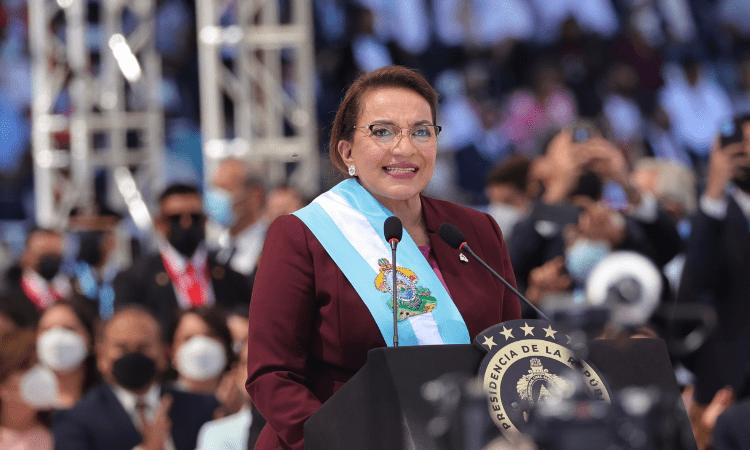

On February 17, 2022, Honduran President Xiomara Castro requested UN support in creating the International Commission against Impunity in Honduras (CICIH). For Castro, corruption and impunity “are two scourges that have vastly damaged the country.”

The United Nations agreed and announced a mission trip on May 9 to Honduras. US Democrat Senators Tim Kaine and Patrick Leahy showed interest and sent a letter to the US State Department (DOS) asking to collaborate with them. Kaine and Leahy argued that the CICIH could contribute to corruption and impunity eradication in Honduras.

The CICIH, however, will not be the first of its kind in the region. In 2007, Guatemala established, also with UN cooperation, a CICIH equivalent: the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). From 2016 to 2020, Honduras also hosted a commission led by the Organization of American States. These two experiences offer clues regarding the potential outcomes from a UN-led initiative in Honduras.

The Creation of CICIH

Castro included the creation of the CICIH in her campaign platform. During the 2021 electoral period, she shared her plans to work with the United Nations to fight corruption.

On April 11, Edmundo Orellana, the Honduran anti-corruption secretary under Castro, announced that a dialogue with the United Nations and Honduran officials would start in May. The first topics for discussion will be CICIH responsibilities and the length of its tenure.

The Castro administration expects the CICIH tenure to last longer than the four-year presidential term. For Orellana, “setting Honduras’s justice system on track” will require more time.

In addition to those matters, the UN mission will meet with Public Ministry (MP) officials and choose the future CICIH members, who the United Nations claims will be carefully selected leaders. For Foreign Affairs Minister Enrique Reina, “this upcoming meeting shows a true effort by the United Nations to fight against corruption in the country.”

Corruption in Honduras

Honduras is passing through a critical period regarding corruption. With 23 points out of 100 in 2021, the country got its lowest score ever on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. El Salvador and Guatemala outperform Honduras with 34 and 25 points, respectively. However, with 20 points for a flagrant dictatorship, Nicaragua had the poorest performance of all neighboring nations.

In February 2022, the United States accused former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández of drug trafficking and requested his extradition to US courts. In the meantime, his brother Antonio Hernández is serving life imprisonment in the United States due to a drug-trafficking conviction.

Previous Attempts to Fight Corruption

In January 2016, then President Hernández signed a cooperation agreement with the Organization of American States (OAS) to create the Support Mission against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH). MACCIH’s goals were:

- to support and collaborate with the Honduran state to sanction and investigate corruption;

- to contribute to the communication between state anti-corruption institutions;

- to propose new laws and law reforms to strengthen the fight against impunity;

- to help invigorate the accountability system in Honduras.

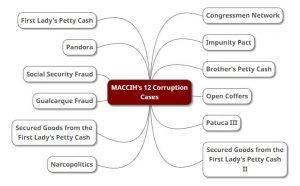

MACCIH investigated 12 corruption cases involving former politicians, government officials, and incumbent congressmen. Accusations included public-funds embezzlement, money laundering, and accepting bribes.

One of the cases was the Congressmen Network, in which a group of legislators allegedly diverted over $300,000 of public funds allocated for NGOs. Augusto Cruz, Enrique Padilla, and Audelia Rodríguez—from the political party VAMOS, Dennys Sánchez from the Liberal Party, and Eleázar Juárez from LIBRE were among the accused. The latter is Castro’s party.

Other cases that involved congressmen were the Impunity Pact, Pandora, and Open Coffers. MACCIH became a threat to them, and in December 2019, Congress suggested the government terminate MACCIH’s mandate due to “power abuse and lack of constitutional guarantees.”

Subsequently, the Hernández administration announced the MACCIH would cease to exist in Honduras from January 2020. The OAS said it could not reach an agreement to continue cooperating with the Honduran government.

Comunicado Oficial. pic.twitter.com/T6ao8i1cZY

— Cancillería Honduras (@CancilleriaHN) January 17, 2020

The Guatemalan Experience

In 2006, then Guatemalan President Óscar Berger and the United Nations signed a cooperation agreement to “combat any manifestation of illegal and clandestine security forces operating in the country.” One year later, they created the CICIG.

According to the CICIG mandate, it was a fully autonomous institution operating under the country’s legislation. Of the cases pursued by the CICIG, however, the responsibility to prosecute them exclusively lay in the Guatemalan justice system.

The United Nations and its General Secretariat appointed CICIG commissioners, who enjoyed diplomatic immunity. However, corruption scandals have tarnished the United Nations’ reputation in recent years. For instance, in 2015 US officials arrested former UN General Assembly President John Ashe, since he accepted bribes from Chinese businessmen.

Other cases that question UN integrity include money laundering and turning a blind eye toward the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis. This, together with reported due-process violations in CICIG investigations, has led to the widespread belief that Guatemala lost its sovereignty to the United Nations, the CICIG, and the DOS—the largest CICIG contributor.

The predicament for host countries is that they are inviting in a new power center and potential source of additional corruption and abuse. Diplomatic immunity meant CICIG officials did not fear consequences when making accusations. Honduras risks succumbing to the same problem.

After a decade of CICIG operation, former President Jimmy Morales did not renew the CICIG’s mandate. The commission left Guatemala in September 2019 with a divided public opinion on its performance.

By April 2019, a Prensa Libre survey revealed that seven out of 10 Guatemalans approved of its work. According to political analyst and historian José Calderón, the CICIG helped reveal the current infiltration of corruption and organized crime inside the Guatemalan state.

While corruption refers to illegal activities, impunity means freedom from punishment. Despite the CICIG’s attempt to eradicate impunity in Guatemala, civil-society organization Liga Pro Patria and former Supreme Court Magistrate José Quesada believe the CICIG misused its power. For them, the CICIG had a leftist bias that undermined the country’s institutions.

In its latest report, the Liga asserted the CICIG became what it was supposed to remove. This report documents US officials meddling in local affairs, the politicization of local justice, and the contradictions between the CICIG and the Guatemalan Constitution.

The Impunity Observer has previously reported DOS interference in CICIG operations. Quesada publicly accused CICIG Commissioners Carlos Castresana and Iván Velásquez of manipulating witnesses, abusing preventive prison, and ideologically tilting justice in Guatemala.

Further, Guatemalan justice officials apprehended former CICIG member Leysi Santizo in February 2022 due to alleged obstruction of justice. More CICIG members and allies are under investigation.

Outcomes from MACCIH and CICIG

According to the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, Guatemala and Honduras have not improved judicial performance during the anti-corruption commissions’ tenures. The index, launched in 2015, measures the absence of corruption, constraints on government powers, civil and criminal justice, and law enforcement.

With a steady score of 0.44 out of 1 in 2019, Guatemala showed no improvement in its rule of law. In the case of Honduras, when the government created the MACCIH in 2016, the index scored the country 0.42 out of 1. As of 2020, when the MACCIH left, the score dropped to 0.40.

Both CICIG and MACCIH failed to generate a positive long-term impact on the countries’ judicial systems. These previous cases inevitably lead to questioning the effectiveness of what will be the outcomes of the new commission to fight against impunity in Honduras.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.