Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro has revived a centuries-old territorial dispute as a smokescreen before the 2024 presidential election. The conflict with Guyana doubles as a strategy to corner the Joe Biden administration. The Chavista regime intends to stay in power well beyond 2024; it also expects the Biden administration to eliminate all sanctions on Venezuela’s oil, gas, and mining sectors.

On December 3, 2023, the Chavista regime held a referendum to ask citizens for support in the annexation of the Essequibo region in Guyana. This represents around two-thirds of Guyanese territory and an even higher proportion of its precious natural resources, notably those in the Atlantic Ocean. According to Chavista officials, all five referendum questions received more than 95 percent “yes” votes, portraying alleged citizen support.

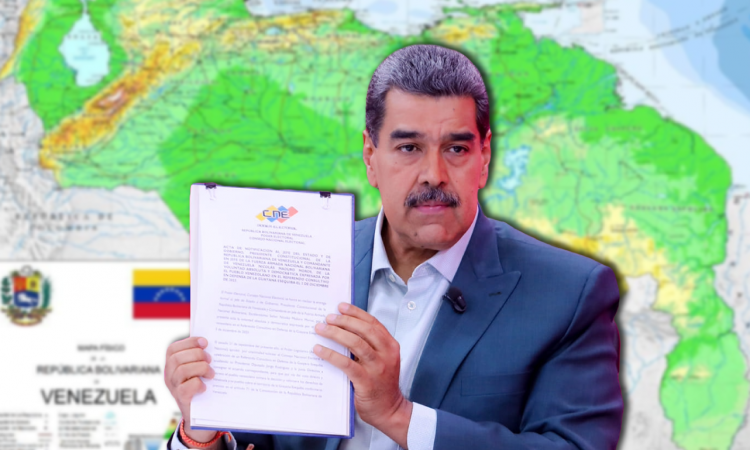

Ordené de manera inmediata publicar y a llevar a todas las escuelas, liceos, Consejos Comunales, establecimientos públicos, universidades y en todos los hogares del país el nuevo Mapa de Venezuela con nuestra Guayana Esequiba. ¡Este es nuestro mapa amado! pic.twitter.com/qliW31Lyb9

— Nicolás Maduro (@NicolasMaduro) December 6, 2023

After election day, however, the regime appeared to be on a practice run for electoral fraud next year and provided unclear electoral data. Elvis Amoroso, head of the electoral authority, claimed the referendum had a “historic turnout” of 10.5 million voters. A day later he stated that the referendum had “10.4 million votes.” Given five questions in the referendum (five votes per voter), it remained unclear whether Amoroso was referring to total votes or voters. He later clarified that he was referring to voters, but as of this writing—three weeks after the referendum—the electoral authority has not published official results.

Citizen support for the referendum is mere propaganda for the shameless and brutal Chavista regime, and local journalists reported few people showing up to participate. Nevertheless, the referendum has failed to achieve the regime’s purpose of gaining at least a modicum of popularity. Venezuelans reject the dictatorship while they also, in general, support Essequibo annexation.

According to the December survey by pollster Power and Strategy, Maduro would get 21 percent of the votes in 2024 if he were to face opposition leader María Corina Machado, who would get 73 percent. On October 22, Machado got 92 percent of the votes in the opposition primary election, in which over 2.5 million Venezuelans voted. However, Amoroso knows who butters his bread, so he swiftly banned Machado from participating in the upcoming election. If that ruling stands, the 2024 election will have zero credibility.

With the Essequibo referendum, the Chavista dictatorship is also testing the international community’s tolerance before the 2024 election. For instance, the regime allowed neither local nor foreign observers to oversee this electoral process, which was a façade.

In addition to testing the international community’s tolerance, the socialists are playing games with the US government, which has an ever weakening reputation as an opponent of dictatorships. On December 20, the Biden administration released Alex Saab—Maduro’s right-hand man whom the US government accused of money laundering and bribes. In exchange for Saab’s freedom, the regime released 10 US prisoners in Venezuela. Saab also cooperated with US Drug Enforcement Agency officials for a year.

Some quick thoughts on the second and third order geopolitical effects of the release of Alex Saab.

Ukraine, Israel, Guyana, and Ecuador/Colombia need to watch out.

But first here you can see the Heroes welcome he just received in Venezuela. 🧵 1/9 pic.twitter.com/ydzC36EwJ3

— Joseph M. Humire (@jmhumire) December 21, 2023

In October, the Biden administration eased sanctions on Venezuelan oil, gas, and mining industries. The US government had one condition: the regime had to negotiate with the opposition to guarantee free and fair general elections—as if that were going to happen. Easing the sanctions after such elections might make sense, but not before. In 2022, the Biden administration also released two of Maduro’s nephews, whom the United States accused of narcotrafficking. The US government seems to be befriending its enemies while treating its allies, such as Guatemala, with contempt.

By threatening neighboring Guyana with annexation of most of its territory, the dictatorship has more power to negotiate for the elimination of US sanctions against Venezuela. An armed conflict would have devastating effects on the region and the world’s energy supplies. The United States would also struggle to address a military conflict in South America, since it is occupied with Ukraine, Israel, and the Houthi attack on commercial ships in the Red Sea.

In the past eight years, Guyana—with the help of US oil companies—has discovered new oil, gas, and mining deposits in Essequibo. This has led to unprecedented Guyanese economic growth. According to the World Bank, in 2022 Guyana’s GDP grew by 57.8 percent in comparison to the previous year. This was the highest GDP growth in the world in 2022. While US oil company ExxonMobil in Guyana is producing 400,000 barrels per day, a Bloomberg report estimates that it could reach 750,000 by 2026. For comparison, Venezuelan state-owned oil company PDVSA produces 810,000 barrels per day.

The Chavista regime sees Essequibo as tempting booty. However, Venezuelan political analyst Esteban Hernández of Contra Poder told the Impunity Observer that the regime is poorly prepared for such a war despite the enemy’s small size and scant military power. The Venezuelan armed forces lack funding, training, and logistics. For Hernández, the armed forces can face unarmed citizens but not an opposition army. Further, Maduro cannot ruffle the feathers of high-ranking military officials, since they keep the dictatorship in power.

The Essequibo territorial dispute is for Maduro a tool, a power play to circumvent the 2024 general elections. He is aware that free and fair elections would end his reign. He and his partners would then likely face justice for their crimes committed. Maduro has little choice then but to commit electoral fraud or go to war. The latter appears to be his last resort, another trick up his sleeve. Although unlikely, a cornered, desperate regime could take its lackluster military to war—for regime continuity as much as for loot.

This article reflects the views of the author and not necessarily the views of the Impunity Observer.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.