, there were 1,502 original tweets from real people, dwarfed by 18,393 retweets. Urbina told the Impunity Observer, “There is a palpable, coordinated effort in the creation of new self-proclaimed independent media that focuses on creating and spreading news related to the prosecutor general, corruption cases, and alleged social organizations.”

Echoes of the Past

The DOS has openly had an active role in Guatemala’s justice system over the last decade. More specifically, González claims “the DOS has had plenty of involvement with the selection of the prosecutor general since 2010.”

“In 2010, US Ambassador Stephen McFarland and CICIG Commissioner Carlos Castresana illegally pressured Constitutional Court (CC) magistrates to remove the newly appointed prosecutor general to make way for their candidate. The CC annulled the process and began it anew, adding Claudia Paz y Paz, who was later appointed.” A report published by the American University Center of Latin American and Latino Studies—in Washington, DC—praised Castresana, a Spaniard, for playing a major role in the dismissal of an “unscrupulous prosecutor general,” which paved the way for Paz y Paz’s appointment.

In 2014, Hillary Clinton called former Guatemalan president Otto Pérez and insisted he pressure the PC to nominate Paz y Paz. Despite this, the PC did not include Paz y Paz on the list of six. Pérez appointed Thelma Aldana to succeed Paz y Paz.

The CICIG had called Aldana corrupt when she was a candidate for Supreme Court magistrate in 2010. However, it remained silent in 2014 when Aldana was appointed as prosecutor general. She aligned herself with the DOS, including cooperating to remove Pérez from the presidency and put him in jail. It took six and a half years for Perez’s trial to begin.

A year after Aldana’s term ended, the MP filed charges against her for embezzlement in a building purchase. The Finance Ministry valued the building at one-half the price Aldana paid. The building did not meet legal standards for government purchase.

In February 2020, Aldana fled to the United States, and former Representative Eliot Engel enthusiastically endorsed her asylum request. She was hailed at the White House by Kamala Harris as a fighter for justice.

Irregularities in the current prosecutor-general appointment process demonstrate a will to override the Guatemalan Constitution. Inconsistencies between the constitution and application of the PC Law appear to be undermining the selection process. Illegitimate tools such as social-media trolls are discrediting current authorities and making it more difficult for them to do their jobs. Various foreign and local parties are acting illegally and manipulating the prosecutor-general appointment away from the rule of law.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.