At the end of 1959 Emi went to Washington DC to look in on his parents. They had left Tatica’s place for a small flat in the DC suburb of Arlington, Virginia.

El viejo had taken work as a busboy in a Washington hotel. He earned an immigrant’s wage, and the work was grueling. When a rough supervisor told him to work harder, el viejo gathered up his meager English and said: “You kill people, but you aren’t going to kill me.”

Living in America had turned el viejo into a boy all over again. When he left the hotel one evening, he found that a fresh coat of snow had fallen on the city; his markers were buried, and he completely lost his way.

The night that Emi stayed with his parents, the old man emptied his pockets to bring home a bottle of red wine – a kindness that would live as starkly in the son’s mind as events that were soon to reshape his life.

As much as he had lost and suffered, Riverito thought first of his boys. But “home” was home no more, and Adolfo was in another world thousands of miles away.

In Budapest with the World Federation of Democratic Youth, Adolfo was the senior Cuban in Hungary and Cuba’s de facto ambassador. As an envoy of Cuba’s new order Adolfo traveled the length and breadth of the continent, giving impassioned talks to rapt audiences and bringing them to tears over the miracle of the revolution.

In private he complained about having to twiddle his thumbs as an international bureaucrat while at home the revolution was pushing forward. But in Adolfo’s case ‘home’ was something more than the revolution. It was the big, fat problem he had left behind: his family.

Before Emi’s Washington visit Adolfo had written his parents: “Separated as you are from all you love, I can’t imagine that you’re happy or will be happy. I didn’t agree with your leaving, as you’ll remember. But let’s hope the hard times don’t get you down. . . .”

Adolfo didn’t hesitate to lecture his parents about politics. As he wrote his father in November 1959: “Your work allowed you to get ahead in life and you came to believe that in our society the man who works can advance himself. But it’s not true. You worked a lot but plenty of people worked a lot harder and never got anywhere at all, they never enjoyed anything . . .

“The revolution is preparing a new life where there will be work and a future for all Cubans. It’s clear that the revolution – in the course of cleaning up and changing the whole system of corruption, of treason, of dirty politics, of handing our national treasure to the yanquis and all the other evils we know about – will inevitably visit harm on people who had no role in those past miseries. It’s also clear that as the revolution secures itself, things will ‘take their level’ – not their old level but their new level, a new life for the Cuban people – a life without so much bitterness, without so much suffering, with instead a great concern for all mankind, a life more humane and worthwhile which is what we’re fighting for. In that new life we will have room for everybody . . .”

In another letter to his father, Adolfo wrote: “Emi has started a bourgeois house and carries on with the grey, boring routine of his petty individualism . . . I’ll tell you plainly how proud I am to see you on your feet, ready to work, no matter how humble and exhausting the work may be . . . The important thing is the solidarity, the spiritual closeness that exists between us, and which does not exist between Emi and me.”

Emi, for his part, disliked turning on the revolution and liked even less the idea of turning on his brother. But nature was pressing him to oppose the very things Adolfo revered: the Party, the leader, the unitary state. Like Mario Cavaradossi, the hero of his favorite opera Tosca, Emi felt his ideals pushing him into the fight. So he put aside his druthers and went toward it.

On a beautiful December morning Emi paid a visit to the FBI building and got on a guided tour. At the end of the tour he did not exit with other visitors but waited for someone to ask why he was still there. To the guard who approached him, Emi said in his impeccable English that he would like to speak with an official. He was shown to a cubicle and invited to sit down.

On a beautiful December morning Emi paid a visit to the FBI building and got on a guided tour. At the end of the tour he did not exit with other visitors but waited for someone to ask why he was still there. To the guard who approached him, Emi said in his impeccable English that he would like to speak with an official. He was shown to a cubicle and invited to sit down.

When the official came in, Emi gave his name and took note of the other man’s. He waited for the prompt and said tersely: “I’m a Cuban visiting in Washington. And I’ve come to see you because I’m concerned about what’s going on in my country.”

“Then perhaps you want to see the CIA,” the other man kindly noted. “The FBI doesn’t get involved in matters outside the United States.”

“Thank you, sir. I know that what you say is now true. But it hasn’t always been. My family was close to the center of Cuban politics for many years. My father, who now lives in Arlington, used to be a journalist at Cuba’s Presidential Palace. He often had praise for the Bureau’s agents who were detailed to Havana. So for me this visit to the FBI is a kind of tribute. I feel honored to be here. I didn’t come to say anything specific. And I will not take more of your time. I only wanted to tell you I’m concerned.”

With an operatic gesture all his own, Emi rose to his feet and left.

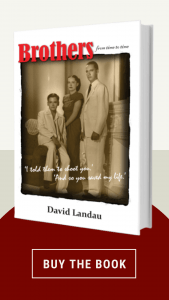

The complete book is being published by Pureplay Press. The book, including all material therein, is copyright © 2020 by David Landau.

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from now through early October, the Impunity Observer will publish excerpts from Landau’s book

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.