As law-abiding citizens were celebrating the end of the botched Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), neighboring Salvadorans received the news that their country would host the next globalist experiment: CICIES.

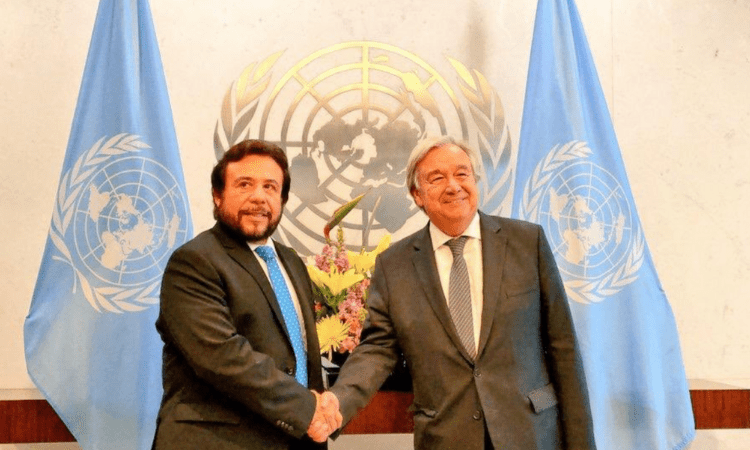

On September 6, President Nayib Bukele and the Organization of American States (OAS) signed an agreement to create the Commission Against Impunity in El Salvador. The CICIES began operations immediately, tasked with “preventing, investigating, and punishing acts of corruption and other related crimes, including crimes related to public finances, illicit enrichment, money laundering, and national and transnational organized crime, in non-limiting terms.”

The OAS, a regional body made up of the continent’s 35 independent nations, claims the CICIES will work within the country’s existing legal framework and be “independent, neutral, and transparent.” However, placing an unaccountable foreign team within the executive branch generates an ominous risk to the rule of law. The CICIES will even get a new police unit within the Salvadoran police to assist with its cases.

Bukele felt inspired by Guatemala’s CICIG, which ended up becoming the very kind of outlaw group it was intended to fight. Even worse, he has requested the CICIG’s failed orchestrator to back the new commission in El Salvador. The United Nations has already confirmed its support and will send staff to the country shortly.

If Guatemala is any indication of the future, the CICIES will be another unnecessary violation of sovereignty and the rule of law under the guise of combating corruption. It has already started off on the wrong foot by not revealing the full scope of its powers, prompting criticism among Salvadoran civil society.

Eduardo Escobar, executive director of local civil-rights advocates Citizen Action, says the roles of the OAS and the United Nations remain unclear. In his opinion, that shows Bukele has not been transparent enough for an initiative of this magnitude.

Javier Castro, director of Legal Studies at FUSADES, a liberal think tank, concurs. He points to a lack of clarity over how exactly the CICIES will pursue its mandate and how it will remain independent from whomever is president and other political actors.

A Fox Guarding the Hen House

At least on paper with the current agreement, the CICIES has limited powers because the president cannot unilaterally grant it jurisdiction over the legislature, the courts, or local governments. A major difference with Guatemala’s defunct commission is that it can investigate wrongdoings only within the 105 institutions that make up the executive branch—for now.

The deal signed last week, however, leaves the door open to a broader mandate. In three months, the OAS and El Salvador will finalize the agreement, which could expand the entity’s powers. For instance, like the CICIG, it could work with prosecutors to indict and jail Salvadoran citizens. That would open a can of worms that could easily lead to politically driven persecution, as was the case in Guatemala.

Short of a constitutional amendment, this power would also be illegal. The Salvadoran Constitution states criminal prosecution is the exclusive domain of the Public Prosecutor’s Office with the support of the National Police. The country’s attorney general has publicly driven this point home.

Furthermore, the agreement fails to mention the need to limit CICIES’s powers or demand accountability from it. Checks and balances are the backbone of democratic institutions; no president, congressman, or judge should have unrestrained authority. This is valid for foreign investigators who land on a sovereign nation with the power to place people behind bars.

Any extended CICIES powers need the approval of the country’s National Assembly. Legislators should think twice before allowing an unelected and unaccountable international commission to subvert domestic institutions.

Even if the CICIES remains in its current form, there is a conundrum regarding its autonomy. If the president controls it there’s no purpose to the commission because he can already investigate all his subordinates and recommend charges to the attorney general. If the commission can decide on its own what to investigate and has the ability to make public statements, then it’s a competing power. The CICIES could say the president or any official has committed crimes, even if untrue, which would give it the power of intimidation: you do this, or we burn you publicly.

Why would any government give this much power to a foreign body?

We Have Seen This Before

Guatemala did not heed the warning of law scholars and civil-society leaders when the CICIG was created in 2006. The mandate got the approval of Congress and the highest court. As a result, 12 years later the country almost went the way of Nicaragua, under the domination of socialists. In the last presidential election the CICIG cleared the way for candidates backed by successors of Marxist guerrillas, and the OAS has similarly leftist inclinations. Thankfully, the Guatemalan people woke up to the threat and defeated the socialist candidate.

The CICIG was a flawed plan to tackle corruption from the beginning. As time passed, its officials began pressuring Guatemala’s authorities into appointing allies to key posts in the Justice Ministry and in top courts. Anyone who stood in the CICIG’s way of power accumulation was at risk, due process be damned.

The CICIG gave free rein to its worst impulses since it knew it was out of reach of law enforcement, thanks to its UN-backed diplomatic immunity. As part of the OAS, the CICIES and its officials will likewise be granted similar privileges, rendering prosecution for eventual crimes virtually impossible.

Any institution with diplomatic immunity that reports to nobody is not consistent with the democratic principle of separation of powers and oversight. This applies throughout the world. It is open to corruption and being co-opted by political actors, of whatever ideology or agenda.

Rather than an inspiration of a neutral, independent, and transparent fight against impunity, the CICIG became an all-powerful body that persecuted political adversaries and undermined Guatemala’s institutions. El Salvador would make a mistake to trust the CICIES to abide by its mandate.

The OAS has history in Mexico the Salvadorans should also consider. In 2014, forty-three Ayotzinapa students in Iguala, Guerrero state, disappeared. The Mexican government asked the OAS for help. The OAS sent a group of experts to investigate.

The group included two former prosecutors, Claudia Paz y Paz of Guatemala and Angela Buitrago of Colombia. They both had a history of political prosecutions favoring a socialist agenda. It was no surprise when the group pointed toward the Mexican army as the culprit for the massacre of the students. After paying the OAS $2 million, the Mexican government did not renew the contract.

El Salvador is right to worry about corruption. Two of Bukele’s predecessors engaged in embezzlement and money laundering; one is in jail and the other is hiding in Nicaragua under the protection of the Ortega regime. However, Salvadorans need to understand only they can hold their own officials accountable. They cannot relieve themselves of this responsibility by bringing in foreigners. Better judges, prosecutors, and investigators are needed for sure, and they should get professional training abroad. There is no magic shortcut, no savior who will come and cleanse their country for them.

Over the next months, Salvadorans should demand that their representatives stop Bukele’s dangerous ambitions. If the CICIES follows in the CICIG’s footsteps, as all signs point to, they will get much more than they bargained for.

Maurício Bento contributed to this article.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.