Havana, May 1960. Emi got a call from his parents. They were frantic with concern about Adolfo. He had promised to stop over and see them on a visit from Budapest to Cuba; but since receiving that promise they had neither seen nor heard from him. They didn’t know whether he was in Cuba, Hungary, or Siberia. They implored Emi to locate his brother and get news of him.

Like his father Emi was no mean detective. He convinced his enemies, the communists, to disclose Adolfo’s whereabouts. Adolfo was indeed in Havana at a congress of his home organization, which was now called the Rebel Youth. Emi also managed to ferret out Adolfo’s sleeping quarters: the Deauville, a rather swish hotel along Havana’s seaside boulevard or Malecón. Emi got hold of Adolfo and invited him to lunch.

Adolfo was a willing participant but by no means a congenial one. When they met at the Havana Reporters’ Association, itself a death-bound entity, Adolfo began with the words, “Estás sobrealimentado” – You’re overfed.

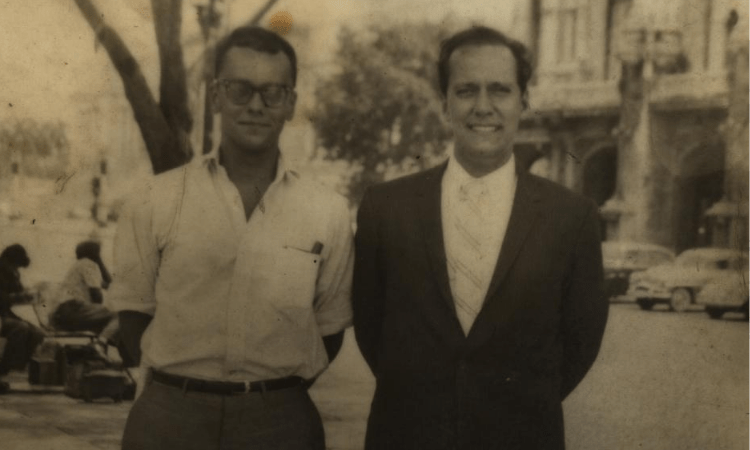

They walked toward the Chinese restaurant Cantón. As meetings between them had become extremely rare, they stopped to have a Polaroid taken by a street photographer. Surely this commission was a nostalgic tribute to el viejo who had begun his phenomenal rise to prominence by snapping portraits of tourists in Havana’s cafés.

In this portrait Adolfo looks the part of the well-to-do tourist that he is – a visitor from Budapest, all smiles, with a boyish nonchalance. Emi produces a smile of sorts but it’s an obvious push; the down-turned corners of his eyes and mouth betray that the meeting is no picnic for him, either.

At the restaurant they went straight to business. Adolfo mentioned the low-cost housing project being organized by comandante Pastora Núñez. Enemies of the government had criticized her for ignoring legal procedures in efforts to speed up construction.

“The important thing is to build the houses,” Adolfo said. “The rest of it can be dealt with in its proper time.”

“I agree,” Emi said. “It’s a good project and needs to be done quickly.”

“How about the other revolutionary measures?” Adolfo asked. “Where do you stand on those?”

‘Revolutionary measures’ was a candy-coated term for confiscations of wealth that the regime had visited on many Cubans and Americans.

“Governments have a right to take properties,” Emi answered, stating the matter without euphemisms. “It’s part of the political contract. I don’t object to that.”

Ever the interrogator, Adolfo pressed in. “Do you accept the leadership of Fidel Castro?”

“I don’t accept the leadership of anyone,” Emi said firmly.

“Fidel is pushing things in the right direction. The country accepts him and so should you.”

“Like everyone else? I don’t think so.”

“Then you’re not being smart about it. You wanted the revolution as much as anyone. It’s your revolution too. Why not find your place in it? But no, that would make you like other people. So you do the contrary and screw up your life!”

“I won’t work with communists. Look Adolfito, it’s nothing to do with you. If you had become a priest I wouldn’t have liked it, but as you’re my brother I would have wanted you to become the Pope. I don’t like your being a communist but since you are one, I want you to reach the highest positions in the Party hierarchy. I want you to succeed.”

“But I don’t want you to succeed!”

“Listen. Los viejos are suffering because of their separation from us. Call them once in a while, would you? Even if the Party is paying your expenses, they must understand you have to talk with your parents.”

“Don’t compare your morals with mine,” Adolfo said roughly.

Lunch was over with an abrazo; they were still brothers, after all. As they hugged, Emi could feel a lot of things in Adolfo’s musculature: the wiriness of a zealot, the buzzing excitement of revolutionary power, the staunchness of the man’s principles, a leanness that came from self-denial, and a warmth which Emi felt to be a strong love for los viejos.

But sentiments made little difference in the oncoming conflict. Cubans were quickly taking sides. Armed groups of veterans from Fidel’s own Rebel Army had started forming units in the countryside, preparing to do to Fidel what Fidel had done to Batista. Emi was already working with one of those groups.

Adolfo, who soon returned to Budapest and without stopping in Washington, likewise knew a bridge had been crossed. Counting the days until he could go home for good, Adolfo busied himself with thoughts of Emi’s likely activity. The contact with his folks that Adolfo had suspended now looked useful to him. In letters from Budapest he flooded his parents with warnings for his brother.

“Tell Emi this is not like the fight against Batista. Castro is much more capable and his popularity is overwhelming. If Emi tries to conspire now, he will not make more of his miraculous escapes. Almost certainly he will be captured and killed.”

In another message: “You must tell Emi not to be so foolish as to play the trumpet in Louis Armstrong’s house.” In yet another, with finality: “Can it be that my brother’s ambition will lead him down the path of treason?”

Emi mulled over his brother’s advice. “Find yourself a place in the revolution!” It was vintage Adolfo, blunt and cogent. All it needed was the right orientation. Emi’s place in the revolution would be against it – and against his brother too.

Resignation

Havana. “El Moro,” the Moor, was one of Emi’s trusted comrades. A strapping Lebanese who bubbled with humor, he was by day an inspector for the Havana bus system and at all times the most reliable of conspirators.

Toward the end of May 1960 the Moor paid Emi a visit. “Doctor, I have a message from Plinio,” he said. “You have to go and see him as soon as possible.”

“Okay,” Emi told the Moor, “I’m leaving immediately.”

After a seven-hour drive to the sanatorium town of Topes de Collantes, and then a climb of several hours through overgrown mountainous terrain which he had to clear with a machete, Emi was in an encampment of men who looked very much like the poster images of Castro’s guerrilla heroes.

Plinio Prieto, a comandante in the anti-Batista war and now a comrade in the anti-Castro resistance, had set up a guerrilla hideout in the Sierra del Escambray, a mountain range in the center of the island. Emi esteemed Plinio highly. Unlike other Cuban fighters, he was cool and methodical. He didn’t exaggerate, he was undemonstrative, and emotions did not color his judgments. His courage was the opposite of bravado. Some called Plinio “cold,” perhaps because his very calmness made them shiver; but in Victor Hugo’s phrase he was hot as fire and cold as ice at the same time.

“Our base is developing,” Plinio told Emi in front of his men. “People are helping us. Many feel betrayed by the revolution. Kids who joined the Rebel Army and went to Havana are coming back with complaints about communist indoctrination and anti-American propaganda. We have men ready to fight. We just don’t have weapons.”

On taking power, Fidel had ordered that all who fought against Batista must surrender their arms to the new regime. “Why should any of us have guns?” he had said in his inaugural talk, pushing out the phrase three times. “¿Armas para qué? ¿Armas para qué? ¿Armas para qué?”

Across the island, men and women of every faction complied – and when they had done so, Fidel’s troops were the only force in Cuba with guns. Anyone else who wanted to start a fight must build up a new supply of arms, which was no easy task.

“We have some guns in Havana,” Emi said, “but only the ones people kept as mementos – not nearly enough to equip a fighting force.”

“We have some guns in Havana,” Emi said, “but only the ones people kept as mementos – not nearly enough to equip a fighting force.”

“Then you have to go abroad, and right away. We need arms for 150 men and we can’t lose time. Carry your short-wave radio. Keep us posted. We’ll do the same.”

Back at home Emi moved quickly and carefully. He wrote cordial letters to his employers – the government regulatory commission which he served as a lawyer, and his alma mater, a top high school called the Vedado Institute, where he now taught English.

Both were official bodies, and Emi had to be delicate. He begged permission to take a short leave of absence in order to explore a job prospect in the United States. Even as he wrote, Cuba’s customary relations with the US were slipping away. So he added a proviso in keeping with the general uncertainty. If he was gone for more than a month, he asked to be considered as having resigned.

To his wife Pelén and her mother Dr. S. – the latter a colleague at Vedado Institute – he gave the same cover story, not wanting to involve them in danger.

Of course he omitted the part about resigning. No matter what the circumstance, a man didn’t resign from his family. His wife and children were tethers that fastened him to the human race. Without them he was an animal.

The complete book is being published by Pureplay Press. The book, including all material therein, is copyright © 2020 by David Landau.

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from now through early October, the Impunity Observer will publish excerpts from Landau’s book

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.