Former Guatemala prosecutor Dennis Herrera has explained to the Impunity Observer in a video interview (parts one and two) why the State Department (DOS) persecuted him, including putting him on the Engel List. Three former Guatemalan officials—prosecutor Juan Francisco Sandoval and judges Erika Aifán and Gloria Porras—committed crimes against Herrera as part of the DOS agenda.

US Ambassador or Proconsul?

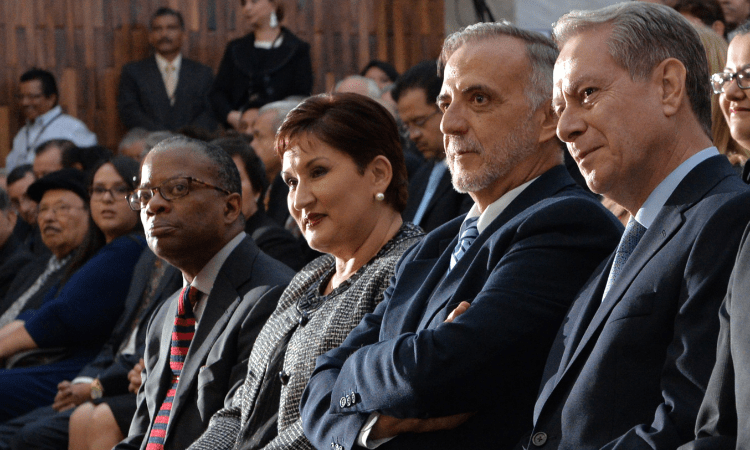

Herrera was a prosecutor from 2004 to 2016. His involvement with the DOS began in 2015 when he was assigned a criminal case against a US bank. Herrera obtained international arrest warrants against the people involved. Summonsed that year by Prosecutor General Thelma Aldana to her office, Herrera was surprised to see then US Ambassador Todd Robinson present.

Aldana harshly criticized Herrera for his actions in front of Robinson. Herrera knew something was wrong because Aldana had authorized his actions. Furthermore, as the prosecutor general knew, the warrants involved several other offices and of course the courts. A month later, Aldana removed Herrera from the case, and he does not believe the arrest warrants were executed.

Robinson illegally intervened in a criminal process and was apparently successful in quashing the case. This is consistent with Robinson’s tenure as ambassador. Questioned by reporters in 2016 whether his actions had violated Guatemalan sovereignty, Robinson famously retorted, “In the list of my concerns, sovereignty comes last.”

You Can Check Out, But You Cannot Leave

After leaving the Prosecutor General Office in 2016, Herrera practiced privately in criminal law. In 2019, Guatemala’s Bar Association elected Herrera to the Nominating Commission for Magistrates.

One of Herrera’s clients, Gustavo Alejos, had been politically influential and had criminal accusations against him. DOS accused Alejos of illegally promoting the appointment of corrupt judges and called its case Parallel Commissions 2020.

Herrera noticed Guatemalan newspapers La Hora and ElPeriódico reporting Sandoval’s accusation that Herrera was an illegal agent working for Alejos. Herrera went to Sandoval’s office and asked to see the case against him. Sandoval said the case was sealed and nobody could have access. Sandoval also contradicted himself and alleged he was not investigating Herrera.

Herrera investigated a car in front of his office, and the police informed him it belonged to Sandoval’s office. Herrera went to the judiciary for an order to force Sandoval to show him the case against him. According to Guatemalan constitutional law, all individuals have a right to see the evidence against them, even if the case is sealed. However, Herrera could not find the case in the normal courts.

The Case That Neither Exists Nor Can Be Viewed

Herrera knew Sandoval had committed illegal acts and that his partner in the DOS agenda was Judge Erika Aifán of the High-Risk Court D. For a case to be assigned to a high-risk court, the prosecutor general must petition the Supreme Court to approve it.

The judiciary assigned Herrera’s request to judge Mynor Moto, who agreed with Herrera that he had a constitutional right to the information against him, if a case existed. Herrera petitioned the prosecutor general and the Supreme Court through judge Moto, and they replied there was no petition or approval to place a case against Herrera in a high-risk court. Moto and Herrera then discovered that Aifán, in complicity with Sandoval, had circumvented the prosecutor general and the Supreme Court to take the case.

Sandoval claimed Aifán was the “natural” judge for the case because she had a group of cases, known as multicausa, from 2016 involving corruption. Sandoval believed Herrera’s case and the Parallel Commissions 2020 case should be part of the multicausa. Former law professor and advisor to the Impunity Observer, José Luis González Dubon says the Constitutional Court (CC) has held that putting these cases together is unconstitutional. González says adding the later Herrera case was also unconstitutional. Aifán had violated the law and committed a felony by taking the Herrera case.

Crossing the CICIG Is Suicide in DOS’s Guatemala

When Moto was acting in Herrera’s case, the Bar Association appointed him to serve the remainder of Bonerge Mejia’s term, a CC magistrate who had died. Moto had not caved to pressure from the UN CICIG commission—an arm of DOS that persecuted its political enemies—in its cases before him. Therefore, DOS wanted to keep Moto off the court.

DOS could count on Gloria Porras, whom Robinson had illegally forced Congress to appoint to the CC in 2016. She dominated the CC, telling fellow magistrates the US ambassador wanted them to vote as she said. Porras committed numerous crimes in executing DOS’s agenda.

Congress swore in Moto as a CC magistrate on Friday, January 29, 2021. Porras refused to seat him, saying there were pending claims against him. That was illegal. She should have seated Moto, and any claims could still proceed.

An hour and a half after Porras denied Moto his seat on the CC, Aifán issued arrest warrants for Herrera and Moto at Sandoval’s request for obstruction of justice. The evidence was their legal efforts to discover if there was a case against Herrera and, if so, in which court.

However, Moto enjoyed immunity as a lower court judge and then as a CC magistrate the moment Congress swore him in. It is illegal for a judge to issue an arrest warrant for any official with immunity. Sandoval and Aifán repeatedly and openly violated the law because they had DOS support and were desperate to keep Moto off the CC.

By Monday, the police were waiting to illegally arrest Moto if he went to the court. He did not and never served as the law required.

An Offer He Did Refuse

Herrera says Sandoval’s brother Ronald visited him at his office and offered to squash his case for $20,000. Herrera refused and filed a criminal complaint with the Prosecutor General’s Office. In 2019, Juan Francisco Sandoval told Herrera he would drop the case against him if Herrera testified against Prosecutor General Consuelo Porras. Herrera said he did not know her and could not follow Sandoval’s script.

DOS subsequently put Herrera on the Engel List in retaliation for not testifying falsely against Porras. The DOS sanctions were for participating in the Parallel Commission 2020 case. This was despite Herrera having not voted for any of the candidates DOS claims his client Alejos was supporting.

Vindication for Moto, Herrera

Pursuant to a CC ruling on a Moto injunction request, a lower court on November 30, annulled all that Aifán had done in the Moto-Herrera case. The court noted that she and the officials involved could be charged with crimes. They are also liable for significant civil penalties for the damage they caused Moto and Herrera. DOS will, as they continuously do with all cases against their agents, call this corrupt. That is despite the clear legal reasoning of the court and the documentary evidence, now public, of the officials’ crimes.

One purpose of the United States-Northern Triangle Enhanced Engagement Act that created the Engel List was the promotion of “transparent, merit-based selection processes for prosecutors and judges.” DOS has violated the will of the US Congress by its illegal intervention against Consuelo Porras’s reappointment, which occurred despite its significant efforts, such as the Herrera-Moto persecution.

Assistant Secretary for Western Hemisphere Brian Nichols stated being on the Engel List stigmatizes the sanctioned individuals. Despite DOS not citing evidence against Herrera, its sanctions resulted in banks closing his accounts and clients dropping him. That makes Nichols’s statement a confession of DOS criminality. DOS is merciless and shameless in imposing its criminal, totalitarian agenda on Guatemala.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

Join us in our mission to foster positive relations between the United States and Latin America through independent journalism.

As we improve our quality and deepen our coverage, we wish to make the Impunity Observer financially sustainable and reader-oriented. In return, we ask that you show your support in the form of subscriptions.

Non-subscribers can read up to six articles per month. Subscribe here.