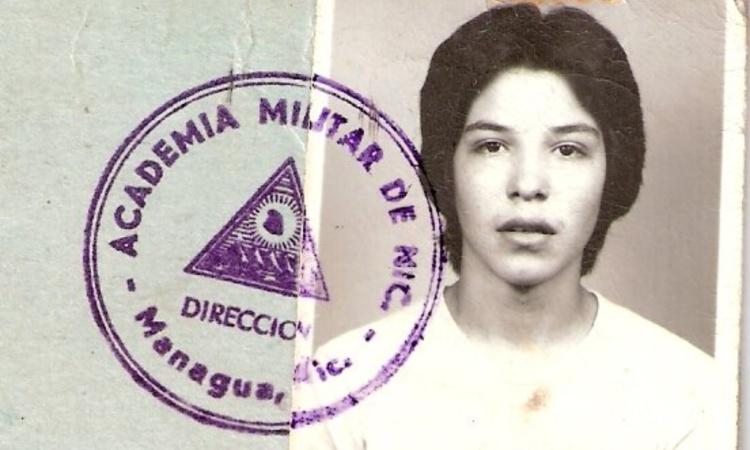

I was born in Nicaragua, a country with a history of violence and insurrection. Nicaragua was in a state of civil war when my parents shipped me to Montreal in 1979, a move that effectively saved my life. The previous winter, my mother had sent me to stay with friends in Guatemala City, waiting out the violent outburst that the assault on the Legislative Assembly in Managua had brought the previous September of 1978.

I returned to Grade 11 in February, only to be told that I would be leaving again soon. I was not pleased to leave behind my native land, my track and field training, my friends, and my family. I was an adolescent boy with Marxist sympathies. My maternal grandfather, who was a conservative, had given me materials to read from an early age that indisposed me to the Anastasio Somoza regime. Ironically, that same grandfather was married to a distant member of the Somoza family, my grandmother.

As an adolescent, my sympathies lay with the communist Sandinista guerrillas, not with the conservatives, and my parents feared that I would take to the mountains to join the guerrillas. At the time, several youths no older than I was, some of whom we knew, had done just that and perished during the first wave of armed insurgence in the fall of 1978. I felt that I was forced to leave.

I arrived in Canada in the spring of 1979. I first came on a student visa to improve my English skills while waiting for the Soviet- and Cuban-backed communist armed insurrection to dissipate. Nicaragua was a pawn in the Cold War, heating up with the challenges that Ronald Reagan brought to the Soviets. Not many among my parents’ generation could conceive at the time that the communist guerrilla youth calling themselves Sandinistas would overthrow the government. They took their name after the bandit revolutionary Augusto Sandino, who roamed the northern hills of Nicaragua, the Segovias, in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

My grandfather Navarro, and later my father, had built and developed a ranch and coffee plantation, La Parranda, just inside the department of Jinotega, north of the city of Matagalpa, where I was born. Some of the founders and later the high command of the Sandinista guerrillas were also from Matagalpa. As part of the same generation, my parents knew Tomás Borge since childhood. He became the cofounder of the Sandinista National Liberation Front. My parents also knew of the younger Carlos Fonseca, another one of the FSLN originals. Dora María Tellez went to school with my older sister. She was a prominent Sandinista guerrilla who in later life became a dissident and is now under regime persecution.

In July 1979, the guerrillas won, and soon they came for my grandfather, my father, and most of their friends. My father had been a Somoza partisan and served as mayor of Matagalpa in the late 1960s, a decade prior to the revolution. My parents were expropriated; my father was thrown in prison; and several members of our family were persecuted, imprisoned, tortured. Some were executed. Most notably, my uncle Julio Fonseca, who was at the time commander of a garrison on the Atlantic coast, was pushed alive out of a Sandinista helicopter. He was married to my aunt Amelia, my father’s sister, whom Tomás Borge had unsuccessfully pursued in their adolescence.

My naïve enthusiasm for socialist revolution stopped with the many abuses, human-rights violations, and killings at the hands of the purportedly liberating guerrillas. Many and worse atrocities than those the people had fought to free themselves from returned. Revenge is not justice. Killings and abuses are killings and abuses regardless of who carries them out. I understood that quickly.

Soon, the Sandinistas turned the country into a slightly milder version of Cuba. Neighborhoods were organized with eavesdropping structures that spied on the neighbors and controlled food-rationing cards. The revolutionaries nationalized industries and farming, set up unproductive cooperatives, and distributed the country’s wealth among themselves. Political liberties and freedoms were only afforded to those who propagated Sandinista politics; secret police trained by the East German Stasi were put in place; and Nicaragua raised the largest army in the region and the largest army in the hemisphere in relation to its population. Nicaragua turned into a Soviet military base.

Their economic policies were abominable. The government began printing currency and soon crashed the national economy, pushing it into an inflationary spin that devalued the currency 10,000 to one. Nicaragua was once the food basket and economic dynamo of Central America. It quickly became plagued with shortages of basic foodstuffs. This hard reality observed from Canada, where I had become a child political refugee, purged me of the Marxist sympathies of my youth. It did not stop naïve Canadians from expressing admiration for my birthplace at the time. Many an enthusiastic but naïve soul lectured me with gusto about the creation of a New Man in Nicaragua. We often hear how young Canadians go to university to lose their faith and to become Marxists. I regained my faith and shed my Marxism during my undergraduate years.

Canada, Then and Now

I ended up in Canada, somewhat by chance. The choice of Canada was made for me way back in 1967. My parents had visited Montreal during Expo 67 and loved the city. My mother then decided that my older sister would come to study in Montreal, so she sent her to Loyola College (now Concordia University) in 1974–75. When my parents rushed me out of the country in 1979, I came to stay with my twenty-something student sister.

I was not fully aware of what it meant to be in Canada, but I did part of my growing up in a political household, so I was politically alert as an adolescent. The full import of being in Canada did not dawn on me until the communist Sandinistas took over in July 1979.

As a young adolescent, I did not have formed expectations of Canada, but I could grasp the value of a peaceful society in light of what I had left behind. Over the years, however, I learned to appreciate the common law tradition and the values of the Westminster system of government. The rule of law, in my view, is the most important aspect of that inheritance received from Britain.

The first shocking surprise about the nature of power in Canada was brushing against the Quebec government of the Parti Quebecois. They prevented me from registering in the Jesuit high school just a few blocks from where my sister lived and across the street from where she went to university. I was forced to go to a French-speaking school, which was not a tragedy for me because my ancestors on the Génie side seem to have been Dutch-loyalist Walloons who migrated to the Caribbean, to the Dutch Antilles, shortly after Belgium broke away from the Dutch crown. I fully expected to learn the language of some of my ancestors while in Montreal, but the legislation forcing me and all others in my “category” of people left a bad taste in my mouth. I finished high school in French, and when I had to go to CEGEP, I willingly chose to continue in French. I love the French language. I enjoy speaking, writing, and reading in French, but I never forgot that experience of being compelled by government in such a way in a free, democratic state.

Canada has changed immensely since I arrived. Forty years ago, politicians would resign in shame for violating rules, breaking laws, violating parliamentary ethics, reneging on promises, or being caught telling untruths. These seem like quaint values now. The patriation of the constitution in 1982 made us a more litigant bunch and devalued the unwritten rules in the minds of the electors. We have become less engaged, more aloof, less interested, and less participatory in public affairs. We are more susceptible to fear and uncertainty. The expansion of the welfare state has made us more entitled and more risk-averse. We seem to be more accepting of government intrusion in our lives, we take our liberties and freedoms for granted, and we have become less demanding of quality representation in governments. The Canada of 40 years ago hardly exists.

The Erosion of Canadian Freedoms

There are many government actions and policies that concern me and remind me of the country I left—too many to list, but I will mention a couple. First, I am baffled that Jagmeet Singh, Canada’s current New Democratic Party leader, publicly and openly glorifies the Cuban revolution. The same goes for Prime Minister Trudeau and for his father Pierre. They, like so many others, get trapped in the romanticism of revolutionaries, their lofty pronouncements and their real or imagined concerns for justice, but fail to grasp the bloodletting tactics and their murderous record. They ignore the high toll of suffering inflicted by these people.

The current proposed federal policies designed to exert government control of content on the internet is one of the most outlandish policies I have seen in Canada. Many other policies and actions are serious distortions and erosions of Canada’s traditions of freedom: forcing western farmers to sell their wheat to the government at predetermined prices, violating provincial jurisdictions to impose taxes on entire populations, and persecuting immigrant women through human rights courts for refusing to handle the male genitalia of persons posing as women, burning places of worship with impunity. Ottawa also forces Albertans to send billions of dollars to jurisdictions that actively block the very resources that make the money they covet from us.

However, the most damaging, I fear, have been the policy reactions to COVID-19. To be clear, the imposition of such wide restrictions was always a policy choice that did not need to be made in such depth and scale. Governments have stepped way out of their bounds, violating the most basic liberties, the worst of which was not forcibly interning people on so-called COVID hotels but the blanket restriction on citizens’ abilities to protest the limitations of their rights, which was endorsed by courts in Alberta and in Nova Scotia. Was it about the spread of disease? Other protests such as Black Lives Matter and anti-Israel ones—equally if not more likely to spread the disease—were not deemed a threat to the power of those forcing restrictions and therefore not prosecuted. The ability to oppose and challenge government policy is the oxygen of liberal democracies, and I was baffled to see these limitations exerted and applied nearly uniformly and unquestioned by elected officials, medical bureaucrats, police, and courts in our country.

I would have expected a greater resistance based on conscience at some of these various levels. I am profoundly disappointed in my fellow Canadians, especially in my fellow Albertans, for not resisting these abuses in stern ways. We should have honored better our provincial motto: fortis et liber, strong and free.

I fear that the precedents now set by COVID policies and the indifference to such abuses will leave a lasting tear on the fabric of liberty of this country.

Canada’s Deteriorating Free-Speech Culture

I feel completely free to voice my ideas and opinions in Canada. For more than a decade, I have been working in what some of us call the freedom movement in this country. I have worked in four different freedom-loving institutions in Canada, including one in the Atlantic region. I spent the previous twenty years teaching in a few universities and, ironically, universities were the least free or the most oppressive places that I worked.

My contract was terminated in one private university because I voiced my views about the academic lynching of one of my colleagues in 2009. It is a long story, but a group of disgruntled professors and administrators openly conspired to fire a colleague just because they disliked him and disliked his approach to being an academic. This friend happened to be a socialist, if not a Marxist, like many of those willing to crucify him and end his career. It was disgusting. The dean at the time found a way to cancel my contract after I quietly and privately voiced my opinion about the travesty inflicted on that former colleague. That he was a Marxist did not matter to me. He was—and still is—a real scholar, a good teacher; he loved his students and was a conscientious thinker, always in pursuit of the truth that he saw in the evidence before him. He was not a follower; he thought for himself and was not fond of following fads that he found detrimental to teaching and to student learning.

The behavior among many of my other colleagues was reprehensible, and in retrospect, I am not unhappy to have been pushed out. I recognized the brutish nature of the lynching. I had seen collectivism flexing its muscles and exercising power to impose one way of viewing or doing things, along with the reaction of intellectual mediocrity being challenged by the excellence of one or a few others. This was, and still is, everyday behavior in Sandinista Nicaragua. It was a bad experience, but I am grateful to the dean who liberated me from my colleagues’ midst.

Since then, the situation in universities has deteriorated further: cancel culture has exploded, academic standards have fallen, safe spaces are now created for students protecting them from confronting different views, specific lines of ideological thinking are now imparted and imposed openly, whether environmentalism or the various branches of social justice. The worst of these is the newly emerging imposition of racial thinking.

That said, I am sufficiently optimistic to see that there remain enough germs of liberty in Alberta to strengthen the resolve to turn these trends around. However, it takes a participatory citizenry with the willingness to stand up to the curtailing of their freedoms, the intrusive or expansive designs of government bureaucracies, and well-meaning politicians. Canada remains a decent country in which people can thrive, assuming no more lockdowns, but it can always improve.

What Young Canadians Should Know about Socialism

As a young person who once sympathized with socialist aspirations, I have had the luxury to reflect on some of these things. I have concluded that the promises of socialism are appealing because we all crave justice and equality. What could be bad about them? But, at that age, we rarely think about how we are going to get there and whether it is even possible or desirable. We could all learn from the wisdom of Milton Friedman, the libertarian Nobel-recipient economist, who challenged us to evaluate ideas and policies for their results and not for their intentions.

My direct experience with socialism is limited, but I can draw on the indirect experience from family members in my country of birth. Revolutionary socialism is never as advertised and nor is the so-called progressive kind. My one personal experience with socialism is the effective disappointment that all the good presented as ideas of redistribution and justice resulted in greater abuse and injustice. The Ortega-Murillo family, the ruling family in Nicaragua, are now among the richest people in the country. Daniel Ortega had no formal education and was penniless when he arrived into government with a ragged camouflage uniform, tattered boots, and an AK-47.

Given the average income of one of his countrymen, he would have to live several lifetimes to amass the kind of wealth he now possesses. So, there was redistribution of wealth. He and his close allies retained the properties and assets of those they disposed, and some of it trickled down to the poor. Nicaragua is now poorer than it was before they seized power, and the country now competes with Haiti at times for the spot of poorest in the hemisphere. The country traded oppressors from one colour or ideology for another. Tens of thousands of lives were wasted in a dozen or so years of fratricidal war to make a change that left the country worse off. It is a real tragedy. Change does not always result in better things, as progressives naïvely think.

Four decades later, Nicaragua has become a prison for all those who are not directly profiting from the regime. There is no free press, no freedom of expression, no property rights, scant human rights, no personal safety, and the list goes on. As I write this, since May 2021 the Sandinistas have kidnapped and disappeared over thirty community leaders and potential presidential candidates—not actual candidates yet—who might be a threat in the predetermined “election” that will take place in early November of this year.

The supposedly benevolent Sandinista government that Pierre Trudeau, Joe Clark, Brian Mulroney, and many Canadians naïvely supported has become one of the most hideous political clubs on the planet. The Sandinista brand of socialism became such an embarrassment to the International Socialist movement that three years ago they finally kicked them out of their socialist siblinghood.

The results of Sandinista socialism are appalling and have contributed to immense suffering: people imprisoned and tortured, hundreds of thousands dispossessed and turned into exiled refugees, and tens of thousands of deaths. About 30 percent of those born in Nicaragua living today are in exile. The equivalent in this country’s context would be 11 million Canadians forced to live outside Canada because of political upheaval. This is the legacy of Sandinista socialism, which is still ongoing and has potential to do much worse. I fear that there is more damage ahead as they graft the Ortega-Murillo family as a dictatorship dynasty into the Nicaraguan state.

To repeat: socialism, like all actions and ideas, ought to be judged by the results in the application of the ideas and policies and not exclusively on their stated intentions. This is somewhat captured in the wise popular expression that the road to hell is often paved with good intentions.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.